| Good company for every day in the year | ||

TWO OF THE OLD MASTERS.

By MRS. JAMESON.

WITHIN a short period of about thirty years, that

is, between 1490 and 1520, the greatest painters

whom the world has yet seen were living and working

together. On looking back, we cannot but feel that the

excellence they attained was the result of the efforts and

aspirations of a preceding age; and yet these men were so

great in their vocation, and so individual in their greatness,

that, losing sight of the linked chain of progress, they

seemed at first to have had no precursors, as they have

since had no peers. Though living at the same time, and

most of them in personal relation with each other, the direction

of each mind was different — was peculiar; though

exercising in some sort a reciprocal influence, this influence

never interfered with the most decided originality. These

wonderful artists, who would have been remarkable men in

their time, though they had never touched a pencil, were

Lionardo da Vinci, Michael Angelo, Raphael, Correggio,

Giorgione, Titian, in Italy; and in Germany, Albert Durer.

Of these men, we might say, as of Homer and Shakespeare,

that they belong to no particular age or country, but to all

time, and to the universe. That they flourished together

within one brief and brilliant period, and that each carried

out to the highest degree of perfection his own peculiar

aims, was no casualty; nor are we to seek for the causes of

this surpassing excellence merely in the history of the art as

history of human culture. The fermenting activity of the

fifteenth century found its results in the extraordinary development

of human intelligence in the commencement of the

sixteenth century. We often hear in these days of “the

spirit of the age”; but in that wonderful age three mighty

spirits were stirring society to its depths: — the spirit of

bold investigation into truths of all kinds, which led to the

Reformation; the spirit of daring adventure, which led men

in search of new worlds beyond the eastern and the western

oceans; and the spirit of art, through which men soared even

to the “seventh heaven of invention.”

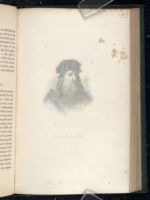

LIONARDO DA VINCI.

Lionardo da Vinci seems to present in his own person a

résumé of all the characteristics of the age in which he lived.

He was the miracle of that age of miracles. Ardent and

versatile as youth; patient and persevering as age; a most

profound and original thinker; the greatest mathematician

and most ingenious mechanic of his time; architect, chemist,

engineer, musician, poet, painter! — we are not only astounded

by the variety of his natural gifts and acquired knowledge,

but by the practical direction of his amazing powers.

The extracts which have been published from MSS. now

existing in his own handwriting show him to have anticipated,

by the force of his own intellect, some of the greatest

discoveries made since his time. These fragments, says Mr.

Hallam, “are, according to our common estimate of the age

in which he lived, more like revelations of physical truths

vouchsafed to a single mind, than the superstructure of its

reasoning upon any established basis. The discoveries which

made Galileo, Kepler, Castelli, and other names illustrious

— the system of Copernicus — the very theories of recent

geologists, are anticipated by Da Vinci within the compass

or on the most conclusive reasoning, but so as to strike us

with something like the awe of preternatural knowledge.

In an age of so much dogmatism, he first laid down the

grand principle of Bacon, that experiment and observation

must be the guides to just theory in the investigation of

nature. If any doubt could be harbored, not as to the right

of Lionardo da Vinci to stand as the first name of the fifteenth

century, which is beyond all doubt, but as to his

originality in so many discoveries which probably no one

man, especially in such circumstances, has ever made, it

must be by an hypothesis not very untenable, that some parts

of physical science had already attained a height which

mere books do not record.”

It seems at first sight almost incomprehensible that, thus

endowed as a philosopher, mechanic, inventor, discoverer,

the fame of Lionardo should now rest on the works he has

left as a painter. We cannot, within these limits, attempt

to explain why and how it is that as the man of science he

has been naturally and necessarily left behind by the onward

march of intellectual progress, while as the poet-painter he

still survives as a presence and a power. We must proceed

at once to give some account of him in the character in

which he exists to us and for us, — that of the great artist.

Lionardo was born at Vinci, near Florence, in the Lower

Val d' Arno, on the borders of the territory of Pistoia.

His father, Piero da Vinci, was an advocate of Florence, —

not rich, but in independent circumstances, and possessed of

estates in land. The singular talents of his son induced

Piero to give him, from an early age, the advantage of the

best instructors. As a child, he distinguished himself by

his proficiency in arithmetic and mathematics. Music he

studied early, as a science as well as an art. He invented

a species of lyre for himself, and sung his own poetical compositions

to his own music, — both being frequently extemporaneous.

its branches; he modelled in clay or wax, or attempted to

draw every object which struck his fancy. His father sent

him to study under Andrea Verrocchio, famous as a sculptor,

chaser in metal, and painter. Andrea, who was an excellent

and correct designer, but a bad and hard colorist,

was soon after engaged to paint a picture of the Baptism of

our Saviour. He employed Lionardo, then a youth, to execute

one of the angles. This he did with so much softness

and richness of color that it far surpassed the rest of the picture;

and Verrocchio from that time threw away his palette,

and confined himself wholly to his works in sculpture and

design; “enraged,” says Vasari, “that a child should thus

excel him.”

The youth of Lionardo thus passed away in the pursuit of

science and of art. Sometimes he was deeply engaged in

astronomical calculations and investigations; sometimes ardent

in the study of natural history, botany, and anatomy;

sometimes intent on new effects of color, light, shadow, or

expression, in representing objects animate or inanimate.

Versatile, yet persevering, he varied his pursuits, but he

never abandoned any. He was quite a young man when he

conceived and demonstrated the practicability of two magnificent

projects. One was, to lift the whole of the Church of

San Lorenzo, by means of immense levers, some feet higher

than it now stands, and thus supply the deficient elevation;

the other project was, to form the Arno into a navigable

canal, as far as Pisa, which would have added greatly to the

commercial advantages of Florence.

It happened about this time that a peasant on the estate

of Piero da Vinci brought him a circular piece of wood, cut

horizontally from the trunk of a very large old fig-tree,

which had been lately felled, and begged to have something

painted on it as an ornament for his cottage. The man

being an especial favorite, Piero desired his son Lionardo

of fancy which was one of his characteristics, took the

panel into his own room, and resolved to astonish his father

by a most unlooked-for proof of his art. He determined to

compose something which should have an effect similar to

that of the Medusa on the shield of Perseus, and almost

petrify beholders. Aided by his recent studies in natural

history, he collected together from the neighboring swamps

and the river-mud all kinds of hideous reptiles, as adders,

lizards, toads, serpents; insects, as moths, locusts; and other

crawling and flying, obscene and obnoxious things; and out

of these he compounded a sort of monster, or chimera, which

he represented as about to issue from the shield, with eyes

flashing fire, and of an aspect so fearful and abominable that

it seemed to infect the very air around. When finished, he

led his father into the room in which it was placed, and the

terror and horror of Piero proved the success of his attempt.

This production, afterwards known as the Rotello

del Fico, from the material on which it was painted, was sold

by Piero secretly for one hundred ducats, to a merchant,

who carried it to Milan, and sold it to the duke for three

hundred. To the poor peasant thus cheated of his Rotello,

Piero gave a wooden shield, on which was painted a heart

transfixed by a dart; a device better suited to his taste and

comprehension. In the subsequent troubles of Milan, Lionardo's

picture disappeared, and was probably destroyed, as an

object of horror, by those who did not understand its value

as a work of art.

The anomalous monster represented on the Rotello was

wholly different from the Medusa, afterwards painted by

Lionardo, and now existing in the Florence Gallery. It

represents the severed head of Medusa, seen foreshortened,

lying on a fragment of rock. The features are beautiful

and regular; the hair already metamorphosed into serpents,

And their long tangles in each other lock,

And with unending involutions show

Their mailéd radiance.”

can never forget it. The ghastly head seems to expire,

and the serpents to crawl into glittering life, as we look

upon it.

During this first period of his life, which was wholly

passed in Florence and its neighborhood, Lionardo painted

several other pictures, of a very different character, and designed

some beautiful cartoons of sacred and mythological

subjects, which showed that his sense of the beautiful, the

elevated, and the graceful, was not less a part of his mind,

than that eccentricity and almost perversion of fancy which

made him delight in sketching ugly, exaggerated caricatures,

and representing the deformed and the terrible.

Lionardo da Vinci was now about thirty years old, in the

prime of his life and talents. His taste for pleasure and

expense was, however, equal to his genius and indefatigable

industry; and, anxious to secure a certain provision for the

future, as well as a wider field for the exercise of his various

talents, he accepted the invitation of Ludovico Sforza il

Moro, then regent, afterwards Duke of Milan, to reside in

his court, and to execute a colossal equestrian statue of his

ancestor Francesco Sforza. Here begins the second period

of his artistic career, which includes his sojourn at Milan,

that is, from 1483 to 1499.

Vasari says that Lionardo was invited to the court of

Milan for the Duke Ludovico's amusement, “as a musician

and performer on the lyre, and as the greatest singer and

improvisatore of his time”; but this is improbable. Lionardo,

in his long letter to that prince, in which he recites

his own qualifications for employment, dwells chiefly on his

skill in engineering and fortification, and sums up his pretensions

the different modes of sculpture in marble, bronze,

and terra-cotta. In painting, also, I may esteem myself

equal to any one, let him be who he may.” Of his musical

talents he makes no mention whatever, though undoubtedly

these, as well as his other social accomplishments, his handsome

person, his winning address, his wit and eloquence,

recommended him to the notice of the prince, by whom he

was greatly beloved, and in whose service he remained for

about seventeen years. It is not necessary, nor would it be

possible here, to give a particular account of all the works

in which Lionardo was engaged for his patron, nor of the

great political events in which he was involved, more by his

position than by his inclination; for instance, the invasion

of Italy by Charles VIII. of France, and the subsequent invasion

of Milan by Louis XII., which ended in the destruction

of the Duke Ludovico. We shall only mention a few

of the pictures he executed. One of these, the portrait of

Lucrezia Crivelli, is now in the Louvre (No. 1091). Another

was the Nativity of our Saviour, in the imperial

collection at Vienna; but the greatest work of all, and by

far the grandest picture which, up to that time, had been

executed in Italy, was the Last Supper, painted on the wall

of the refectory, or dining-room, of the Dominican convent

of the Madonna delle Grazie. It occupied the painter about

two years. Of this magnificent creation of art only the

mouldering remains are now visible. It has been so often

repaired, that almost every vestige of the original painting

is annihilated; but, from the multiplicity of descriptions,

engravings, and copies that exist, no picture is more universally

known and celebrated.

The moment selected by the painter is described in the

twenty-sixth chapter of St. Matthew, twenty-first and

twenty-second verses: “And as they did eat, he said,

Verily, I say unto you, that one of you shall betray me:

of them to say unto him, Lord, is it I?” The knowledge

of character displayed in the heads of the different apostles

is even more wonderful than the skilful arrangement of the

figures and the amazing beauty of the workmanship. The

space occupied by the picture is a wall twenty-eight feet in

length, and the figures are larger than life. The best judgment

we can now form of its merits is from the fine copy

executed by one of Lionardo's best pupils, Marco Uggione,

for the Certosa at Pavia, and now in London, in the collection

of the Royal Academy. Eleven other copies, by

various pupils of Lionardo, painted either during his lifetime

or within a few years after his death, while the picture

was in perfect preservation, exist in different churches and

collections.

Of the grand equestrian statue of Francesco Sforza, Lionardo

never finished more than the model in clay, which

was considered a masterpiece. Some years afterwards, (in

1499,) when Milan was invaded by the French, it was used

as a target by the Gascon bowmen, and completely destroyed.

The profound anatomical studies which Lionardo made for

this work still exist.

In the year 1500, the French being in possession of

Milan, his patron Ludovico in captivity, and the affairs of

the state in utter confusion, Lionardo returned to his native

Florence, where he hoped to re-establish his broken fortunes,

and to find employment. Here begins the third

period of his artistic life, from 1500 to 1513, that is, from

his forty-eighth to his sixtieth year. He found the Medici

family in exile, but was received by Pietro Soderini (who

governed the city as “Gonfaloniere perpetuo”) with great

distinction, and a pension was assigned to him as painter in

the service of the republic.

Then began the rivalry between Lionardo and Michael

Angelo, which lasted during the remainder of Lionardo's

years younger) ought to have prevented all unseemly

jealousy. But Michael Angelo was haughty, and impatient

of all superiority, or even equality; Lionardo, sensitive,

capricious, and naturally disinclined to admit the pretensions

of a rival, to whom he could say, and did say, “I was famous

before you were born!” With all their admiration of each

other's genius, their mutual frailties prevented any real

good-will on either side. The two painters competed for

the honor of painting in fresco one side of the great Council-hall

in the Palazzo Vecchio at Florence. Each prepared

his cartoon; each, emulous of the fame and conscious of the

abilities of his rival, threw all his best powers into his work.

Lionardo chose for his subject the Defeat of the Milanese

general, Niccolò Piccinino, by the Florentine army in 1440.

One of the finest groups represented a combat of cavalry

disputing the possession of a standard. “It was so wonderfully

executed, that the horses themselves seemed animated

by the same fury as their riders; nor is it possible to describe

the variety of attitudes, the splendor of the dresses

and armor of the warriors, nor the incredible skill displayed

in the forms and actions of the horses.”

Michael Angelo chose for his subject the moment before

the same battle, when a party of Florentine soldiers bathing

in the Arno are surprised by the sound of the trumpet calling

them to arms. Of this cartoon we shall have more to

say in treating of his life. The preference was given to

Lionardo da Vinci. But, as Vasari relates, he spent so

much time in trying experiments, and in preparing the wall

to receive oil painting, which he preferred to fresco, that in

the interval some changes in the government intervened,

and the design was abandoned. The two cartoons remained

for several years open to the public, and artists flocked from

every part of Italy to study them. Subsequently they were

cut up into separate parts, dispersed, and lost. It is curious

exists; of Lionardo's, not one. From a fragment which existed

in his time, but which has since disappeared, Rubens

made a fine drawing, which was engraved by Edelinck, and

is known as the Battle of the Standard.

It was a reproach against Lionardo, in his own time, that

he began many things and finished few; that his magnificent

designs and projects, whether it art or mechanics, were seldom

completed. This may be a subject of regret, but it is

unjust to make it a reproach. It was in the nature of the

man. The grasp of his mind was so nearly superhuman,

that he never, in anything he effected, satisfied himself or

realized his own vast conceptions. The most exquisitely

finished of his works, those that in the perfection of the execution

have excited the wonder and despair of succeeding

artists, were put aside by him as unfinished sketches. Most

of the pictures now attributed to him were wholly or in

part painted by his scholars and imitators from his cartoons.

One of the most famous of these was designed for the altar-piece

of the church of the convent called the Nunziata. It

represented the Virgin Mary seated in the lap of her

mother, St. Anna, having in her arms the infant Christ,

while St. John is playing with a lamb at their feet; St.

Anna, looking on with a tender smile, rejoices in her divine

offspring. The figures were drawn with such skill, and the

various expressions proper to each conveyed with such inimitable

truth and grace, that, when exhibited in a chamber of

the convent, the inhabitants of the city flocked to see it, and

for two days the streets were crowded with people, “as if it

had been some solemn festival”; but the picture was never

painted, and the monks of the Nunziata, after waiting long

and in vain for their altar-piece, were obliged to employ

other artists. The cartoon, or a very fine repetition of it,

is now in the possession of the Royal Academy, and it must

not be confounded with the St. Anna in the Louvre, a more

fantastic and apparently an earlier composition.

Lionardo, during his stay at Florence, painted the portrait

of Ginevra Benci, already mentioned, in the memoir of

Ghirlandajo, as the reigning beauty of her time; and also

the portrait of Mona Lisa del Giocondo, sometimes called

La Joconde. On this last picture he worked at intervals

for four years, but was still unsatisfied. It was purchased

by Francis I. for four thousand golden crowns, and is now

in the Louvre. We find Lionardo also engaged by Cæsar

Borgia to visit and report on the fortifications of his territories,

and in this office he was employed for two years. In

1514 he was invited to Rome by Leo X., but more in his

character of philosopher, mechanic, and alchemist, than as a

painter. Here he found Raphael at the height of his fame,

and then engaged in his greatest works, — the frescos of

the Vatican. Two pictures which Lionardo painted while

at Rome — the Madonna of St. Onofrio, and the Holy Family,

painted for Filiberta of Savoy, the Pope's sister-in-law

(which is now at St. Petersburg) — show that even this

veteran in art felt the irresistible influence of the genius of

his young rival. They were both Raffaellesque in the subject

and treatment.

It appears that Lionardo was ill-satisfied with his sojourn

at Rome. He had long been accustomed to hold the first

rank as an artist wherever he resided; whereas at Rome he

found himself only one among many who, if they acknowledged

his greatness, affected to consider his day as past.

He was conscious that many of the improvements in the

arts which were now brought into use, and which enabled

the painters of the day to produce such extraordinary effects,

were invented or introduced by himself. If he could no

longer assert that measureless superiority over all others

which he had done in his younger days, it was because he

himself had opened to them new paths to excellence. The

arrival of his old competitor Michael Angelo, and some

slight on the part of Leo X., who was annoyed by his speculative

to him, all added to his irritation and disgust. He left

Rome, and set out for Pavia, where the French king Francis

I. then held his court. He was received by the young

monarch with every mark of respect, loaded with favors,

and a pension of seven hundred gold crowns settled on him

for life. At the famous conference between Francis I. and

Leo X. at Bologna, Lionardo attended his new patron, and

was of essential service to him on that occasion. In the following

year, 1516, he returned with Francis I. to France,

and was attached to the French court as principal painter.

It appears, however, that during his residence in France he

did not paint a single picture. His health had begun to

decline from the time he left Italy; and, feeling his end

approach, he prepared himself for it by religious meditation,

by acts of charity, and by a most conscientious distribution

by will of all his worldly possessions to his relatives and

friends. At length, after protracted suffering, this great

and most extraordinary man died at Cloux, near Amboise,

on the 2d of May, 1519, being then in his sixty-seventh

year. It is to be regretted that we cannot wholly credit

the beautiful story of his dying in the arms of Francis I.,

who, as it is said, had come to visit him on his death-bed. It

would, indeed, have been, as Fuseli expressed it, “an honor

to the king, by which Destiny would have atoned to that

monarch for his future disaster at Pavia,” had the incident

really happened, as it has been so often related by biographers,

celebrated by poets, represented with a just pride by

painters, and willingly believed by all the world; but the

well-authenticated fact that the court was on that day at St.

Germain-en-Laye, whence the royal ordinances are dated,

renders the story, unhappily, very doubtful.

TITIAN.

Tiziano Vecelli was born at Cadore in the Friuli, a

district to the north of Venice, where the ancient family of

the Vecelli had been long settled. There is something very

amusing and characteristic in the first indication of his love

of art; for while it is recorded of other young artists that

they took a piece of charcoal or a piece of slate to trace the

images in their fancy, we are told that the infant Titian,

with an instinctive feeling prophetic of his future excellence

as a colorist, used the expressed juice of certain flowers to

paint a figure of a Madonna. When he was a boy of nine

years old his father, Gregorio, carried him to Venice and

placed him under the tuition of Sebastian Zuccato, a

painter and worker in mosaic. He left this school for

that of the Bellini, where the friendship and fellowship of

Giorgione seems early to have awakened his mind to new

ideas of art and color. Albert Durer, who was at Venice

in 1494, and again in 1507, also influenced him. At this

time, when Titian and Giorgione were youths of eighteen

and nineteen, they lived and worked together. It has been

related that they were employed in painting the frescos of

the Fondaco dei Tedeschi. The preference being given to

Titian's performance, which represented the story of Judith,

caused such a jealousy between the two friends, that they

ceased to reside together; but at this time, and for some

years afterwards, the influence of Giorgione on the mind

and the style of Titian was such that it became difficult to

distinguish their works; and on the death of Giorgione,

Titian was required to complete his unfinished pictures.

This great loss to Venice and the world left him in the

prime of youth without a rival. We find him for a few

years chiefly employed in decorating the palaces of the

Venetian nobles, both in the city and on the mainland.

by his biographers is the Presentation of the Virgin in

the Temple, a large picture, now in the Academy of

Arts at Venice; and the first portrait recorded is that of

Catherine, Queen of Cyprus, of which numerous repetitions

and copies were scattered over all Italy. There is

a fine original in the Dresden Gallery. This unhappy

Catherine Cornaro, the “daughter of St. Mark,” having

been forced to abdicate her crown in favor of the Venetian

state, was at this time living in a sort of honorable captivity

at Venice. She had been a widow for forty years, and he

has represented her in deep mourning, holding a rosary in

her hand, — the face still bearing traces of that beauty for

which she was celebrated.

It appears that Titian was married about 1512, but of his

wife we do not hear anything more. It is said that her

name was Lucia, and we know that she bore him three children,

— two sons, and a daughter called Lavinia. It seems

probable, on a comparison of dates, that she died about the

year 1530.

One of the earliest works on which Titian was engaged

was the decoration of the convent of St. Antony, at Padua,

in which he executed a series of frescos from the life of St.

Antony. He was next summoned to Ferrara by the Duke

Alphonso I., and was employed in his service for at least

two years. He painted for this prince the beautiful picture

of Bacchus and Ariadne, which is now in the National Gallery,

and which represents on a small scale an epitome of

all the beauties which characterize Titian, in the rich, picturesque,

animated composition, in the ardor of Bacchus, who

flings himself from his car to pursue Ariadne; the dancing

bacchanals, the frantic grace of the bacchante, and the little

joyous satyr in front, trailing the head of the sacrifice. He

painted for the same prince two other festive subjects: one

in which a nymph and two men are dancing, while another

and cupids are sporting round a statue of Venus.

There are here upwards of sixty figures in every variety

of attitude, some fluttering in the air, some climbing the

fruit-trees, some shooting arrows, or embracing each other.

This picture is known as the Sacrifice to the Goddess of

Fertility. While it remained in Italy, it was a study for

the first painters, — for Poussin, the Carracci, Albano, and

Fiamingo the sculptor, so famous for his models of children.

At Ferrara, Titian also painted the portrait of the first wife

of Alphonso, the famous and infamous Lucrezia Borgia;

and here also he formed a friendship with the poet Ariosto,

whose portrait he painted.

At this time he was invited to Rome by Leo X., for

whom Raphael, then in the zenith of his powers, was executing

some of his finest works. It is curious to speculate

what influence these two distinguished men might have

exercised on each other had they met; but it was not so

decreed. Titian was strongly attached to his home and his

friends at Venice; and to his birthplace, the little town of

Cadore, he paid an annual summer visit. His long absence

at Ferrara had wearied him of courts and princes; and,

instead of going to Rome to swell the luxurious state of Leo

X., he returned to Venice and remained there stationary for

the next few years, enriching its palaces and churches with

his magnificent works. These were so numerous that it

would be in vain to attempt to give an account even of those

considered as the finest among them. Two, however, must be

pointed out as pre-eminent in beauty and celebrity. First,

the Assumption of the Virgin, painted for the Church of

Santa Maria de' Frari, and now in the Academy of the

Fine Arts at Venice, and well known from the magnificent

engraving of Schiavone — the Virgin is soaring to heaven

amid groups of angels, while the apostles gaze upwards;

and, secondly, the Death of St. Peter Martyr when attacked

the prostrate victim and the ferocity of the murderer, the

attendant flying “in the agonies of cowardice,” with the trees

waving their distracted boughs amid the violence of the tempest,

have rendered this picture famous as a piece of scenic

poetry as well as of dramatic expression.

The next event of Titian's life was his journey to Bologna

in 1530. In that year the Emperor Charles V. and Pope

Clement VII. met at Bologna, each surrounded by a brilliant

retinue of the most distinguished soldiers, statesmen,

and scholars, of Germany and Italy. Through the influence

of his friend Aretino, Titian was recommended to the Cardinal

Ippolito de' Medici, the Pope's nephew, through whose

patronage he was introduced to the two potentates who sat

to him. One of the portraits of Clement VII., painted at

this time, is now in the Bridgewater Gallery. Charles V.

was so satisfied with his portrait, that he became the zealous

friend and patron of the painter. It is not precisely known

which of several portraits of the Emperor painted by Titian

was the one executed at Bologna on this memorable occasion,

but it is supposed to be that which represents him on

horseback charging with his lance, now in the Royal Gallery

at Madrid, and of which Mr. Rogers possesses the original

study. The two portraits of Ippolito de' Medici in the Pitti

Palace and the Louvre were also painted at this period.

After a sojourn of some months at Bologna, Titian returned

to Venice loaded with honors and rewards. There

was no potentate, prince, or poet, or reigning beauty, who

did not covet the honor of being immortalized by his pencil.

He had, up to this time, managed his worldly affairs with

great economy; but now he purchased for himself a house

opposite to Murano, and lived splendidly, combining with

the most indefatigable industry the liveliest enjoyment of

existence; his favorite companions were the architect Sansovino

and the witty profligate Pietro Aretino. Titian has

nothing can be said in his excuse, except that the proudest

princes in Europe condescended to flatter and caress this

unprincipled literary ruffian, who was pleased to designate

himself as the “friend of Titian, and the scourge of princes.”

One of the finest of Titian's portraits is that of Aretino, in

the Munich Gallery.

Thus in the practice of his art, in the society of his

friends, and in the enjoyment of the pleasures of life, did

Titian pass several years. The only painter of his time

who was deemed worthy of competing with him was Licinio

Regillo, better known as Pordenone. Between Titian and

Pordenone there existed not merely rivalry, but a personal

hatred, so bitter that Pordenone affected to think his life in

danger, and when at Venice painted with his shield and

poniard lying beside him. As long as Pordenone lived,

Titian had a spur to exertion, to emulation. All the other

good painters of the time, Palma, Bonifazio, Tintoretto,

were his pupils or his creatures; Pordenone would never

owe anything to him; and the picture called the St. Justina,

at Vienna, shows that he could equal Titian on his own

ground.

After the death of Pordenone at Ferrara, in 1539, Titian

was left without a rival. Everywhere in Italy art was on

the decline: Lionardo, Raphael, Correggio, had all passed

away. Titian himself, at the age of sixty, was no longer

young, but he still retained all the vigor and the freshness

of youth; neither eye nor hand, nor creative energy of mind

had failed him yet. He was again invited to Ferrara, and

painted there the portrait of the old Pope Paul III. He

then visited Urbino, where he painted for the Duke the famous

Venus which hangs in the Tribune of the Florence Gallery,

and many other pictures. He again, by order of Charles

V., repaired to Bologna, and painted the Emperor, standing,

and by his side a favorite Irish wolf-dog. This picture was

death was sold into Spain, and is now at Madrid.

Pope Paul III. invited him to Rome, whither he repaired

in 1548. There he painted that wonderful picture of the

old Pope with his two nephews, the Duke Ottavio and Cardinal

Farnese, which is now at Vienna. The head of the

Pope is a miracle of character and expression. A keen-visaged,

thin little man, with meagre fingers like birds' claws,

and an eager cunning look, riveting the gazer like the eye of

a snake, — nature itself! — and the Pope had either so little

or so much vanity as to be perfectly satisfied. He rewarded

the painter munificently; he even offered to make his son

Pomponio Bishop of Ceneda, which Titian had the good

sense to refuse. While at Rome he painted several pictures

for the Farnese family, among them the Venus and

Adonis, of which a repetition is in the National Gallery,

and a Danaë which excited the admiration of Michael Angelo.

At this time Titian was seventy-two.

He next, by command of Charles V., repaired to Augsburg,

where the Emperor held his court: eighteen years

had elapsed since he first sat to Titian, and he was now

broken by the cares of government, — far older at fifty than

the painter at seventy-two. It was at Augsburg that the

incident occurred which has been so often related: Titian

dropped his pencil, and Charles, taking it up and presenting

it, replied to the artist's excuses that “Titian was worthy of

being served by Cæsar.” This pretty anecdote is not without

its parallel in modern times. When Sir Thomas Lawrence

was painting at Aix-la-Chapelle, as he stooped to place

a picture on his easel, the Emperor of Russia anticipated him,

and, taking it up, adjusted it himself; but we do not hear

that he made any speech on the occasion. When at Augsburg,

Titian was ennobled and created a count of the empire,

with a pension of two hundred gold ducats, and his son

Pomponio was appointed canon of the cathedral of Milan.

in great favor with his successor Philip II., for whom

he painted several pictures. It is not true, however, that

Titian visited Spain. The assertion that he did so rests on

the sole authority of Palomino, a Spanish writer on art, and,

though wholly unsupported by evidence, has been copied

from one book into another. Later researches have proved

that Titian returned from Augsburg to Venice; and an

uninterrupted series of letters and documents, with dates of

time and place, remain to show that, with the exception of

this visit to Augsburg and another to Vienna, he resided

constantly in Italy, and principally at Venice, from 1530 to

his death. Notwithstanding the compliments and patronage

and nominal rewards he received from the Spanish court,

Titian was worse off under Philip II. than he had been

under Charles V.: his pension was constantly in arrears;

the payments for his pictures evaded by the officials; and

we find the great painter constantly presenting petitions

and complaints in moving terms, which always obtained gracious

but illusive answers. Philip II., who commanded the

riches of the Indies, was for many years a debtor to Titian

for at least two thousand gold crowns; and his accounts

were not settled at the time of his death. For Queen

Mary of England, who wished to patronize one favored by

her husband, Titian painted several pictures, some of which

were in the possession of Charles I.; others had been carried

to Spain after the death of Mary, and are now in the

Royal Gallery at Madrid.

Besides the pictures painted by command for royal and

noble patrons, Titian, who was unceasingly occupied, had

always a great number of pictures in his house which he

presented to his friends, or to the officers and attendants of

the court, as a means of procuring their favor. There is

extant a letter of Aretino, in which he describes the scene

which took place when the Emperor summoned his favorite

says, “the most flattering testimony to his excellence to

behold, as soon as it was known that the divine painter was

sent for, the crowds of people running to obtain, if possible,

the productions of his art; and how they endeavored to

purchase the pictures, great and small, and everything that

was in the house, at any price; for everybody seems assured

that his august majesty will so treat his Apelles that he

will no longer condescend to exercise his pencil except to

oblige him.”

Years passed on, and seemed to have no power to quench

the ardor of this wonderful old man. He was eighty-one

when he painted the Martyrdom of St. Laurence, one of

his largest and grandest compositions. The Magdalen, the

half-length figure with uplifted streaming eyes, which he

sent to Philip II., was executed even later; and it was not

till he was approaching his ninetieth year that he showed

in his works symptoms of enfeebled powers; and then it

seemed as if sorrow rather than time had reached him and

conquered him at last. The death of many friends, the

companions of his convivial hours, left him “alone in his

glory.” He found in his beloved art the only refuge from

grief. His son Pomponio was still the same worthless

profligate in age that he had been in youth. His son Orazio

attended upon him with truly filial duty and affection, and

under his father's tuition had become an accomplished artist;

but as they always worked together, and on the same canvas,

his works are not to be distinguished from his father's.

Titian was likewise surrounded by painters who, without

being precisely his scholars, had assembled from every part

of Europe to profit by his instructions. The early morning

and the evening hour found him at his easel; or lingering

in his little garden (where he had feasted with Aretino and

Sansovino, and Bembo and Ariosto, and “the most gracious

Virginia,” and “the most beautiful Violante”), and gazing

and bright career fast hastening to its close; — not that such

anticipations clouded his cheerful spirit, — buoyant to the

last! In 1574, when he was in his ninety-seventh year,

Henry III. of France landed at Venice on his way from

Poland, and was magnificently entertained by the Republic.

On this occasion the King visited Titian at his own house,

attended by a numerous suite of princes and nobles. Titian

entertained them with splendid hospitality; and when the

King asked the price of some pictures which pleased him,

he presented them as a gift to his Majesty, and every one

praised his easy and noble manners and his generous

bearing.

Two years more passed away, and the hand did not yet

tremble nor was the eye dim. When the plague broke

out in Venice, the nature of the distemper was at first mistaken,

and the most common precautions neglected; the

contagion spread, and Titian and his son were among those

who perished. Every one had fled, and before life was

extinct some ruffians entered his chamber and carried off,

before his eyes, his money, jewels, and some of his pictures.

His death took place on the 9th of September, 1575. A

law had been made during the plague that none should be

buried in the churches, but that all the dead bodies should

be carried beyond the precincts of the city; an exception,

however, even in that hour of terror and anguish, was made

in favor of Titian. His remains were borne with honor to

the tomb, and deposited in the Church of Santa Maria de'

Frari, for which he had painted his famous Assumption.

There he lies beneath a plain black marble slab, on which

is simply inscribed,

“TIZIANO VECELLIO.”

In the year 1794 the citizens of Venice resolved to erect

a noble and befitting monument to his memory. Canova

the extinction of the Republic, prevented the execution of

this project. Canova's magnificent model was appropriated

to another purpose, and now forms the cenotaph of the

Archduchess Christina, in the Church of the Augustines

at Vienna.

This was the life and death of the famous Titian. He

was pre-eminently the painter of nature; but to him nature

was clothed in a perpetual garb of beauty, or rather to him

nature and beauty were one. In historical compositions

and sacred subjects he has been rivalled and surpassed,

but as a portrait painter never; and his portraits of celebrated

persons have at once the truth and the dignity of

history.

| Good company for every day in the year | ||