8. VIII.

TO REESE RIVER.

I leave Virginia for Great Salt Lake City, via the

Reese River Silver Diggings.

There are eight passengers of us inside the coach

—which, by the way, isn't a coach, but a Concord

covered mud wagon.

Among the passengers is a genial man of the name

of Ryder, who has achieved a wide-spread reputation

as a strangler of unpleasant bears in the mountain

fastnesses of California, and who is now an eminent

Reese River miner.

We ride night and day, passing through the land

of the Piute Indians. Reports reach us that fifteen

hundred of these savages are on the Rampage, under

the command of a red usurper named Buffalo-Jim,

who seems to be a sort of Jeff Davis, inasmuch as

he and his followers have seceded from the regular

Piute organization. The seceding savages have

announced that they shall kill and scalp all pale-faces

(which makes our faces pale, I reckon) found loose

in that section. We find the guard doubled at all

the stations where we change horses, and our passengers

nervously examine their pistols and readjust

the long glittering knives in their belts. I feel in my

pockets to see if the key which unlocks the carpetbag

containing my revolvers is all right—for I had

rather brilliantly locked my deadly weapons up in

that article, which was strapped with the other baggage

to the rack behind. The passengers frown on

me for this carelessness, but the kind-hearted Ryder

gives me a small double-barrelled gun, with which I

narrowly escape murdering my beloved friend Hingston

in cold blood. I am not used to guns and things,

and in changing the position of this weapon I pulled

the trigger rather harder than was necessary.

When this wicked rebellion first broke out I was

among the first to stay at home—chiefly because of

my utter ignorance of firearms. I should be valuable

to the Army as a Brigadier-General only so far as

the moral influence of my name went.

However, we pass safely through the land of the

Piutes, unmolested by Buffalo James. This celebrated

savage can read and write, and is quite an orator,

like Metamora, or the last of the Wampanoags. He

went on to Washington a few years ago and called

Mr. Buchanan his Great Father, and the members of

the Cabinet his dear Brothers. They gave him a

great many blankets, and he returned to his beautiful

hunting grounds and went to killing stage-drivers.

He made such a fine impression upon Mr. Buchanan

during his sojourn in Washington that that statesman

gave a young English tourist, who crossed the

plains a few years since, a letter of introduction

to him. The great Indian chief read the

English person's letter with considerable emotion,

and then ordered him scalped, and stole his

trunks.

Mr. Ryder knows me only as “Mr. Brown,” and

he refreshes me during the journey by quotations

from my books and lectures.

“Never seen Ward?” he said.

“Oh no.”

“Ward says he likes little girls, but he likes large

girls just as well. Haw, haw haw! I should like

to see the d—— fool!”

He referred to me.

He even woke me up in the middle of the night

to tell me one of Ward's jokes.

I lecture at Big Creek.

Big Creek is a straggling, wild little village; and

the house in which I had the honor of speaking a

piece had no other floor than the bare earth. The

roof was of sage-brush. At one end of the building

a huge wood fire blazed, which, with half-a-dozen

tallow-candles, afforded all the illumination desired.

The lecturer spoke from behind the drinking bar.

Behind him long rows of decanters glistened; above

him hung pictures of race-horses and prize-fighters;

and beside him, in his shirt-sleeves and wearing a

cheerful smile, stood the bar-keeper. My speeches

at the Bar before this had been of an elegant character,

perhaps, but quite brief. They never extended

beyond “I don't care if I do,” “No sugar in mine,”

and short gems of a like character.

I had a good audience at Big Creek, who seemed

to be pleased, the bar-keeper especially; for at the

close of any “point” that I sought to make, he would

deal the counter a vigorous blow with his fist and

exclaim, “Good boy from the New England States!

listen to William W. Shakspeare!”

Back to Austin. We lose our way, and hitching

our horses to a tree, go in search of some human

beings. The night is very dark. We soon stumble

upon a camp-fire, and an unpleasantly modulated

voice asks us to say our prayers, adding that we are

on the point of going to Glory with our boots on.

I think perhaps there may be some truth in this, as

the mouth of a horse-pistol almost grazes my forehead,

while immediately behind the butt of that

death-dealing weapon I perceive a large man with

black whiskers. Other large men begin to assemble,

also with horse-pistols. Dr. Hingston hastily explains,

while I go back to the carriage to say my prayers,

where there is more room. The men were miners

on a prospecting tour, and as we advanced upon them

without sending them word they took us for highway

obbers.

I must not forget to say that my brave and kind-hearted

friend Ryder of the mail coach, who had so

often alluded to “Ward” in our ride from Virginia

to Austin, was among my hearers at Big Creek. He

had discovered who I was, and informed me that he

had debated whether to wollop me or give me some

rich silver claims.

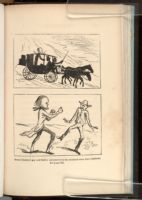

[ILLUSTRATION]

Horace Greeley's gay and festive adventures on the overland route

from California. See pge 156.

[Description: 483EAF. Illustration page. Two cartoon images of Horace Greeley on his California

adventures. The first is Greeley in a stagecoach -- his head is too

big and has broken out of the top. The second is Greeley, again with

an enlarged head, fighting a reluctant Californian.]