Arthur Bonnicastle an American novel |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. | CHAPTER XVIII.

HENRY BECOMES A GUEST AT THE MANSION BY FORCE OF

CIRCUMSTANCES. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| CHAPTER XVIII.

HENRY BECOMES A GUEST AT THE MANSION BY FORCE OF

CIRCUMSTANCES. Arthur Bonnicastle | ||

18. CHAPTER XVIII.

HENRY BECOMES A GUEST AT THE MANSION BY FORCE OF

CIRCUMSTANCES.

It was natural that the first business which presented itself

to be done after the departure of Mrs. Sanderson, should be

the reinstatement of my social relations with the Bradfords, yet

how it could be effected without an invitation from them I

could not imagine. I knew that they were all at home, and

that Henry and Claire had called upon them. Day after day

passed, however, and I heard nothing from them. The time

began to drag heavily on my idle hands, when, one pleasant

evening, Mr. Bradford made his appearance at The Mansion.

I had determined upon the course to be pursued whenever I

should meet him, and after some common-place conversation,

I said to him, with all my old frankness, that I wished to open

my heart to him.

“I cannot hide from myself the fact,” I said, “that I am in

disgrace with you and your family. Please tell me what I can

do to atone for a past for which I can make no apology. Do

you wish to see me at your house again? Am I to be shut

out from your family, and shut up here in a palace which your

proscription will make a prison? If I cannot have the respect

of those whom I love best, I may as well die.”

The tears filled my eyes, and he could have had no doubt as

to the genuineness of my emotion, though he made no immediate

reply. He looked at me gravely, and hesitated as if he

were puzzled as to the best way to treat me.

At length he said: “Well, Arthur, I am glad you have got

as far as this—that you have discovered that money cannot buy

everything, and that there are things in the world so much more

without them. It is well, at least, to have learned so much,

but the question with me is: how far will this conviction be permitted

to take practical hold of your life? What are your plans?

What do you propose to do to redeem yourself?”

“I will do anything,” I answered warmly and impulsively.

“That is very indefinite,” he responded, “and if you have

no plans there is no use in our talking further upon the subject.”

“What would you have me do?” I inquired, with a feeling

that he was wronging me.

“Nothing—certainly nothing that is not born of a principle.

If there is no higher purpose in you than that of regaining the

good opinion of your friends and neighbors, you will do nothing.

When you wish to become a man for manhood's sake, your

purpose of life and work will come, and it will be a worthy one.

When your life proceeds from a right principle, you will secure

the respect of everybody, though you will care very little about

it—certainly much less than you care now. My approval will

avail little; you have always had my love and my faith in your

ability to redeem yourself. As for my home it is always open

to you, and there is no event that would make it brighter for

me than to see you making a man's use of your splendid

opportunities.”

We had further talk, but it was not of a character to reassure

me, for I was conscious that I lacked the one thing which he

deemed essential to my improvement. Wealth, with its immunities

and delights, had debauched me, and though I craved the

good opinion of the Bradfords, it was largely because I had

associated Millie with my future. It was my selfishness and

my natural love of approbation that lay at the bottom of it all;

and as soon as I comprehended myself I saw that Mr. Bradford

understood me. He had studied me through and through,

and had ceased to entertain any hope of improvement except

through a change of circumstances.

As I went to the door with him, and looked out into the

They were standing entirely still when the door was opened,

for the light from the hall revealed them. They immediately

moved on, but the sight of them arrested Mr. Bradford on the

step. When they had passed beyond hearing, he turned to me

and, in a low voice, said: “Look to all your fastenings to-night.

There is a gang of suspicious fellows about town, and

already two or three burglaries have been committed. There

may be no danger, but it is well to be on your guard.”

Though I was naturally nervous and easily excited in my imagination,

I was by no means deficient in physical courage,

and no child in physical prowess. I was not afraid of anything

I could see; but the thought of a night-visitation from ruffians

was quite enough to keep me awake, particularly as I could

not but be aware that The Mansion held much that was valuable

and portable, and that I was practically alone. Mr. Bradford's

caution was quite enough to put all my senses on tension

and destroy my power to sleep. That there were men about

the house in the night I had evidence enough, both while I lay

listening, and, on the next morning, when I went into the garden,

where they had walked across the flower-beds.

I called at the Bradfords' the next day, meeting no one, however,

save Mr. Bradford, and reported what I had heard and

seen. He looked grave, and while we were speaking a neighbor

entered who reported two burglaries which had occurred on

the previous night, one of them at a house beyond The Mansion.

“I shall spend the night in the streets,” said Mr. Bradford

decidedly.

“Who will guard your own house?” I inquired.

“I shall depend upon Aunt Flick's ears and Dennis's hands,”

he replied.

Our little city had greatly changed in ten years. The first

railroad had been built, manufactures had sprung up, business

and population had increased, and the whole social aspect of

the place had been revolutionized. It had entirely outgrown

when there was a call for efficient surveillance, the authorities

were sadly inadequate to the occasion. Under Mr. Bradford's

lead, a volunteer corps of constables was organized and

sworn into office, and a patrol established which promised protection

to the persons and property of the citizens.

The following night was undisturbed. No suspicious men

were encountered in the street; and the second night passed

away in the same peaceable manner. Several of the volunteer

constables, supposing that the danger was past, declined to

watch longer, though Mr. Bradford and a faithful and spirited

few still held on. The burglars were believed by him to be

still in the city, under cover, and waiting either for an opportunity

to get away, or to add to their depredations. I do not think

that Mr. Bradford expected his own house to be attacked, but,

from the location of The Mansion, and Mrs. Sanderson's reputation

for wealth, I know that he thought it more than likely

that I should have a visit from the marauders. During these

two nights of watching, I slept hardly more than on the night

when I discovered the loiterers before the house. It began to be

painful, for I had no solid sleep until after the day had dawned.

The suspense wore upon me, and I dreaded the night as much

as if I had been condemned to pass it alone in a forest. I had

said nothing to Jenks or the cook about the matter, and was

all alone in my consciousness of danger, as I was alone in

the power to meet it. Under these circumstances, I called

upon Henry, and asked as a personal favor that he would come

and pass at least one night with me. He seemed but little inclined

to favor my request, and probably would not have done

so had not a refusal seemed like cowardice. At nine o'clock,

however, he made his appearance, and we went immediately to

bed.

Fortified by a sense of protection and companionship, I

sank at once into a slumber so profound that a dozen men

might have ransacked the house without waking me. Though

Henry went to sleep, as he afterwards told me, at his usual

the circumstances into which I had brought him. We both

slept until about one o'clock in the morning, when there came

to me in the middle of a dream a crash which was incorporated

into my dream as the discharge of a cannon and the rattle of

musketry, followed by the groans of the dying. I awoke bewildered,

and impulsively threw my hand over to learn whether

Henry was at my side. I found the clothes swept from the

bed as if they had been thrown off in a sudden waking and

flight, and his place empty. I sprang to my feet, conscious at

the same time that a struggle was in progress near me, but in

the dark. I struck a light, and, all unclad as I was, ran into

the hall. As I passed the door, I heard a heavy fall, and

caught a confused glimpse of two figures embracing and rolling

heavily down the broad stairway. In my haste I almost tumbled

over a man lying upon the floor.

“Hold on to him—here's Arthur,” the man shouted, and I

recognized the voice of old Jenks.

“What are you here for, Jenks?” I shouted.

“I'm hurt,” said Jenks, “but don't mind me. Hold on to

him! hold on to him!”

Passing Jenks, I rushed down the staircase, and found

Henry kneeling upon the prostrate figure of a ruffian, and

holding his hands with a grip of iron. My light had already

been seen in the street; and I heard shouts without, and a

hurried tramping of men. I set my candle down, and was at

Henry's side in an instant, asking him what to do.

“Open the door, and call for help,” he answered between

his teeth. “I am faint and cannot hold on much longer.”

I sprang to the door, and while I was pushing back the bolt

was startled by a rap upon the outside, and a call which I

recognized at once as that of Mr. Bradford. Throwing the

door open, he, with two others, leaped in, and comprehended

the situation of affairs. Closing it behind him, Mr. Bradford

told Henry to let the fellow rise. Henry did not stir. The

ruffian lay helplessly rolling up his eyes, while Henry's head

badly hurt, and had fainted. Mr. Bradford stooped and lifted

his helpless form, as if he had been a child, and bore him up

stairs, while his companions pinioned his antagonist, and

dragged him out of the door, where his associate stood under

guard. The latter had been arrested while running away, on

the approach of Mr. Bradford and his posse.

Depositing his burden upon a bed, Mr. Bradford found

another candle and came down to light it. Giving hurried

directions to his men as to the disposition of the arrested

burglars, he told one of them to bring Aunt Flick at once from

his house, and another to summon a surgeon. In five minutes

the house would have been silent save for the groanings of

poor old Jenks, who still lay where he fell, and the screams of

the cook, who had, at last, been wakened by the din and commotion.

As soon as Henry began to show signs of recovery from his

fainting fit we turned our attention to Jenks, who lay patiently

upon the floor, disabled partly by his fall, and partly by his

rheumatism. Lifting him carefully, we carried him to his bed,

and he was left in my care while Mr. Bradford went back to

Henry.

Old Jenks, who had had a genuine encounter with ruffians

in the dark, seemed to be compensated for all his hurts and

dangers by having a marvelous story to tell and this he told

to me in detail. He had been wakened in the night by a noise.

It seemed to him that somebody was trying to get into the house.

He lay until he felt his bed jarred by some one walking in the

room below. Then he heard a little cup rattle on his table—

a little cup with a teaspoon in it. Satisfied that there was

some one in the house who did not belong in it, he rose, and

undertook to make his way to my room for the purpose of giving

me the information. He was obliged to reach me through

a passage that led from the back part of the house. This he

undertook to do in the stealthy and silent fashion of which he

was an accomplished master, and had reached the staircase

who, taking him at once for an antagonist, knocked him down.

The noise of this encounter woke Henry, who sprang from his

bed, and, in a fierce grapple with the rascal, threw him and

rolled with him to the bottom of the staircase.

I could not learn that the old man had any bones broken, or

that he had suffered much except by the shock upon his nervous

system and the cruel jar he had received in his rheumatic joints.

After a while, having administered a cordial, I left him with the

assurance that I should be up for the remainder of the night

and that he could sleep in perfect safety. Returning to my

room I found Aunt Flick already arrived, and busy with service

at Henry's side. The surgeon came soon afterwards, and

having made a careful examination, declared that Henry had

suffered a bad fracture of the thigh, and that he must on no account

be moved from the house.

At this announcement, Mr. Bradford, Henry and I looked at

one another with a pained and puzzled expression. We said

nothing, but the same thought was running through our minds.

Mrs. Sanderson must know of it, and how would she receive

and treat it? She had a strong prejudice against Henry, of

which we were all aware. Would she blame me for the invitation

that had brought him there? would she treat him well, and

make him comfortable while there?

“I know what you are thinking of,” said Aunt Flick sharply,

“and if the old lady makes a fuss about it I shall give her a

piece of my mind.”

“Let it be small,” said Henry, smiling through his pain.

The adjustment of the fracture was a painful and tedious

process, which the dear fellow bore with the fortitude that was

his characteristic. It was hard for me to think that he had

passed through his great danger and was suffering this pain for

me, though to tell the truth, I half envied him the good fortune

that had demonstrated his prowess and had made him for the

time the hero of the town. These unworthy thoughts I thrust

from my mind, and determined on thorough devotion to the

been the means of saving my life.

It seemed, in the occupation and absorption of the occasion,

but an hour after my waking, before the day began to dawn;

and leaving Aunt Flick with Henry, Mr. Bradford and I retired

for consultation.

It was decided at once that Mrs. Sanderson would be offended

should we withhold from her, for any reason, the news

of what had happened in her house. The question was whether

she should be informed of it by letter, or whether Mr. Bradford

or I should go to her on the morning boat, and tell her the

whole story, insisting that she should remain where she was until

Henry could be moved. Mr. Bradford had reasons of his

own for believing that it was best that she should get her intelligence

from me, and it was decided that while he remained in

or near the house, I should be the messenger to my aunt, and

ascertain her plans and wishes.

Accordingly, bidding Henry a hasty good-morning, and declining

a breakfast for which I had no appetite, I walked down

to the steamer, and paced her decks during all her brief passage,

in the endeavor to dissipate the excitement of which I

had not been conscious until after my departure from the house.

I found my aunt and Mrs. Belden enjoying the morning breeze

on the shady piazza of their hotel. Mrs. Sanderson rose with

excitement as I approached her, while her companion became

as pale as death. Both saw something in my face that betokened

trouble, and neither seemed able to do more than to utter

an exclamation of surprise. Several guests of the house being

near us, I offered my arm to Mrs. Sanderson, and said:

“Let us go to your parlor: I have something to tell you.”

We went up-stairs, Mrs. Belden following us. When we

reached the door, the latter said: “Shall I come in too?”

“Certainly,” I responded. “You will learn all I have to

tell, and you may as well learn it from me.”

We sat down and looked at one another. Then I said:

“We have had a burglary.”

Both ladies uttered an exclamation of terror.

“What was carried away?” said Mrs. Sanderson sharply.

“The burglars themselves,” I answered.

“And nothing lost?”

“Nothing.”

“And no one hurt?”

“I cannot say that,” I answered. “That is the saddest part

of it. Old Jenks was knocked down, and the man who saved

the house came out of his struggle with a badly broken limb.”

“Who was he? How came he in the house?”

“Henry Hulm; I invited him. I was worn out with three

nights of watching.”

Mrs. Sanderson sat like one struck dumb, while Mrs. Belden,

growing paler, fell in a swoon upon the floor. I lifted her

to a sofa, and calling a servant to care for her, after she began

to show signs of returning consciousness, took my aunt into

her bed-room, closed the door, and told her the whole story in

detail. I cannot say that I was surprised by the result. She

always had the readiest way of submitting to the inevitable of

any person I ever saw. She knew at once that it was best for

her to go home, to take charge of her own house, to superintend

the recovery of Henry, and to treat him so well that no

burden of obligation should rest upon her. She knew at once

that any coldness or lack of attention on her part would be

condemned by all her neighbors. She knew that she must put

out of sight all her prejudice against the young man, and so

load him with attentions and benefactions that he could never

again look upon her with indifference, or treat her with even

constructive discourtesy.

While we sat talking, Mrs. Belden rapped at the door, and

entered.

“I am sure we had better go home,” she said, tremblingly.

“That is already determined,” responded my aunt.

With my assistance, the trunks were packed long before the

boat returned, the bills at the hotel were settled, and the ladies

were ready for the little journey.

I had never seen Mrs. Belden so thoroughly deposed from

her self-possession as she seemed all the way home. Her agitation,

which had the air of impatience, increased as we came

in sight of Bradford, and when we arrived at the door of The

Mansion, and alighted, she could hardly stand, but staggered

up the walk like one thoroughly ill. I was equally distressed

and perplexed by the impression which the news had made

upon her, for she had always been a marvel of equanimity and

self-control.

We met the surgeon and Mr. Bradford at the door. They

had good news to tell of Henry, who had passed a quiet day;

but poor old Jenks had shown signs of feverish reaction, and

had been anxiously inquiring when I should return. Aunt

Flick was busy in Henry's room. My aunt mounted at once

to the young man's chamber with the surgeon and myself.

Aunt Flick paused in her work as we entered, made a distant

bow to Mrs. Sanderson, and waited to see what turn affairs

would take, while she held in reserve that “piece of her mind”

which contingently she had determined to hurl at the little mistress

of the establishment.

It was with a feeling of triumph over both Henry and his

spirited guardian, that I witnessed Mrs. Sanderson's meeting

with my friend. She sat down by his bedside, and took his

pale hand in both her own little hands, saying almost tenderly:

“I have heard all the story, so that there is nothing to say,

except for me to thank you for protecting my house, and to

assure you that while you remain here you will be a thousand

times welcome, and have every service and attention you need.

Give yourself no anxiety about anything, but get well as soon

as you can. There are three of us who have nothing in the

world to do but to attend you and help you.”

A tear stole down Henry's cheek as she said this, and she

reached over with her dainty handkerchief, and wiped it away

as tenderly as if he had been a child.

I looked at Aunt Flick, and found her face curiously puckered

in the attempt to keep back the tears. Then my aunt

she could go home and rest, as the family would be quite sufficient

for the nursing of the invalid. The woman could not

say a word. She was prepared for any emergency but this,

and so, bidding Henry good-night, she retired from the room

and the house.

When supper was announced, Mrs. Sanderson and I went

down stairs. We met Mrs. Belden at the foot, who declared

that she was not in a condition to eat anything, and would go

up and sit with Henry. We tried to dissuade her, but she was

decided, and my aunt and I passed on into the dining-room.

Remembering when I arrived there that I had not seen Jenks,

I excused myself for a moment, and as silently as possible

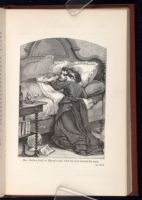

remounted the stairs. As I passed Henry's door, I impulsively

pushed it open. It made no noise, and there, before me,

Mrs. Belden knelt at Henry's bed, with her arms around his

neck and her cheek lying against his own. I pulled back the

door as noiselessly as I had opened it, and half stunned by

what I had seen, passed on through the passage that led to the

room of the old servant. The poor man looked haggard and

wretched, while his eyes shone strangely above cheeks that

burned with the flush of fever. I had been so astonished by

what I had seen that I could hardly give rational replies to his

inquiries.

“I doubt if I weather it, Mr. Arthur; what do you think?”

said he, fairly looking me through to get at my opinion.

“I hope you will be all right in a few days,” I responded.

“Don't give yourself any care. I'll see that you are attended

to.”

“Thank you. Give us your hand.”

I pressed his hand, attended to some trifling service that he

required of me, and went down stairs with a sickening misgiving

concerning my old friend. He was shattered and worn,

and, though I was but little conversant with disease, there was

something in his appearance that alarmed me, and made me

feel that he had reached his death-bed.

With the memory of the scene which I had witnessed in

Henry's room fresh in my mind, with all its strange suggestions,

and with the wild, inquiring look of Jenks still before me,

I had little disposition to make conversation. Yet I looked

up occasionally at my aunt's face, to give her the privilege

of speaking, if she were disposed to talk. She, however, was

quite as much absorbed as myself. She did not look sad.

There played around her mouth a quiet smile, while her eyes

shone with determination and enterprise. Was it possible that

she was thinking that she had Henry just where she wanted

him? Was she glad that she had in her house and hands another

spirit to mould and conquer? Was she delighted that

something had come for her to do, and thus to add variety to

a life which had become tame with routine? I do not know,

but it seemed as if this were the case.

At the close of the meal, I told her of the impression I had

received from Jenks's appearance, and begged her to go to his

room with me, but she declined. There was one presence into

which this brave woman did not wish to pass—the presence

of death. Like many another strongly vitalized nature hers

revolted at dissolution. She could rise to the opposition of

anything that she could meet and master, but the dread

power which she knew would in a few short years, at most,

unlock the clasp by which she held to life and her possessions

filled her with horror. She would do anything for her old

servant at a distance, but she could not, and would not, witness

the process through which she knew her own frame and

spirit must pass in the transition to her final rest.

That night I spent mainly with Jenks, while Mrs. Belden

attended Henry. This was according to her own wish; and

Mrs. Sanderson was sent to bed at her usual hour. Whenever

I was wanted for anything in Henry's room, Mrs. Belden

called me; and, as Jenks needed frequent attention, I got very

little sleep during the night.

Mrs. Sanderson was alarmed by my haggard looks in the

morning, and immediately sent for a professional nurse to attend

stopped.

Tired with staying in-doors, and wishing for a while to separate

myself from the scenes that had so absorbed me, and the

events that had broken so violently in upon my life, I took a

long stroll in the fields and woods. Sitting down at length in the

shade, with birds singing above my head and insects humming

around me, I passed these events rapidly in review, and there

came to me the conviction that Providence had begun to deal

with me in earnest. Since the day of my entrance upon my new

life at The Mansion, I had met with no trials that I had not

consciously brought upon myself. Hardship I had not known.

Sickness and death I had not seen. In the deep sorrows of the

world, in its struggles and pains and self-denials, I had had no part.

Now, change had come, and further change seemed imminent.

How should I meet it? What would be its effect upon me?

For the present my selfish plans and pleasures must be laid

aside, and my life be devoted to others. The strong hand of

necessity was upon me, and there sprang up within me, responsive

to its touch, a manly determination to do my whole duty.

Then the strange scene I had witnessed in Henry's room came

back to me. What relations could exist between this pair, so

widely separated by age, that warranted the intimacy I had

witnessed? Was this woman who had seemed to me so nearly

perfect a base woman? Had she woven her toils about Henry?

Was he a hypocrite? Every event of a suspicious nature

which had occurred was passed rapidly in review. I remembered

his presence at the wharf when she first debarked in the

city, his strange appearance when he met her at the Bradfords

for the first time, the letter I had carried to him written

by her hand, the terrible effect upon her of the news of his

struggle and injury, and many other incidents which I have not

recorded. There was some sympathy between them which I

did not understand, and which filled me with a strange misgiving,

both on account of my sister and myself; yet I knew that

she and Claire were the closest friends, and I had never received

she had returned, she had clung to his room and his side as if

he were her special charge, by duty and by right. One thing

I was sure of: she would never have treated me in the way

she had treated him.

Then there came to me, with a multitude of thoughts and

events connected with my past history, Mrs. Sanderson's singular

actions regarding the picture that had formed with me

the subject of so many speculations and surmises. Who was

the boy? What connection had he with her life and history?

Was she tired of me? Was she repentant for some great injustice

rendered to one she had loved? Was she sorrowing

over some buried hope? Did I stand in the way of the realization

of some desire which, in her rapidly declining years,

had sprung to life within her?

I do not know why it was, but there came to me the consciousness

that events were before me—ready to disclose

themselves—shut from me by a thin veil—which would change

the current of my life; and the purpose I had already formed

of seeking an interview with Mr. Bradford and asking him the

questions I had long desired to ask, was confirmed. I would

do it at once. I would learn my aunt's history, and know the

ground on which I stood. I would pierce the mysteries that

had puzzled me and were still gathering around me, and front

whatever menace they might bear.

| CHAPTER XVIII.

HENRY BECOMES A GUEST AT THE MANSION BY FORCE OF

CIRCUMSTANCES. Arthur Bonnicastle | ||