49. CHAPTER XLIX.

PUCCOON IS LOST.

Puccoon was hunting deer on that night—the night of the snowstorm

one month before—through which Harley had ridden from

Blandfield—through which the vagrants had groped with their

lantern—through which the poor, thin figure of a woman of

twenty-eight had tottered, ever fainter, into the forests of the

Blackwater.

Puccoon was hunting by torch-light, as usual, but had seen

nothing. The snow had not begun to fall when he left his cabin.

In fact nothing could have been less to be suspected.

A mile from his cabin, however, and deep in the swamp, he had

felt a flake fall upon his hand. He looked up. It was snowing,

and the appearance of the sky indicated to his practiced eye that

the snowfall would probably be heavy.

Having realized this fact, Puccoon debated in his mind whether

or not he should return home.

“No,” he grunted, “not empty-handed. The snow's all the better.

They will see the light further. The very night to hunt.”

He went on, making a circle, and looking out.

Not a sound—not a pair of eyes, shining in the light of his torch.

Two hours afterward, he had no better fortune. He then fell

into a bad humor, maligned the deer, and determined to go back

home and take care of Fanny, who might be uneasy, he thought, at

his absence on such a night.

He vented his ill-humor, for want of something better, on the

“lightwood” torch which he carried.

“You can't find me any deer, and I don't want you, or mean to

be troubled with you!” said Puccoon—“blast you!”

This relieved him. He hurled the torch to the ground and put

his heel on it.

“I know my way without you!”

With which boast Puccoon strode along, his gun in his right

hand, his shoulders stooping, hunter-wise, his eyes peering into

the darkness. The snow was falling in a slow, dense mass—a

white wall shutting out every landmark.

When Puccoon had gone half-a-mile, tramping steadily through

the snow, he stopped and looked around him. After which he

began to laugh—a laugh of huge disdain and self-contempt.

“I'm lost!” he said.

This statement evidently struck him as involving an utter

absurdity.

“Lost!” he repeated, in the same tone.

He set forward again — the snow falling more and more densely.

The night was quite dark. He stumbled at times, and looked

about him. He could not see fifty feet.

The snow glared, and was some help. He had some assurance,

at least, that he would not fall into a ravine or pit.

“Heavy!” he muttered.

He looked in front and saw a sort of mound.

“Drifting, I should say, if there was any wind.”

More and more disgusted, Puccoon walked on, not diverging

from his path for the drift. He reached it—was about to plunge

through it—when the drift resisted. Something moaned as his

foot struck it.

At this sound Puccoon suddenly stopped—retreating a step. The

snow-drift moved, and another moan, the feeblest of moans, came

from it.

Puccoon's startled eyes measured the drift, taking in its shape.

It was long, and had the appearance of a corpse in a shroud.

“It is—something—alive!” exclaimed the trapper.

A moment afterwards he had stooped, groped in the long white

shroud, and dragged up the poor woman who had sunk there an

hour before.

Puccoon was a rough and informal human being, as far as his

manners went, but his face flushed suddenly with pity.

“A woman!” he exclaimed, in a voice faltering, and full of wonder,

“a woman freezing to death!—and I've lost my way! If I

only had my rum-flask!”

By ill-fortune he had left it at home.

“I must go the quicker!”

Having said this, Puccoon raised the body of the woman in his

arms, felt that her heart was still beating, and—full of new strength

and resolution now—carried her rapidly in the direction in which

he supposed his cabin to be.

He did not know the way, but for some time he had heard running

water. What water was it? There were many confluents of

the Blackwater.

He went on, bravely plunging through the snow. The path

seemed endless; the half dead woman seemed about to die in his

arms.

“I must find it!” exclaimed Puccoon.

He carried her to a spot where a broad-boughed laurel protected

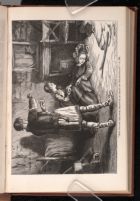

[ILLUSTRATION]

"They placed the poor creature in front of the fireplace."—P. 203.

[Description: 513EAF. Image of Puccoon and Fanny caring for the Lady of the Snow. Puccoon is pouring alcohol into a cup for the Lady to drink. Fanny is leaning over her trying to warm her hands. They have placed the Lady in front of the fireplace in their small cottage.]

her from the snow, and laid her down. Then he ran in the direction

of the water, reached it, recognized the banks of the Blackwater

half a mile above his hut, and, hastening back, took up his

burden again.

His course was now plain. He went on rapidly, struck into a

half-covered path which he knew, saw a light glimmer in the distance,

reached the hollow in which his hut stood, and running, out

of breath, up the hill, knocked loudly at the door, which was

opened by Fanny, pale and startled at the sight of her father, snow-covered,

and carrying what resembled a corpse in his arms.

A bright fire was blazing in the large fireplace, and in front of

this the poor creature was laid. Fanny excitedly chafed her hands,

and brushed the snow from her clothes, and Puccoon succeeded in

making her swallow some fiery rum. Under the influence of this

fire without and within, she opened her eyes, and a slight color

came to her cheeks.

“She's alive! She's alive!” shouted Puccoon, loudly.

The rough fellow then began to cry like a child.