| SUPERSTITIONS OF THE ABBEY. The Crayon miscellany | ||

SUPERSTITIONS OF THE ABBEY.

The anecdotes I had heard of the quondam

housekeeper of Lord Byron, rendered me desirous

of paying her a visit. I rode in company

with Colonel Wildman, therefore, to the cottage

of her son William, where she resides, and found

her seated by her fireside, with a favourite cat

perched upon her shoulder and purring in her

ear. Nanny Smith is a large good looking woman,

a specimen of the old fashioned country

housewife, combining antiquated notions and

prejudices, and very limited information, with

natural good sense. She loves to gossip about

the Abbey and Lord Byron, and was soon drawn

into a course of anecdotes, though mostly of an

humble kind, such as suited the meridian of the

housekeeper's room and servants' hall. She

seemed to entertain a kind recollection of Lord

Byron, though she had evidently been much perplexed

by some of his vagaries; and especially

by the means he adopted to counteract his tendency

to corpulency. He used various modes

to sweat himself down; sometimes he would lie

for a long time in a warm bath, sometimes he

and loaded with great coats; “a sad toil for the

poor youth,” added Nanny, “he being so lame.”

His meals were scanty and irregular, consisting

of dishes which Nanny seemed to hold in

great contempt, such as pilaw, maccaroni, and

light puddings.

She contradicted the report of the licentious

life which he was reported to lead at the Abbey,

and of the paramours said to have been brought

with him from London. “A great part of his

time used to be passed lying on a sopha reading.

Sometimes he had young gentlemen of his acquaintance

with him, and they played some mad

pranks; but nothing but what young gentlemen

may do, and no harm done.”

“Once, it is true,” she added, “he had with

him a beautiful boy as a page, which the house

maids said was a girl. For my part, I know

nothing about it. Poor soul, he was so lame he

could not go out much with the men; all the

comfort he had was to be a little with the lasses.

The housemaids, however, were very jealous;

one of them, in particular, took the matter in

great dudgeon. Her name was Lucy; she was

a great favourite with Lord Byron, and had been

much noticed by him, and began to have high

notions. She had her fortune told by a man

who squinted, to whom she gave two and sixpence.

look high, for she would come to great things.

Upon this,” added Nanny, “the poor thing dreamt

of nothing less than becoming a lady, and mistress

of the Abbey; and promised me, if such

luck should happen to her, she would be a good

friend to me. Ah well-a-day! Lucy never had

the fine fortune she dreamt of; but she had better

than I thought for; she is now married, and

keeps a public house at Warwick.”

Finding that we listened to her with great attention,

Nanny Smith went on with her gossiping.

“One time,” said she, “Lord Byron took

a notion that there was a deal of money buried

about the Abbey by the monks in old times,

and nothing would serve him but he must have

the flagging taken up in the cloisters; and they

digged and digged, but found nothing but stone

coffins full of bones. Then he must needs have

one of the coffins put in one end of the great

hall, so that the servants were afraid to go there

of nights. Several of the sculls were cleaned

and put in frames in his room. I used to have

to go into the room at night to shut the windows,

and if I glanced an eye at them, they all seemed

to grin; which I believe sculls always do. I

can't say but I was glad to get out of the room.

“There was at one time (and for that matter

there is still) a good deal said about ghosts haunting

she saw two standing in a dark part of the cloisters

just opposite the chapel, and one in the garden,

by the lord's well. Then there was a young

lady, a cousin of Lord Byron, who was staying

in the Abbey and slept in the room next the

clock; and she told me that one night when she

was lying in bed, she saw a lady in white come

out of the wall on one side of the room, and go

into the wall on the opposite side.

“Lord Byron one day said to me, `Nanny,

what nonsense they tell about ghosts, as if there

ever were any such things. I have never seen

any thing of the kind about the Abbey, and I

warrant you have not.' This was all done, do

you see, to draw me out; but I said nothing, but

shook my head. However, they say his lordship

did once see something. It was in the great

hall—something all black and hairy: he said it

was the devil.

“For my part,” continued Nanny Smith, “I

never saw any thing of the kind—but I heard

something once. I was one evening scrubbing

the floor of the little dining room at the end of

the long gallery; it was after dark; I expected

every moment to be called to tea, but wished to

finish what I was about. All at once I heard

heavy footsteps in the great hall. They sounded

like the tramp of a horse. I took the light and

come from the lower end of the hall to the fireplace

in the centre, where they stopped: but I

could see nothing. I returned to my work, and

in a little time heard the same noise again. I

went again with the light; the footsteps stopped

by the fireplace as before; still I could see nothing.

I returned to my work, when I heard

the steps for a third time. I then went into the

hall without a light, but they stopped just the

same, by the fireplace half way up the hall. I

thought this rather odd, but returned to my work.

When it was finished, I took the light and went

through the hall, as that was my way to the

kitchen. I heard no more footsteps, and thought

no more of the matter, when, on coming to the

lower end of the hall, I found the door locked,

and then on one side of the door, I saw the

stone coffin with the scull and bones that had

been digged up in the cloisters.”

Here Nanny paused: I asked her if she believed

that the mysterious footsteps had any connexion

with the skeleton in the coffin; but she

shook her head, and would not commit herself.

We took our leave of the good old dame shortly

after, and the story she had related gave subject

for conversation on our ride homeward. It was

evident she had spoken the truth as to what she

had heard, but had been deceived by some peculiar

about a huge irregular edifice of the kind in a

very deceptive manner; footsteps are prolonged

and reverberated by the vaulted cloisters and

echoing halls; the creaking and slamming of

distant gates, the rushing of the blast through

the groves and among the ruined arches of the

chapel, have all a strangely delusive effect at

night.

Colonel Wildman gave an instance of the kind

from his own experience. Not long after he

had taken up his residence at the Abbey, he

heard one moonlight night a noise as if a carriage

was passing at a distance. He opened the

window and leaned out. It then seemed as if

the great iron roller was dragged along the gravel

walks and terrace, but there was nothing to

be seen. When he saw the gardener on the

following morning, he questioned him about

working so late at night. The gardener declared

that no one had been at work, and the roller was

chained up. He was sent to examine it, and

came back with a countenance full of surprise.

The roller had been moved in the night, but he

declared no mortal hand could have moved it.

“Well,” replied the Colonel good humouredly,

“I am glad to find I have a brownie to work

for me.”

Lord Byron did much to foster and give currency

the Abbey, by believing, or pretending to believe

in them. Many have supposed that his mind

was really tinged with superstition, and that this

innate infirmity was increased by passing much

of his time in a lonely way, about the empty

halls and cloisters of the Abbey, then in a ruinous

melancholy state, and brooding over the

sculls and effigies of its former inmates. I should

rather think that he found poetical enjoyment in

these supernatural themes, and that his imagination

delighted to people this gloomy and romantic

pile with all kinds of shadowy inhabitants.

Certain it is, the aspect of the mansion under

the varying influence of twilight and moonlight,

and cloud and sunshine operating upon its halls,

and galleries, and monkish cloisters, is enough

to breed all kinds of fancies in the minds of its

inmates, especially if poetically or stuperstitiously

inclined.

I have already mentioned some of the fabled

visitants of the Abbey. The goblin friar, however,

is the one to whom Lord Byron has given

the greatest importance. It walked the cloisters

by night, and sometimes glimpses of it were

seen in other parts of the Abbey. Its appearance

was said to portend some impending evil

to the master of the mansion. Lord Byron pretended

to have seen it about a month before he

He has embodied this tradition in the following

ballad, in which he represents the friar as

one of the ancient inmates of the Abbey, maintaining

by night a kind of spectral possession of

it, in right of the fraternity. Other traditions,

however, represent him as one of the friars

doomed to wander about the place in atonement

for his crimes. But to the ballad—

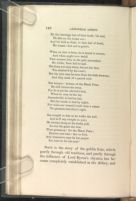

Who sitteth by Norman stone,

For he mutters his prayer in the midnight air,

And his mass of the days that are gone.

When the Lord of the Hill, Amundeville,

Made Norman Church his prey,

And expell'd the friars, one friar still

Would not be driven away.

Though he came in his might, with King Henry's right,

To turn church lands to lay,

With sword in hand, and torch to light

Their walls, if they said nay,

A monk remain'd, unchased, unchain'd,

And he did not seem form'd of clay,

For he's seen in the porch, and he's seen in the church,

Though he is not seen by day.

And whether for good, or whether for ill,

It is not mine to say;

But still to the house of Amundeville

He abideth night and day.

He flits on the bridal eve;

And 'tis held as faith, to their bed of death,

He comes—but not to grieve.

When an heir is born, he is heard to mourn,

And when aught is to befall

That ancient line, in the pale moonshine

He walks, from hall to hall.

His form you may trace, but not his face,

'Tis shadow'd by his cowl;

But his eyes may be seen from the folds between,

And they seem of a parted soul.

But beware! beware of the Black Friar,

He still retains his away,

For he is yet the church's heir,

Whoever may be the lay.

Amundeville is lord by day,

But the monk is lord by night,

Nor wine nor wassail could raise a vassal

To question that friar's right.

Say nought to him as he walks the hall,

And he'll say nought to you;

He sweeps along in his dusky pall,

As o'er the grass the dew.

Then gramercy! for the Black Friar;

Heaven sain him! fair or foul,

And whatsoe'er may be his prayer

Let ours be for his soul.”

Such is the story of the goblin friar, which,

partly through old tradition, and partly through

the influence of Lord Byron's rhymes, has become

completely established in the Abbey, and

edifice shall endure. Various visiters have

either fancied, or pretended to have seen him,

and a cousin of Lord Byron, Miss Sally Parkins,

is even said to have made a sketch of him from

memory. As to the servants at the Abbey, they

have become possessed with all kinds of superstitious

fancies. The long corridors and gothic

halls, with their ancient portraits and dark figures

in armour, are all haunted regions to them; they

even fear to sleep alone, and will scarce venture

at night on any distant errand about the Abbey

unless they go in couples.

Even the magnificent chamber in which I

was lodged was subject to the supernatural influences

which reigned over the Abbey, and

was said to be haunted by “Sir John Byron the

Little with the great Beard.” The ancient black

looking portrait of this family worthy, which

hangs over the door of the great saloon, was

said to descend occasionally at midnight from

the frame, and walk the rounds of the state

apartments. Nay, his visitations were not confined

to the night, for a young lady, on a visit to

the Abbey some years since, declared that, on

passing in broad day by the door of the identical

chamber I have described, which stood partly

open, she saw Sir John Byron the Little seated

by the fireplace, reading out of a great

some have been led to suppose that the story of

Sir John Byron may be in some measure connected

with the mysterious sculptures of the

chimney piece already mentioned; but this has

no countenance from the most authentic antiquarians

of the Abbey.

For my own part, the moment I learned the

wonderful stories and strange suppositions connected

with my apartment, it became an imaginary

realm to me. As I lay in bed at night and

gazed at the mysterious panel work, where gothic

knight, and Christian dame, and Paynim lover

gazed upon me in effigy, I used to weave a thousand

fancies concerning them. The great figures

in the tapestry, also, were almost animated by

the workings of my imagination, and the Vandyke

portraits of the cavalier and lady that

looked down with pale aspects from the wall,

had almost a spectral effect, from their immoveable

gaze and silent companionship—

Have something ghastly, desolate, and dread.

— Their buried looks still wave

Along the canvass; their eyes glance like dreams

On ours, as spars within some dusky cave,

But death is mingled in their shadowy beams.”

In this way I used to conjure up fictions of the

brain, and clothe the objects around me with

clock tolled midnight, I almost looked to see Sir

John Byron the Little with the long Beard stalk

into the room with his book under his arm, and

take his seat beside the mysterious chimney

piece.

| SUPERSTITIONS OF THE ABBEY. The Crayon miscellany | ||