Martin Merrivale his X mark |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. | XXIX.

OTHER CHANGES. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| XXIX.

OTHER CHANGES. Martin Merrivale | ||

29. XXIX.

OTHER CHANGES.

CALEB THORNE was sitting

on the lounge, with

his elbows on his knees and

his face between his hands.

Martin spoke to him, but he

did not look up.

“He has not been in his

right mind for several days,”

said Martha, in a low tone;

“but we did not think him

seriously deranged until Saturday.

He was hoeing corn, when all at once he began to

weep. Jared asked him what the matter was.”

“And he said it was too bad to chop the frogs so!” spoke up

the boy Amos, with an excited countenance. “He thought the

ground was all frogs, and he could n't put his hoe down without

cutting 'em! And last night he took grandfather one side, and

asked him what we kept those three bears chained for, under the

shed.”

“Mr. Thorne!” said Martin, again, taking his hand, “how do

you do this morning?”

“The water keeps saying, `Whether or no! whether or no!'

haggard face.

“Do you know me, Mr. Thorne?”

“You are the officer they sent for; but I am not afraid of you.

Only have me shaved before I am taken into court; and look

here! — let the barber be under oath. — Hark! there it is again!

`Whether or no! whether or no!' What is the crime?

Arson?”

“My dear Caleb,” replied Martin, “there is no crime. I am

not an officer. We are all your friends.”

“An old story! I know that stratagem. But you need n't be

afraid to tell me the worst. Arson and murder, I think it is.

But they can prove nothing. It was an accidental explosion.

They took Alice from me, and, because I went for her, put her

down in the pond. The boys will find her when they go a

fishing.”

“Here I am, father! Dear, dear father! here I am! Don't

you know me?” cried the blind girl, kneeling at his feet, and

embracing them.

“Here is your child, Mr. Thorne,” said Martin, placing his

arm affectionately around her, and laying Caleb's hand upon her

breast. “This is indeed Alice.”

“A cruel sham!” returned Caleb, shaking his head. “I am

sick to-day! If I was well I would explain it all. But I

have eaten too much salt fish, and the water troubles me.”

“I know you are unwell, Mr. Thorne. I would talk no more

just now; but lie down, and try to sleep.”

“You are a model officer! There 's no resisting such politeness.”

And Caleb, throwing his feet upon the lounge, allowed

Martin to arrange the pillows beneath his head. “But to sleep

elbow. — “There is no law to burn a man, is there?”

“None whatever.”

“Not even for murder or arson? Then let them do their

worst! Fire is the only thing I am afraid of. Let some one

keep the flies off and I think I can sleep.” He lay down, and

closed his eyes, but sprang up again almost immediately. “See

here, Mr. Officer! what does it mean? `Whether or no! whether

or no!' I don't understand it. Does it mean that I am to be

hung, whether I am guilty or not?”

“O, no,” returned Martin; “it has sung the same tune for

more than seven years. It is the old song of the water. It don't

allude to you at all.”

“Wake me in season,” said Caleb, lying down again. “If I

should be tardy in court, they would call me a coward.”

Thereupon Amos hastened from the room, exploding with

laughter. Martin drew the weeping Alice gently away, while

Jared took his seat by Caleb, and frightened the flies from his

face with a fan.

“O, let me do that!” said old Mr. Doane, entering the room.

“It will be fun for me.”

“Very well, father,” answered Jared, resigning his seat and

the fan. “Be careful and not wake him.”

The old man appeared delighted with the employment. Now

he flourished the fan with ostentatious zeal; then he would seek

to entrap the flies in his hands by strategy. He was thus engaged

when Caleb, in the course of a few minutes, awoke.

Caleb: “What have they changed judges for?”

Old man: “I like some light employment; and this is just the

thing to suit me.”

Caleb: “You are a better judge than the other one.”

Old man, highly gratified: “I am a good judge of old

cheese. I can tell a good kite, and the difference between a

whippoorwill and a night-hawk.”

Caleb: “I did n't like the black horns the other judge wore.

Now let the witness appear. I can destroy her testimony; but

if you will say nothing about the diamonds, I will not speak of

the ring.”

Old Mr. Doane, with a shrewd glance at Martin: “I 'll have

the whole story from him now; don't say anything! What diamonds,

Mr. Thorne?”

Caleb: “They say I stole them, and swallowed them. If it

is proved, I am to be cut open, for the recovery of the property.

I know there are diamonds in me, for I feel them burn and

prickle; but I never swallowed them. Ask her how long she has

been a policeman. Sally Hicks! can you swear that Alice's

mother did not die a natural death? Hold the sword to her

throat, and let her answer!”

Old man: “It is a mixed up mess. I can't make head or

tail of it.”

Caleb, sternly: “I charge you not to let that witness

escape! It is Sally Hicks in disguise. I know her by the wart.

She swore that she had seen me dead drunk in the streets more than

a dozen times; that 's what sent me to the House of Correction.

Now I will have the perjury proved. We will see then what she

will say about the murder. I am sure my wife died a natural

death; and those who say I killed her shall suffer the penalty of

the law.”

Caleb's insanity appeared to grow upon him until afternoon.

He thought Mr. Murray a hangman; and once caught Alice by

had given him great imaginary trouble, — and declaring that her

crying gave him cramps in the stomach. But at length his

strength began to fail him; he was got to bed, and, sinking into

a quiet slumber, he slept soundly for several hours.

It was night when he awoke. Meantime a storm came on;

clouds, that lay like crouching monsters in the sultry west all the

afternoon, rose up and shook dull thunder from their backs; the

lightning grew frequent and vivid; and, as the evening closed, the

earth became canopied in black. A sudden burst of the storm

seemed to have disturbed Caleb's sleep.

“They loaded the cannon with camphene, or it would never

have burst,” he said, in a faint voice. “The people keep shouting,

`Bob Synders was blown to flinders.' Some say his buttons

killed a flock of pigeons; but I don't believe it.”

Martin, who sat by his bedside, conversing with Miss Doane in

whispers, — Alice, worn out, had fallen asleep with her head on

Martha's lap, — arose and bent over him, asking him if he was

comfortable.

“I think I have been dreaming,” replied Caleb, vacantly.

“What place is this?”

“You are in Mr. Doane's house. Do you know me?”

“I remember you very well, but I can't speak your name. I

think you were very kind to my poor blind girl; and I did you

some wrong. My head is not quite clear. What was that?”

“A flash of lightning,” replied Martin.

“What sharp thunder!” said Caleb. “It must have struck

not far off. Is it the wind that rushes so?”

“The wind — and now the rain lashes the windows. It is a

terrible night.”

“O, yes! I know that voice. You are Mr. Merrivale. I

am very weak, or I would thank you. You were a brother to

Alice — she always called you so. I was a fool to be jealous; I

hated you and feared you. I hope you forgive me.”

“With all my heart, sir!”

“You are very good. I trust I shall live to thank you. I am

not clear yet; and, if you will believe me, this bleeding has

taken away all my strength. I had seven veins opened.”

“Your wounds are healed now,” said Martin, “and you will be

better soon. Take this cordial, and it will strengthen you.”

Caleb was about to drink, but smelling the contents of the

glass, he shook his head, and put it feebly aside.

“It is brandy,” said Martin. “Before you slept, you made us

promise to have some for you when you awoke. The doctor said

if you should be very weak a little would help you.”

“I am sick — deadly sick!” moaned Caleb. “But I cannot

taste it. I have broken a hundred oaths in my lifetime — for I

have been a wretched sinner all my days; — but the oath I made

to Alice before she died — I will not break that. It is my last

hope of salvation.”

“Dear, dear father! here I am! — here I am, your own

Alice!” cried the blind girl, flinging herself upon his bosom.

“Don't you know me? — don't you know your own dear Alice?”

“I think you should be my child,” said Caleb, weeping.

“Heaven is kind! I buried you last week, and my heart with

you. I am afraid this is but a dream for my punishment, my

poor girl!”

“No, no! the other was a dream. I am indeed your Alice —

your dear Alice!”

“This is your hair, and your face, — I cannot be mistaken in

I have had bad dreams! They have left me very weak. If

I had a little brandy to drink!”

Once more Martin offered Caleb the tumbler; but he put it

aside again, after touching it with his lips.

“When I reflect what my life has been, I cannot drink! It

seems only a month or two since I was young like you, Mr. Merrivale;

and I had high hopes.— Ashes — ashes — ashes! —

Take the brandy away.”

The sick man slept at intervals during the night; but his slumbers

were light, and the least noise in the room awoke him. At

half-past two he called, “Mary.”

“It was my mother's name,” said Alice, with a stifled sob.

“She has been with me, but she is gone now,” murmured

Caleb. “She is coming again soon, and I am to go with her.

Bless you, bless you, my child! You forgive your poor father,

do you?”

The blind girl's sobs made answer.

“How the room brightens!” whispered Caleb, after a long

silence. “It is Mary again! there! there!”

Not long after, Martin took the blind girl from his arms. They

were heavy and cold. His lips moved no more. “Mary” had

come for him, and they were gone together.

Only Martin could afford Alice any consolation. When the

first burst of her grief had subsided, he folded her in his arms, and

sat down by the open window of her chamber. The storm

had spent its fury; the clouds chased each other across the

blue; a few stars shone faintly, and in high heaven soared the

glittering moon. And there the young man sat and looked

forth, with the blind girl lying motionless in his arms, until the

a film, and the conquering day unfurled his crimson banners on

the hills. Then gently he arose and carried Alice, sleeping, to

the bed, laid her gently down, kissed her, and stole softly from

the chamber.

Grief for her father's death proved a violent strain upon the

blind orphan's slender life. But she did not want for friends;

Miss Doane watched over her with a mother's care and love; and

at the parsonage, to which she was removed about a week after

the funeral, she was more petted than ever. Martin came out

frequently from Boston to see her, bringing delicate fruits and

other gifts to cheer her; and when he was absent, Junius and his

sister filled his place.

“Come, my darling,” said Margaret, one fair summer morning,

“I have loaded my basket with good things, and now let us see if

we can find anybody that wants them. Do you feel able to go?”

“O, yes,” answered Alice, with a smile of pleasure. “I like

so well to go with you! It makes me glad when you give to

these poor people, and they thank you with such full hearts!”

“Junius will take us in the buggy,” cried Margaret, with

inspiring cheerfulness. “He will leave us somewhere; and

when we have disposed of our load, we can walk home. If the

dew is off the grass, we will come through the fields.”

“That will be nice!” said Alice. “It does me good to walk,

if I don't get too tired.”

“Hurra, you fellows!” exclaimed Junius, gayly, at the door.

“The twenty-three-year-old colt is waiting patiently. Is this

the basket that 's going to ride? Give me that little hand of

yours, Alice. Laura shall put in the basket, and I will put you

in after.”

“If anybody calls, shall I say you will be back soon?” inquired

Laura. This was the fifth question she had asked with reference

to the morning's excursion; but Margaret did not see fit to gratify

her curiosity. “If you go by our house, I wish you would

ask how mother is,” she cried, as the party drove away.

“I don't think we shall pass your house,” replied Margaret,

smiling. “Laura is very anxious to know where we are going,

Alice, — should n't you think so?”

“Why is she?”

“Can't you guess? You heard the doleful tale she told last

night about her family, did n't you?”

“She said her father had been drinking again. He had taken

all her mother's money to buy liquor, and beaten the children.

It is too bad!” said the sympathetic Alice. “I feel so sorry

for poor Laura! She is a real good girl, — don't you think she

is?”

“A very good girl. She has lived with us nearly a year, and

during all this time I have had no serious fault to find with her.”

“Yet Mrs. Merrivale thought her obstinate and lazy,” laughed

Junius. “She warned you against hiring her, you remember.”

“I have found her industrious and faithful,” returned Margaret.

“Perhaps Mrs. Merrivale did not treat her so kindly as you

do,” said Alice. “Laura will do anything for one she loves;

but I don't think she would like to be driven. I was in hopes

you were going to see her folks this morning.”

“So indeed I am, dear child. I told her I should not pass the

house: it is my intention to stop. I am sorry now I did not tell

her the truth, — she looked so disappointed. But we will surprise

her when we return.”

Junius left Margaret, Alice and the basket, at the door of a

low, dilapidated tenement, situated on an unfrequented road a

little back from the village. On entering, they found that

Laura's story had not been exaggerated; on the contrary, the

girl had suppressed many disagreeable facts concerning her

father's drunkenness and the destitution it had brought upon

the family. There were no provisions in the house; many

necessary articles of comfort had been sold for drink; the children

were crying, and trouble had made Mrs. Drake “down

sick.”

“Don't blame him too much,” the poor woman pleaded for her

husband. “He don't have these bad turns more than twice a

year; and when he is sober he is kind and industrious. Poor

man! he tries to resist the appetite; but it is a perfect mania

with him, when it comes. Then they will sell him drink at the

tavern, spite of all I can do or say.”

With cheerful and encouraging words, Margaret emptied her

basket.

“O, this is a great abundance!” exclaimed Mrs. Drake.

“Don't think of sending us anything more. Miss Doane was

here yesterday, and will be here again to-day; and she never

comes without bringing something that we need.”

“Has anybody else visited you?”

“Mrs. Merrivale honored us last evening,” — Mrs. Drake spoke

bitterly, — “but I dread her more than poverty. She is a good

woman enough, for aught I know; and I 'm sure she would not

see anybody in want. But when she comes here, she is so

patronizing! and then she preaches such long sermons! You

would think she was Queen of Sheba, and we the guiltiest

wretches in the world! She galls my pride so, that I can't help

trouble herself any more.”

“You are a little in the wrong, I am afraid,” said Margaret.

“Mrs. Merrivale does not mean to offend; and, really, she has a

benevolent heart.”

The visit to these poor people drew out the blind girl's sympathies,

and made her happier and stronger. She was now eager

to hear what Laura would say when Margaret told her where

they had been. The way home across the fields was not long,

and, after a pleasant walk, they arrived at the parsonage.

“Let us go in still!” whispered Alice.

Margaret smiled upon the whim, and led her companion softly

into the kitchen. But here a sight met her eye that struck her

with amazement.

“What are you doing, Laura?” she asked.

“O, Miss Murray!” exclaimed the guilty Laura, turning

white, “it is the first time — the only time!”

“Let me see,” said Margaret. She drew towards her little

Elmira, — a younger sister of Laura, — who had dodged behind

the pantry door at her approach, and examined the contents of a

tin pail she was endeavoring to put out of sight. “What is this?”

“Some sugar, and rice, and a little tea,” faltered Laura.

Margaret had naturally a quick temper; and now the fire

came into her eyes and cheeks as she held up the pail and looked

at the wretched girl.

“Take it,” said she, in a tremulous voice; “run home with it,

Elmira; you are welcome.”

“We only jest put 'em into the pail to — to see how they

would look — to see how heavy they was,” gasped the frightened

Elmira. “We was going to take 'em out again.”

“Don't tell a wrong story about it, sis,” Laura broke forth,

beginning to sob. “I was going to send them to my mother.

Elmy was to tell her that you sent 'em — for I felt sure you

would, if you had been here, and known how sick ma is. But I

had no right to take anything without asking you. I hope to die

if it an't the first time. It will kill me to have ma know of it.”

“Wait, Elmira,” said Margaret, shaken by a strong emotion.

She bent over the child and kissed her, bursting into tears.

“Never tell a wrong story again, my child, for anything; will

you?” The child said no, crying violently. “There! good-by.

Kiss me, if you love me. I love you, and hope you will

be always true and happy.”

Having sent Elmira away, Margaret turned and saw her sister

coming out of the sitting-room with her bonnet on.

“Only say you forgive me, and I will go too,” said Laura.

“I know you won't want me to stay after this; I know I have

done a wicked thing, and lost your confidence, as I deserve; but

say you forgive me, and the shame of having my mother know it

won't quite kill me.”

Margaret led the distressed Alice to a chair, and assured her,

in a low voice, that all would be well, then turned, weeping, and

took Laura lovingly by the hand.

“Tell me first that you forgive me for being angry.”

“I forgive you! I should not have blamed you if you had

beaten me out of the house. I could have forgiven ten times

more than that in you.”

“And I forgive you as freely as I hope to be forgiven for my

own sins,” said Margaret, putting her arms around the girl's

neck. “I forgive you, and love you still. I might have done

the same in your place, — or a great deal worse, perhaps. I

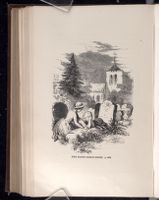

THE BLIND GIRL'S GRIEF. p. 483.

[Description: 731EAF. Illustration page. Image of a girl kneeling at a grave with her head in her hands. Another woman is trying to comfort her.]

cry any more about it. We will forget it all. You shall live

with us as before, and nobody shall ever know it — not even my

father or Junius: only Alice here, and she has a heart as full of

love and forgiveness as the sky is full of light.”

These words brought poor Laura to her knees; she bowed her

head and covered her face, and would not speak or rise till Margaret

lifted her up.

“I never heard anybody talk like that before!” she sobbed.

“I would n't have believed any one could. If I had been so good

to you as you have been to me, and you had stolen from me

then —”

“Perhaps you would not even have been angry, as I was at

first, Laura. We must bear with each other. And when we

pray, we will pray for charity, which is the dearest gift of God.

Come, my poor girl. It is all right now. And I have good

news for you. Your mother is better.”

“Have you been there? And were those things for her?”

“Yes, Laura; and I thank you for telling me how she was

situated. It has given Alice and me a good deal of happiness to

carry her relief.”

“O, what a wretch I am! I thought you did not understand

how poorly off she was, and that you was n't going to see her —

and I was too proud to ask you — so, as Elmy could n't get any

berries, — they are all gone from the hill, — I thought I would

give her something in their place. O, if you can forgive me, I 'll

be so glad to stay! and there is nothing I won't do for you!”

“You shall stay, Laura, and you shall have a quarter of a

dollar per week more than I have been giving you. I have

thought for a good while that I did not pay you enough.”

“I shan't take any more,” cried Laura, quickly. “You pay

me as much as Mrs. Merrivale paid me, and your work an't half

so hard, — and I 'd rather work for you for nothing than work

for her for a dollar a day.”

“But I shall pay what I think you earn, notwithstanding,”

returned Margaret, with a smile.

“You have given me time to sew for myself, and let me read,

odd spells, besides teaching me how to play the accordeon —”

“And now, make haste and get dinner, then you shall have

the afternoon to visit your mother, and help her about her work.

Let this seal our bond of union,” — Margaret kissed her, — “and

we will henceforth be the best friends in the world.”

With what joyful alacrity Laura resumed her work! Never

before had her heart beat half so light and happy.

“O, dear, dear, dear! If I could only be so good as you

are!” exclaimed Alice, clinging to Margaret's neck, as soon as

they were alone. “You have made me so full — so full! And

dear Laura — how much more I love her now!”

The blind girl felt a deep sympathy in the experience of Colonel

Merrivale's consumptive son, and at one time she often

enjoyed his society at the parsonage. But during the sultry

weather of August, he failed rapidly, and when the child, suffering

from wounds of grief still fresh, needed him most, he was

unable to come and see her. Then Junius and Margaret used

frequently to take her up to Summer Hill, and let her sit upon

her favorite stool at the feet of the dying boy, and talk with him

about the spiritual life.

One day, when Alice, as she assured Margaret, felt “pretty

smart,” the two set out on foot to pay their accustomed visit to

the invalid John. They went by the way of the burying-ground,

the spot where her weary father had so lately been laid to rest in

the quiet ground. Alice felt of the grave with her hands,

measured its length and breadth, as she had done so many times

before, then, laying her cheek on the turf, wept for a long while in

silence.

“Why do you always choose that spot to lay your head?”

“I think his heart must be here,” replied the child. “O, he

had such a good heart! It seems to me I can almost hear it

throb. Dear, dear father!” she murmured, embracing the grave,

“do love your blind girl a little!”

“You know, dear child,” said Margaret, kneeling by her side,

“your father is not here in the ground. He is in a brighter

country, just above ours.”

“I know it; for I see him in my dreams; but it is as if the

dear clothes he used to wear lay under this sod, and could hear

what I say.”

“You see him in your dreams?”

“O, yes, when I dream awake. He comes to me, and talks to

me as he used to. He is sad yet, for something seems to hold him

to the past — it is memory, I think. He was good, and loved

God, and I am sure he has gone to heaven; but people don't go

at once to the happiest place, do they?”

The child spoke with great earnestness, and Margaret comforted

her with a thoughtful answer.

“Nature delights in growth and gradual development. Death is

only a change of scene and circumstance to the soul. It enters the

other world as it leaves this; but there it finds a better soil to

grow in, and I think no clouds come to intercept the sunshine of

God's love. The best and purest of us here can only hope to

joyful and glorious progression we may make!”

“O, if we could always see these things as clearly!” said

Alice. “Only love and goodness make us truly happy; and it

seems to me that when our hearts are right, we enter heaven

here.”

In a little while the child asked to be led to the grave of Margaret's

mother, which was not far off. There the grass was

wilder and longer, and the flowers planted there had bloomed and

shed their tiny seeds through the circles of four revolving years.

“I wonder,” whispered Alice, putting her face in the grass, and

clasping Margaret's hand with a sudden impulse — “I wonder if

your mother knows my mother, in the spirit world! They would

love each other, I am sure! Don't tell any one, but I have seen

them together more than once. The last time was when you

prayed with me, night before last. They had their arms around

each other, and my mother held a basket of flowers, while your

mother scattered them all over and around us. I never saw

anything so bright and happy as their faces were.”

When Margaret thought her companion was sufficiently rested,

so that she could finish the excursion without fatigue, they left

the burying-ground; and not long after the blind girl's feet trod

the pleasant walks of Summer Hill. In the garden they met

Louise, whose eyes showed traces of recent tears.

“O, nothing new,” cried the young lady, when Margaret asked

what ailed her. “It 's the same old story. I don't see a happy

hour in the twenty-four.”

“So near your marriage, too?” said Margaret, seriously.

“Somehow, it don't make me happy to think of that. There

is something here that keeps swelling up — swelling up” — Louise

— “and nothing but death will ever put it down. Every day I

wish I was dead. I shall see no peace until I am.”

“At your age!” returned Margaret, sadly. “O, Louise, my

dear girl, there is something wrong.”

“It is all wrong. Nothing has been right with me since the

day I was born. O, dear, Margaret! you don't know anything

about it! There! I have said all I shall say. Go in and talk

with John; he will be glad to see you.”

“How is he to-day?”

“No better. He will be with us only a little while,” said

Louise, calmly. “I don't grieve for him — I shall not. I think

he is fortunate. I only wish I was in his place — as peaceful

and happy, going into my grave! Come in. Are you well to-day,

Alice?”

“Pretty well,” said the pensive child, in a voice so low as to

be scarcely audible.

They found John sitting in an easy-chair, with pillows at his

back — his father by his side reading to him. His pale face

lighted up with pleasure at sight of his friends; he took a holy

kiss from Margaret, and gave one as pure to her blind companion;

then the colonel abandoned his seat to the former, while Louise

brought the favorite stool for Alice to sit upon at the sick boy's

feet.

“What strange books John makes me read to him!” said the

colonel, placing a volume in Margaret's hand. “This is all

about spirits, divine law, compensation, and the grandeur of the

soul. It is one Junius loaned him. He goes into ecstacies over

it; although, I must confess, the writer's wisdom is often nonsense

to me.”

“To me it is clear as sunshine!” cried John.

“I suppose I have owl's eyes; I cannot endure the pure light,”

returned the colonel, as he left the room. He spoke with apparent

cheerfulness; but the moment he was alone, his face contracted

with grief, and he went into his chamber to weep, because all his

ambition, love and wealth could not save that son from death.

“It is four days since you have been here,” then said John to

the visitors, with touching pathos. “I want you to come oftener,

— if you like to; for I shall be here only a little while longer.”

“You know that I like to come, John,” answered Margaret,

with emotion. “And Alice — it does her good to feel your

sphere; she calls it seeing you; and indeed I think she sees you

better than most people do.”

“I hope she does; she is blind indeed if she does not,” said

John. “Few understand me; therefore few care to see me, and

there are very few I care to see.”

“You, and Alice, and Junius are his favorites,” remarked

Louise. “As for me, I don't think I should be missed if I

never came near him.”

“You know it is not so,” cried John, with an expression of

pain. “It is true, I find fault with you very often; but it is

because I feel all your irritations when you come near me, and I

would have you pluck out those thorns and bury them.”

“If I would, there is some one to drive them in again, as you

know. O, John!” — Louise wept upon his neck, — “I shall

remember all you have said to me. Some day it may do me

good. But now it only burns me.”

“My sister! my sister!” said John, in a choked voice, with

his affectionate arms around her neck — “God bless you! God

bless you!”

He could say no more, and the two wept together. They were

interrupted by Mrs. Merrivale, who, entering the room with her

usual energy of movement, came upon them before Louise could

disengage herself from her brother's embrace.

“Louise, I want to speak with you,” she said, scarcely observing

the presence of Margaret and Alice.

“I might have expected you about this time,” replied the

daughter, sourly, following her to another room.

“Why do you conduct with John in this way?” Mrs. Merrivale

demanded, censoriously. “Don't you see you make him

low-spirited? Besides, you do yourself no good. You spoil

your beauty crying so much.”

“My beauty!” sneered Louise, with angry contempt. “I

hate it, as I hate everything else. It has been no friend to me.

I would cry it all into the dust, and be glad to, if that would cure

the heartache. It always makes me better to talk with John, —

and if I can cry with him, I take it as a good sign; it shows

that I am not altogether hardened and selfish, as I often think I

am.”

“I won't have it!” retorted the mother, with sharp determination.

“I promised Mr. Milburn that I would take care of

you.”

“Mr. Milburn? O, monstrous! You take care of me for

that man!” And Louise added a remark which might not have

sounded musically sweet to the ear of her future husband. Her

mother became his apologist; spoke soothingly of his faults; and

said she had the best assurance that he had repented. “Repented!”

echoed Louise, with a bitter laugh. “When that man

does repent, I think sackcloth and ashes, as they say, will be

scarce for a season.”

“If you think him so bad, how can you marry him?”

“What a question at this late day! You know that, hate him

as you will, there is a fascination about him you cannot resist. I

know I don't love him — but he has mesmerized me, and I go

and come at his bidding, whether I will or no.”

“It is well that you go and come at somebody's bidding! I

was not aware of the fact before.”

“The more I think of it,” Louise went on, as if she had not

heard her mother's remark, “the more I think the picture Alice

described the first time I saw her, referred to me, and tells a bitter

truth. As she sat dreaming in the corner, she suddenly cried

out as if frightened; and when Margaret asked her what the

matter was, she said she saw a beautiful serpent charming a bird,

which, after fluttering over his glittering crest for a long time,

came so near that he struck her with his fangs.”

“There!” exclaimed Mrs. Merrivale, “don't tell me any more

of that girl's crazy fancies. And now if you go back to John's

room, remember what I have said. I will send you to your aunt's

in Philadelphia, if I can't manage you at home.”

When Louise returned, John was relating to Margaret and

Alice some portion of his experience which he did not appear to

consider proper for his sister's ear.

“Don't stop so abruptly because I came,” said she. “I know

I don't understand you as well as they do; but what I cannot

comprehend I will not hear.”

“I was telling them of something I have seen,—not outwardly,

but inwardly,” answered John, in some embarrassment, for he felt

conscious that what he was about to say might sound idle to his

sister's ears. “As I had not finished, I will commence again. I

am willing you should hear it, if you will — only don't speak of

he added, with a sad smile. “Some months ago, when I

first began to feel and know what the spiritual life is, I could see,

whenever I closed my eyes, a star — right here,” — John pointed

to the centre of his forehead. “For days it was stationary, but

at length it began to move; I watched it anxiously; and it came

and rested over a spot where a young child was laid. From that

time I saw the star no more; but I could see the child whenever

I looked inwardly; and I watched its growth for weeks and

weeks, as I had watched the movements of the star before. It

grew up within me; — and now it has nearly arrived at the stature

of a man. This bodily frame appears but as a shell to it,

which is fast falling to pieces, as it expands and bursts it. In a

little while this new man will be set free. You know what it

means, Margaret?”

“And I do too!” cried Alice. “I see it all as you describe

it. How beautiful! how strange!”

“What does it mean?” asked Louise. “It takes a spiritual

perception to see such things, and I have none.”

“To me it has a deep significance,” responded Margaret, holding

John's hand, with glistening eyes. “The star was the star

of Bethlehem. The wise men of the east were in the intellect

that followed it. The child represented the birth of Christ in the

soul — then the development of spiritual life. How wonderful

it is,” she added, speaking with reverential softness, “that every

circumstance in our Saviour's life and death symbolizes a spiritual

truth! What was true of him must be true of our own souls, even

to the death and resurrection, before we can merit to be called by

his dear name. Is it not so, John?”

John's lips moved with a quivering motion, but no sound came

how deeply he sympathized in the sentiment she had expressed.

About this time Junius made his appearance, driving up the

avenue in the parson's buggy.

“I was afraid the walk would be too much for Alice,” said he,

entering the invalid's room. “But if I intrude, just send me

away.”

“Intrude!” echoed John, greeting his friend with womanly

tenderness. “Our circle is never quite complete without you.

You seem to be a part of myself.”

It was affecting to witness the meeting of those brother spirits.

John's bosom was stirred by a deep and happy emotion, and the

fine face of Junius shone with love and joy. A change came over

the latter when he turned and took the hand of Louise.

“Still the same,” said he, with a sad, searching look, as her

beautiful eyes met his.

“Still the same!” she answered, with a forced laugh. “I 'm

sorry the old style don't suit you. I 'll change it as soon as convenient.”

“Can't you do something for that girl, Junius?” asked John.

“She is tossed upon a sea of trouble; and I would that some

potent spirit would say to the storm — `Peace; be still.'”

“I might have done something for her once — as she knows,”

replied Junius, with playful tenderness, laying his arm about her

waist. “But it is too late now.”

“I am a perverse child; — that 's true enough. But I can't

help my disposition,” said Louise. “I know when you might

have done me good — but I would n't let you. What are you

dreaming about, Alice?”

“I saw a beautiful bird in a cage, beating its wings and tearing

but it pecked his fingers, and would not let him open the cage-door.

I am sure I don't know what it means.”

“We will leave Louise to find out if the figure has any reference

to her,” cried Junius, pointing a significant finger at the

young lady. “Come, girls, — are you ready? Good-by,

Louise.”

His manner changed again as he turned from her, and bending

affectionately over John, kissed him, as if he had been a dear

sister. “The Lord love you, John!” said he. “It is the best

wish I have for my best beloved. Good-by.”

| XXIX.

OTHER CHANGES. Martin Merrivale | ||