| Mark Twain's (burlesque) autobiography and first romance | ||

1. A BURLESQUE

AUTOBIOGRAPHY.

TWO or three persons having at different

times intimated that if I would

write an autobiography they would read

it when they got leisure, I yield at last to this

frenzied public demand, and herewith tender

my history:

Ours is a noble old house, and stretches a

long way back into antiquity. The earliest ancestor

the Twains have any record of was a

friend of the family by the name of Higgins.

This was in the eleventh century, when our

people were living in Aberdeen, county of

Cork, England. Why it is that our long line

has ever since borne the maternal name (except

when one of them now and then took a playful

refuge in an alias to avert foolishness), instead

of Higgins, is a mystery which none of us has

vague, pretty romance, and we leave it alone.

All the old families do that way.

Arthour Twain was a man of considerable

note—a solicitor on the highway in William

Rufus' time. At about the age of thirty he

went to one of those fine old English places of

resort called Newgate, to see about something,

and never returned again. While there he died

suddenly.

Augustus Twain seems to have made something

of a stir about the year 1160. He was

as full of fun as he could be, and used to take

his old sabre and sharpen it up, and get in a

convenient place on a dark night, and stick it

through people as they went by, to see them

jump. He was a born humorist. But he got

to going too far with it; and the first time he

was found stripping one of these parties, the

authorities removed one end of him, and put it

up on a nice high place on Temple Bar, where

it could contemplate the people and have a

good time. He never liked any situation so

much or stuck to it so long.

Then for the next two hundred years the

The House That Jack Built.

[Description: 501EAF. Page 005. Image of a story title-page. In the center of the image is a human with an enlarged donkey head, dressed in suit and glasses, holding onto the front of a train car. In the background are men working on building a house.]

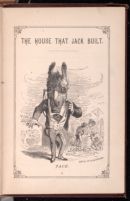

Our Family Tree

[Description: 501EAF. Page 006. Image of a scroll, curling at both ends. In the center is a gallows, with an owl perched on top and a man hanging from a noose. The caption at the bottom reads "our family tree".]noble, high-spirited fellows, who always went

into battle singing, right behind the army, and

always went out a-whooping, right ahead of it.

This is a scathing rebuke to old dead Froissart's

poor witticism that our family tree never

had but one limb to it, and that that one stuck

out at right angles, and bore fruit winter and

summer.

Early in the fifteenth century we have Beau

Twain, called “the Scholar.” He wrote a beautiful,

beautiful hand. And he could imitate anybody's

hand so closely that it was enough to make

a person laugh his head off to see it. He had infinite

took a contract to break stone for a road, and the

roughness of the work spoiled his hand. Still,

he enjoyed life all the time he was in the stone

business, which, with inconsiderable intervals,

was some forty-two years. In fact, he died in

harness. During all those long years he gave

such satisfaction that he never was through

with one contract a week till government gave

him another. He was a perfect pet. And he

was always a favorite with his fellow-artists,

and was a conspicuous member of their benevolent

secret society, called the Chain Gang.

He always wore his hair short, had a preference

for striped clothes, and died lamented by

the government. He was a sore loss to his

country. For he was so regular.

Some years later we have the illustrious John

Morgan Twain. He came over to this country

with Columbus in 1492, as a passenger. He

appears to have been of a crusty, uncomfortable

disposition. He complained of the food all

the way over, and was always threatening to go

ashore unless there was a change. He wanted

fresh shad. Hardly a day passed over his head

his nose in the air, sneering about the commander,

and saying he did not believe Columbus

knew where he was going to or had ever

been there before. The memorable cry of

“Land ho!” thrilled every heart in the ship

but his. He gazed a while through a piece of

smoked glass at the penciled line lying on the

distant water, and then said: “Land be hanged,

—it's a raft!”

When this questionable passenger came on

board the ship, he brought nothing with him

but an old newspaper containing a handkerchief

marked “B. G.,” one cotton sock marked

“L. W. C.” one woollen one marked “D. F.”

and a night-shirt marked “O. M. R.” And yet

during the voyage he worried more about his

“trunk,” and gave himself more airs about it,

than all the rest of the passengers put together.

If the ship was “down by the head,” and would

not steer, he would go and move his “trunk”

further aft, and then watch the effect. If the

ship was “by the stern,” he would suggest to

Columbus to detail some men to “shift that

baggage.” In storms he had to be gagged, be

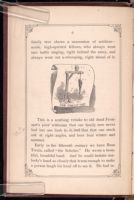

This is the House that Jack built.

[Description: 501EAF. Page 009. Image of large train depot, with ERIE on the front. There are three cavernous openings, out of which a train is leaving with smoke plumes pouring out of its stack.]

impossible for the men to hear the orders.

The man does not appear to have been openly

charged with any gravely unbecoming thing,

but it is noted in the ship's log as a “curious

circumstance” that albeit he brought his baggage

on board the ship in a newspaper, he took

it ashore in four trunks, a queensware crate, and

a couple of champagne baskets. But when he

came back insinuating in an insolent, swaggering

way, that some of his things were missing,

and was going to search the other passengers'

baggage, it was too much, and they threw him

overboard. They watched long and wonderingly

for him to come up, but not even a bubble

rose on the quietly ebbing tide. But while

every one was most absorbed in gazing over the

side, and the interest was momentarily increasing,

it was observed with consternation that the

vessel was adrift and the anchor cable hanging

limp from the bow. Then in the ship's dimmed

and ancient log we find this quaint note:

“In time it was discouvered yt ye troblesome passenger

hadde gonne downe and got ye anchor, and toke ye same and

solde it to ye dam sauvages from ye interior, saying yt he hadde

founde it ye sonne of a ghun!”

Yet this ancestor had good and noble instincts,

and it is with pride that we call to

mind the fact that he was the first white person

who ever interested himself in the work of

elevating and civilizing our Indians. He built

a commodious jail and put up a gallows, and to

his dying day he claimed with satisfaction that

he had had a more restraining and elevating

influence on the Indians than any other reformer

that ever labored among them. At this

point the chronicle becomes less frank and

chatty, and closes abruptly by saying that the

old voyager went to see his gallows perform

on the first white man ever hanged in America,

and while there received injuries which terminated

in his death.

The great grandson of the “Reformer” flourished

in sixteen hundred and something, and

was known in our annals as “the old Admiral,”

though in history he had other titles. He was

long in command of fleets of swift vessels, well

armed and manned, and did great service in

hurrying up merchantmen. Vessels which he

followed and kept his eagle eye on, always made

good fair time across the ocean. But if a ship

would grow till he could contain himself

no longer—and then he would take that

ship home where he lived and keep it there

carefully, expecting the owners to come for it,

but they never did. And he would try to get

the idleness and sloth out of the sailors of that

ship by compelling them to take invigorating

exercise and a bath. He called it “walking a

plank.” All the pupils liked it. At any rate,

they never found any fault with it after trying

it. When the owners were late coming for their

ships, the Admiral always burned them, so that

the insurance money should not be lost. At

last this fine old tar was cut down in the fulness

of his years and honors. And to her dying

day, his poor heart-broken widow believed that

if he had been cut down fifteen minutes sooner

he might have been resuscitated.

Charles Henry Twain lived during the latter

part of the seventeenth century, and was a zealous

and distinguished missionary. He converted

sixteen thousand South Sea islanders, and taught

them that a dog-tooth necklace and a pair of

spectacles was not enough clothing to come to

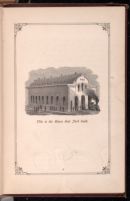

This is the Malt that lay in the

House that Jack built.

[Description: 501EAF. Page 013. Image of sacks of money. Each sack is humanized with smiling faces.]

very, very dearly; and when his funeral was

over, they got up in a body (and came out of

the restaurant) with tears in their eyes, and

saying, one to another, that he was a good

tender missionary, and they wished they had

some more of him.

Pah-go-to-wah-wah-pukketekeewis (Mighty-Hunter-with-a-Hog-Eye)

Twain adorned the

middle of the eighteenth century, and aided

Gen. Braddock with all his heart to resist the

oppressor Washington. It was this ancestor

who fired seventeen times at our Washington

from behind a tree. So far the beautiful romantic

narrative in the moral story-books is correct;

but when that narrative goes on to say

that at the seventeenth round the awe-stricken

savage said solemnly that that man was being

reserved by the Great Spirit for some mighty

mission, and he dared not lift his sacrilegious

rifle against him again, the narrative seriously

impairs the integrity of history. What he did

say was:

“It ain't no (hic!) no use. 'At man's so drunk

he can't stan' still long enough for a man to hit

This is the Rat that ate the Malt that lay in the

House that Jack built.

[Description: 501EAF. Page 015. Image of a giant rat with a moustached man's head. The rat is dressed in the garb of an officer, complete with sword, and is feeding off the sacks of money. In the background are two buildings, one labeled harem and one opera.]

more am'nition on him!”

That was why he stopped at the seventeenth

round, and it was a good plain matter-of-fact

reason, too, and one that easily commends itself

to us by the eloquent, persuasive flavor of probability

there is about it.

I always enjoyed the story-book narrative, but

I felt a marring misgiving that every Indian at

Braddock's Defeat who fired at a soldier a

couple of times (two easily grows to seventeen

in a century), and missed him, jumped to the

conclusion that the Great Spirit was reserving

that soldier for some grand mission; and so I

somehow feared that the only reason why

Washington's case is remembered and the

others forgotten is, that in his the prophecy

came true, and in that of the others it didn't.

There are not books enough on earth to contain

the record of the prophecies Indians and

other unauthorized parties have made; but one

may carry in his overcoat pockets the record

of all the prophecies that have been fulfilled.

I will remark here, in passing, that certain

ancestors of mine are so thoroughly well known

it to be worth while to dwell upon them, or

even mention them in the order of their birth.

Among these may be mentioned Richard

Brinsley Twain, alias Guy Fawkes; John

Wentworth Twain, alias Sixteen-String Jack;

William Hogarth Twain, alias Jack Sheppard;

Ananias Twain, alias Baron Munchausen; John

George Twain, alias Capt. Kydd; and then

there are George Francis Train, Tom Pepper,

Nebuchadnezzar and Baalam's Ass—they all

belong to our family, but to a branch of it

somewhat distantly removed from the honorable

direct line—in fact, a collateral branch, whose

members chiefly differ from the ancient stock

in that, in order to acquire the notoriety we

have always yearned and hungered for, they

have got into a low way of going to jail instead

of getting hanged.

It is not well, when writing an autobiography,

to follow your ancestry down too close to your

own time—it is safest to speak only vaguely of

your great-grandfather, and then skip from there

to yourself, which I now do.

I was born without teeth—and there Richard

without a humpback, likewise, and there I had

the advantage of him. My parents were neither

very poor nor conspicuously honest.

But now a thought occurs to me. My own

history would really seem so tame contrasted

with that of my ancestors, that it is simply wisdom

to leave it unwritten until I am hanged.

If some other biographies I have read had

stopped with the ancestry until a like event

occurred, it would have been a felicitous thing

for the reading public. How does it strike

you?

| Mark Twain's (burlesque) autobiography and first romance | ||