Dora Darling the daughter of the regiment |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. | CHAPTER VIII. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 34. |

| 35. |

| 36. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| CHAPTER VIII. Dora Darling | ||

8. CHAPTER VIII.

That night, when all was dark and quiet, both within

and without the house, a slender little figure came gliding

down the stairs and across the kitchen.

With a noiseless hand she slipped back the wooden

bolt, unlatched the heavy door, and crept out into the

starless night.

It was Dora, who, with a little bundle of clothes in her

hand, and her mother's Bible in her bosom, was leaving

behind her the only home she could call her own, and

going out into the wide world to seek a better one.

Her future course remained perfectly undecided, except

that she intended to travel North as fast as possible,

and hoped in some way to find out that aunt Lucy, of

whom she did not even know the full name and place of

abode, but whom she already loved for her mother's sake.

First of all, however, she determined to go and say

good by to the old house where she had been born and

passed her whole life, except these last unhappy days,

and also to her mother's grave.

Walking hastily on, and congratulating herself upon

the darkness, she soon reached the house, which was

stone step of the kitchen door where she and Tom had

been used to sit and eat their supper together, through

all their happy childhood.

“And now he is a rebel, and gone to fight, and perhaps

he will be killed,” thought Dora, sadly. Presently

she took the little Bible from her bosom, and kneeling

upon the old step with it tightly clasped in her hands,

she prayed simply and fervently to the Father of the

fatherless, that he would guard her dear brother, and her

father, and herself from all evil and sin, and that in his

own good time he would bring them all home to live

with the beloved mother who had gone before.

After this, the little girl felt so much happier and

safer, that she was sure there must be angels about her,

sent by her heavenly Father to comfort and sustain her.

“Perhaps mother herself is here,” thought Dora; and

her eager eyes glanced around as if she might really see

that dear face shining upon her out of the darkness.

But such sights are not for mortal eyes, and Dora

herself soon faintly smiled at her own fanciful hope.

After a few moments she arose, and lightly kissing the

closed door of the dear old home, she took up her little

bundle, and went slowly down the path.

Near the barn she almost stumbled over a dark figure

crouching upon the ground.

“Who's that?” cried she, involuntarily.

“Gosh, Missy Dory, be dat you?” exclaimed a well-known

voice, as the figure straightened itself, as far as

was possible.

“Picter! Why, Picter, can it be you?”

“Me mysel', missy, an' proper glad to see lilly missy

agin,” replied the negro, warmly.

“Well, but, Uncle Pic, how came you here, and where

are you going?”

“I's tell you all 'bout it, missy, fas' I can, for 'twon't

do fer me to stay long in dese yer diggins. I's come out

on furlough, as we calls it in de army.”

“O, you're in the army, then?” asked Dora, with a

roguish smile.

“Yes, missy, I is. An' you see we's in camp jes'

now, 'bout fifty mile from here, an' gwine ter stop a spell.

We's moved furder off dan we was when me an' de

captin got back, and so I t'ou't 'fore we moved on agin,

I'd borry a hoss, and come back to de ole place for

sumfin' dat I forgot dat mornin'. An' so yer mammy's

dead, poor lilly missy?”

“Yes, Picter. How did you know?”

“Lor, missy, I's seen some of our folks 'bout here, an'

got all de news. An' I was gwine ter try fer ter see

you 'fore I wented back, 'cause I t'ou't mabbe you wasn'

jist happy down dere, an' I was gwine to see if ole Picter,

that yer mammy gib his freedom to, couldn' do sumfin'

'bout it.”

“I am not living at aunt Wilson's now,” said Dora,

quietly. “I have left there.”

“Lef' dah! An' whar's ye gwine, missy?” asked

Picter, in much astonishment.

“I don't know. Only I am going North, where my

mother's folks live. Perhaps I shall find some of them.”

“Yer pore lilly gal!” exclaimed Pic, with a world of

tender pity in his coarse voice.

“Why don't you come with me, Picter?” asked Dora,

suddenly, as the idea flashed upon her mind. “You

want to go to the North, of course, and very likely, when

I find my aunt, she will take you to live with her, too.

Won't that be nice?”

“But, lilly missy, how's we gwine fer ter find yer

aunty? Do ye know whar she live?”

“No, Picter, nor I don't know her name, except

Lucy; but I guess she lives in Massachusetts. She used

to when mother was married.”

Epictetus pondered the proposition with a gravity

worthy of his namesake. At last he spoke, as one who

has made up his mind:—

“Lilly missy, ter go an' look in a big place, like Masserchusetts,

for a woman named Lucy, 'ould be jis' like

looking in the mowin' for las' year's snow. 'Twouldn't

be no use, no how. But now yer wait a minit, an' I'll

tell yer how we'll fix it.

“Dese yer sojers dat I's wid, come from de Norf,

was to our house dat morning, he's a Masserchusetts man,

an' come down here with one of dere regiments, but

when de oders went home, he stopped, an' has been

fighting 'long o' dese yer fellers.

“Now, missy, yer come 'long back wid me to de

camp, an' I'll take keer on ye dere whiles we stop, an'

w'en dey goes Norf, w'y, we'll go 'long too. What yer

tink o' dat yer for an ole nig's plan, now?”

“That will do, Picter, very well, I should think,” said

Dora, composedly. “When shall we go?”

“Right off, now, lilly missy. 'Twon't do fer dis

chile to be cotched in dese diggins, as I said afore.

Tell trufe, lilly missy, I only come fer de ole stockin'.”

“What old stocking?” asked Dora, wonderingly.

“W'y, missy, de ole feller has been pickin' up de

coppers ebery chance he get, dis many a long year, an'

t'ought one dese yer fine days mabbe mas'r take 'em all

an' gib him his freedom. Den, when mist's say, `Go, ole

Pic,' all to a sudden t'oder day, ebery ting seem turned

upside down, and de silly ole nig scamper off widout so

much as tink 'bout de ole stockin' hangin' up in de barn.”

“And so you came back to get it?” asked Dora, rather

impatiently, for she longed to begin her journey.

“Yis, missy, I's come back fer get it; dat part

my arrant, to be sure. Bud den, 'sides dat, I wanted

know how lilly missy gittin' 'long, an' wedder de coppers

gib me my freedom right out o' han', it 'ould look orful

mean fer me to carry off all de coppers, too, and neber

ax wedder lilly missy could help herse'f some way wid

dem.”

“O, thank you, Uncle Pic,” exclaimed Dora, hastily.

“But of course I would not for the world take one of

them away from you. And how did you know, before

you came, that I was at aunt Wilson's?”

“Lor's, missy, 'twas passed along to me, same as all

de news is.”

“But how, Picter?”

“Well, missy, de col'ud folks dey don't hab no newspapers

nor books, so dey takes a heap o' pains to git de

news roun' by word o' mouf. Dey meets nights, an' dey

tells eberyt'in' dey know, an' dey has ways, missy, heaps

o' ways. Bud now I's all ready for travellin' ef you is.”

“I am in a great hurry to start, Pic.”

“Sho! be you, lilly missy? Den I's mos' afeard you

has'n' be'n ober an' above contented to your aunty's.

Pore lilly lamb. Well, ole Pic's gwine ter see ter ye

now, an' dere shan't nebber no one take ye away from

him without you says so you'se'f. Now I jes' go to de barn

a minit, an' git my lilly bundle, an' den we goes.”

Picter stole cautiously away through the darkness, and

Dora strained her eyes to distinguish once more the dim

outline of her old home vaguely drawn against the gloomy

and a whip-poor-will perched upon the tree that swept

the roof to chant his mournful cry.

Dora shivered nervously, and murmured, “This isn't

home any longer, and aunt's house isn't either. I haven't

any home, now; but the Lord and mother will take care

of me just the same — so I don't care.”

“H'yar we be, missy,” whispered Picter's hoarse voice,

as he rejoined his new charge. “Now we's all ready to

put, I reckon.”

“Do you know the way, Pic, when it's so dark?”

“Neber you fear fer dat, missy. De ole nig fin' he

way 'bout, ef it be darker dan ten black cats shuck up in

one bag. Den, back here a piece I's got a hoss, a fus'

rater, too, dat dey lend me up to de camp. De cap'n

tell 'em trust de ole nig same as dey would hese'f.”

“Do you mean the captain that was at our house?”

asked Dora, who was now tripping along beside the old

negro in the direction of the mountains.

“De berry same, missy. He name Cap'n Windsor —

Charley Windsor. Don' you min' he tole us ter call 'im

Cap'n Karl? Dat de same name as Charley.”

“Yes; and I was real glad afterwards that I didn't

know his true name, for they asked me, you know.”

“No, I didn't know 'bout dat. I heerd dat dey got

wind roun' here dat a Yankee officer got away, an' dey

was rampin' roun' like mad, lookin' fer 'im; an' ole

mas'r was some 'spected, I heerd.”

“Father suspected! Why, he brought Joe Sykes and

some other men to our house to look, and to ask mother

and me questions.”

“Yes, yes, chile, I knows all 'bout dat. Dem fellers is

part ob de Wigilance Committee, an' mas'r had to fotch

'em to he house wedder he like it or not. Den dey tole

him he'd better 'list after mist's died, an' so he did.”

“And did you hear all that before you came back?”

“Not all, missy. I seed a boy las' night, w'en I was

comin' dis way, dat telled me part. He b'longs to one o'

dem Wigilances, an' so heerd de whole story.”

“Poor father!” murmured Dora.

“Well, missy, I reckon he didn' want much drivin' to

go inter de army. He used ter talk 'bout it by spells, an'

say he'd a mind fer ter go.”

“Yes, I know it,” said Dora, sadly.

“Golly! How dark he am here 'mong de hills. Can't

hardly make out de way, now we's lef' de road, but

reckon we's right so fer,” muttered Pic.

“Where are we going first, Picter? Where shall we

find the horse?” asked Dora, a little anxiously.

“Fin' 'im in he paster, missy. I lef' 'im dah as snug

as a bug in a rug, an' de Bible say, `Safe bind, safe find;'

so I boun' him safe 'nouf, I tell ee.”

“O, no, Picter, that isn't in the Bible,” said Dora,

quite scandalized at the idea.

“Ain't it, now, missy? Well, I heern mist's say so

dem's good words, else she wouldn't say dem.”

To this Dora made no reply, and Picter was now too

deeply engrossed in making out their path among the

rocks, fallen trees, hillocks, and ravines of the mountain

side, to continue the conversation.

Nearly an hour had passed, and the little girl was becoming

quite tired, when Picter stopped short at the foot

of a large oak tree, and said, triumphantly, —

“Here we is, Missy Dora.”

“Where? I don't see anything but trees, Picter.”

“No more you wouldn' if 'twas cl'ar as noonday,

honey; an' now, you couldn' see de king's palace ef 'twas

straight afore ye. Bud dis chile knows all 'bout it.”

While speaking, the negro had been carefully removing

some brush and broken branches, which, had it been

light enough to see them, would have appeared to have

naturally drifted in between the old oak and a high

cliff of mingled rock and gravel just behind it. Under

these appeared a large round stone, lying as it might

have lain ever since it first became loosened from the

face of the cliff in some frosty spring, and rolled to its

present position.

But Picter, after casting a searching look into the

darkness surrounding him, applied his strength to this

rock, and soon displacing it, showed that it acted as cover

to the mouth of a tunnel perhaps two feet in diameter,

penetrating the face of the cliff at an acute angle.

“Why, how came that hole there, and where does it

go to?” asked Dora, in astonishment.

“He come dere trew much tribberlation an' hard

work, an' he go to de lan' o' promise. A kin' ob a short

cut ter freedom, dis yer is,” returned Pic, cheerfully.

“Now, den, gib us you lilly paw, missy.”

Dora, without hesitation, put her hand in that of Picter,

who, after lifting her over the brush and the rock,

set her down at the entrance to the tunnel.

“Dere, missy, git down on you han's an' kneeses, an'

creep right frew. I's comin' right arter, soon's I fix up

de brush an' stuff fer ter hide de op'nin'. Has ter be

mighty keerful 'bout dat.”

With fearless obedience, Dora did as directed, and

crept forward some feet into the tunnel, where she paused

until the negro had arranged the disguises of his curious

refuge to his mind.

“Dere, honey,” said he, at length, “now we's all

right, I reckon. You jis' go ahead till you gits to de

end ob dis yer hole. 'Tain't so mighty long, arter all,

an' de lan' ob promise is waitin' fer us at t'oder end.”

The child made no reply. Indeed, the close air and

heavy darkness of the place rendered the mere act of

breathing a difficult one, and she had neither strength nor

courage for speech.

Keeping on as she was told, it was not many minutes,

however, before a waft of fresher air touched her panting

refreshed her aching eyes. Still creeping forward, she

came at last to the end of the tunnel, and rising cautiously

to her feet, stood beneath the sombre sky in what appeared

to be a small, deep valley surrounded on every

side by overhanging cliffs.

“Here we be, missy!” exclaimed Picter, exultantly,

as he stood beside her. “Now gib me you han' again,

an' I'll fotch you to de cabin.”

Putting her hand in his, Dora was silently led across a

little space of grass, to where, beneath the impending

brow of one of the crags, a rude hut had been constructed

of boughs and small trunks of trees. The door was

closed, but yielded to Pic's hand.

“Dere's nobbuddy here. Reckon Scip's gone right

'long,” muttered her, leading in his little companion, and

carefully closing the door behind them.

“Now you set right down on dis yer log, missy, an'

we'm hab a fire an' suffin' to eat 'fore you kin say Jack

Robberson,” continued he, cheerily; and Dora, tired,

faint, and somewhat frightened at her strange situation,

obeyed without a word.

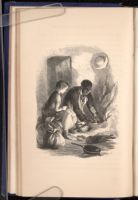

Groping his way to the fireplace at the back of the

hut, the negro drew together some half-burned brands,

added to them from a pile of brush at the side of the fireplace,

lighted them with a match from his pocket, and

soon had a cheery fire crackling up the chimney.

“De smoke goes off in de cracks ob de rocks some

way. You can't neber see it f'um below,” explained he,

turning round to look at Dora, who sat huddled up in

the spot where she had first sunk.

“Pore lilly missy. You's all beat out, an' yore cheeks

is as white as you' han's. Come right up to de fire an'

warm ye, honey. You's awful tired now, isn' you?”

“A little tired, Uncle Pic. But I shall soon be rested

now. What a funny sort of place this is!”

“I'll bet you 'tis, missy. To-morrer we'll look roun'

an' see it. Now, here's some beef an' some bread I lef'

here w'en I comed along. Dem's Yankee vittles, missy.

Tell you, dis chile neber tasted nuffin' sweeter dan de

first mou'ful of Yankee beef, dat he eat in de Union camp.”

“And I shall like it, too, Picter,” said Dora, earnestly;

“for I'm going to be a Yankee all the rest of my life,

after once we get among them.”

“Dat right, honey; you an' Pic cl'ar Yankee f'um dis

minit. Now, chile, here's you bed in dis corner, an'

here's de bery branket dat mist's gib to Cap'n Karl dat

mornin' all handy fer ter wrop ye up.

“Now, missy, you 'member dat it tells in de Bible

'bout how you mus' heave you corn-dodgers inter de

water, an' arter a while dey'll turn up loaves ob w'ite

bread if so be as you has bin good to dem dat stood in

need o' kin'ness.”

“I guess you mean, `Cast thy bread upon the waters,

you?” asked Dora, doubtfully.

“Mabbe de words is fix some sich way; but I's got de

meanin' fus' rate, 'cause mist's tole me all 'bout it; an'

now see, honey, how it's come true 'bout dis yer branket.

Mist's had lots on 'em, an' 'twan't no more dan a corn-dodger

fer her ter gib; bud now it's come back to her

darter w'en she hain't got no oder mortial rag fer ter

wrop herse'f in, an' now it's ekill to a thumpin' big loaf

o' w'ite bread.”

Dora laughed at this queer Scripture reading, and

wrapping herself in the blanket, lay down upon her leafy

bed, where soon she slept as soundly and as sweetly as

if she had still been beneath her father's roof.

As for Picter, he curled himself up almost in the fireplace,

and soon snored portentously.

| CHAPTER VIII. Dora Darling | ||