Catlin's North American Indian portfolio. : Hunting scenes and amusements of the Rocky Mountains and prairies of America. : From drawings and notes of the author, made during eight years' travel amongst forty-eight of the wildest and most remote tribes of savages in North America. |

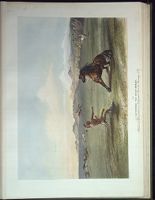

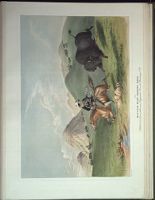

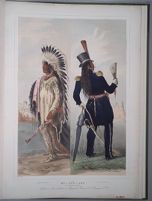

PLATE No. 25. |

| Catlin's North American Indian portfolio. : | ||

PLATE No. 25.

WI-JUN-JON. THE PIGEON'S EGG HEAD.

In offering this illustration to the reader, I am presenting to him a faithful delineation of the resemblance of an Assinneboin Warrior, in the flowing and classic costume of

his country, as he appeared on his way to the city of Washington, faithfully contrasted with the uncouth plight in which he returned to his tribe the next season, after one

year's teaching in the school of civilisation: and in the following narrative, a faithful account of its melancholy and fatal results.

Wi-jun-jon, the Pigeon's Egg Head, was a warrior of the Assinneboins, young, proud, handsome, valiant, and graceful. He had fought many a battle and won many laurels.

The numerous scalps from his enemies' heads adorned his dress, and his claims were fair and just for the highest honors that his country could bestow upon him, for his father

was head chief of the nation. This young Assinneboin, the Pigeon's Egg Head, was selected by Major Sanford, the Indian agent, to represent his tribe in a delegation which

visited Washington city under his charge, in the winter of 1832. With this gentleman the Assinneboin, together with representatives of several others of those North-western

tribes, descended the Missouri river several thousand miles on their way to Washington. While descending the river in a Mackinaw boat, from the mouth of the Yellow Stone,

Wi-jun-jon and another of his tribe who was with him, at their first approach to the civilized settlements, commenced a register of the white men's houses (or cabins) which they

passed, by cutting a notch for each on the side of a pipe-stem, in order to be able to show, when they should get home, how many white men's houses they had seen on their

journey. At first the cabins were scarce; but continually more and more rapidly increased in numbers as they advanced further down the river, by which means their pipe-stem

was soon filled with notches, when they resolved to cut the rest of them on the handle of a war club, which, to their great surprise, was soon filled also: at length, while the

boat was moored at the shore for the purpose of cooking the dinner for the party, Wi-jun-jon and his companion stepped into the bushes and cut a long stick, from which they

peeled the bark, and when the boat was again under weigh they sat down, and with much labor transferred the notches on to it from the pipe-stem and club, and also kept

adding a notch for every house they passed. This stick was also soon filled, and in a day or two, two or three others; when at last they seemed much at a loss to know

what to do with their troublesome records, until they came in sight of St. Louis, which is a town of 20,000 or 30,000 inhabitants, upon which unexpected occurrence, after

consulting a little, they pitched their sticks overboard into the river, leaving all further entries and records to those skilled in the use of pen, ink, and paper.

I was in St. Louis when they arrived, and painted their portraits while they rested in that place. Wi-jun-jon was the first who reluctantly yielded to the solicitations of

the Indian agent and myself, and appeared as sullen as death in my painting-room, with eyes fixed like those of a statue upon me, though his pride had plumed and tinted him

in all the freshness and brilliancy of an Indian's toilet. In his nature's uncowering pride he stood a perfect model; but superstition had hung a lingering curve upon his lip,

which pride had stiffened into contempt. He had been urged into a measure against which his fears had pleaded; yet he stood unmoved and unflinching amid the struggles of

mysteries that were hovering about him, foreboding ills of every kind, and misfortunes that were to happen to him in consequence of this operation.

He was dressed in his native costume, which was classic and exceedingly beautiful. His leggins and shirt were of the mountain goat skin, richly garnished with quills of

the porcupine, and fringed with locks of scalps taken from the heads of his enemies. Over these floated his long hair in plaits that fell nearly to the ground; his head was

decked with the war-eagle's plumes; his robe was of the skin of a young buffalo bull, richly garnished and emblazoned with the battles of his life; his quiver and bow were

slung, and his shield was made of the skin of the buffalo's neck. I painted him in this beautiful dress, as well as the others who were with him; and after I had done, Major

Sanford proceeded to Washington with them, where they spent the winter.

Wi-jun-jon was the foremost on all occasions—the first to enter the levee, the first to shake the President's hand, and make his speech to him; the last to extend the hand

to, but the first to catch the smiles and gain the admiration of the gentler sex. He travelled the giddy maze and beheld amidst the buzzing din of civil life the tricks of art,

the handiworks, and finery; he visited the principal cities, he saw the forts, the ships, the great guns, steamers, balloons, &c.; and in the spring returned to St. Louis, where I

joined him and his companions on their way back to their own country.

Through the politeness of Mr. Chouteau, of the American Fur Company, I was admitted (the only passenger except Major Sanford and his Indians) to a passage in the

steamboat, on her first trip to the Yellow Stone; and when I had embarked, and the steamer was about to start. Wi-jun-jon made his appearance on deck, in a full suit of

regimentals! In Washington he had exchanged his beautifully garnished and classic costume for a full dress "en militaire." It was, perhaps, presented to him by the President.

It was broadcloth, of the finest blue, trimmed with gold face; on his shoulders were mounted two immense epaulettes; his neck was strangling with a shining black stock; and

his feet were pinioned in a pair of waterproof boots, with high heels. On his head was a high-crowned beaver hat, with a broad silver-lace band, surmounted by a huge red

feather some two feet high; his coat collar, stiff with lace, came higher up than his cars, and over it flowed down towards his haunches his long Indian locks, glued up in rolls

and plaits with red paint. A large silver medal was suspended from his neck by a blue ribbon; and from his waist fell a wide belt, supporting by his wide a broadsword. He

had drawn a pair of white kid gloves on his hands, in one of which he held a blue umbrella, and in the other a large fan. In this fashion was poor Wi-jun-jon metamorphored,

mighty Missouri, and taking him to his native land again; where he was soon to light his pipe, and cheer the wigwam fireside with tales of novelty and wonder.

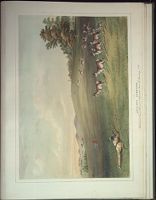

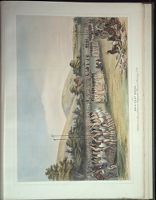

Not far from the mouth of the Yellow Stone River the steamer was moored by the side of an extensive and beautiful prairie, on which were encamped the whole of the

Assinneboin tribe, to the number of 8,000 or 10,000 souls, awaiting the arrival of the steamer, with their two warriors from Washington city; one of whom, unfortunately for

poor Wi-jun-jon, had died of the quinsey on his way home, leaving the marvellous recitals to be made by his companion, uncorroborated, and to be received by the tribe for just

as much as their superstitious credulity should deem them worth. When the steamer arrived opposite their encampment, Wi-jun-jon stepped ashore in the plight above named, with

a keg of whiskey under his arm, and the umbrella in his hand, and took a position on the bank amongst his friends—his parents—his wife and little children—from whom he had

been more than a year separated; not one of whom, for half an hour or more, exhibited the least symptoms of recognition, although every soul in the tribe knew well who was

before them. He also gazed upon them—upon his wife and little ones who were about—us if they were foreign to him, and he had not a feeling or a thought to interchange

with them. Thus the mutual gazings upon and from this would-be stranger lasted for full half an hour, when a gradual, but cold and exceedingly formal recognition began to

take place; and an acquaintance ensued, which ultimately and smoothly resolved itself, without the least apparent emotion, into its former state; and the mutual kindred intercourse

seemed to flow on exactly where it had broken off, as if it had been interrupted but for a moment, and nothing had transpired in the interim to check or change its character

or expression.

After Wi-jun-jon had reached his home, and thus passed the usual salutations among his friends, he commenced the simple narration of scenes he had passed through, and

of things he had beheld among the whites, which appeared to his people so much like fiction that it was impossible to believe it, and they set him down as an impostor. "He

has been (they said) among the whites, who are great liars, and all he has learned is to come home and tell lies." He sank rapidly into disgrace in his tribe; his high claims

to political eminence all vanished; he was reputed worthless—the greatest liar of his nation; the chiefs shunned him and passed him by, as one of the tribe who was lost; yet

the cars of the gossiping portion of the tribe were open, and the camp-fire circle and the wigwam fireside gave silent audience to the whispered narratives of the "travelled

Indian."

The next day after he had arrived among his friends the superfluous part of his coat (which was a laced frock) was converted into a pair of leggins for his wife, and his

hat-band of silver lace furnished her a magnificent pair of garters. The remnant of the coat, curtailed of its original length, was seen buttoned upon the shoulders of his brother,

over and above a pair of leggins of buckskin; and Wi-jun-jon was parading about among his gaping friends, with a bow and quiver slung over his shoulders, which, sans coat

exhibited a fine linen shirt with studs and sleeve buttons. His broadsword kept its place, but about noon his boots gave way to a pair of garnished mocasins; and in such

plight he gossiped away the day among his friends, while his heart spoke so freely and so effectually from the bung-hole of a keg of whiskey, which he had brought the whole

way (as one of the choicest presents made him at Washington), that his tongue became silent.

One of his little fair innmoratas, or "catch crumbs," such as live in the halo of most great men, fixed her eyes and her affections upon his beautiful silk braces; and the

next day, while the keg was yet dealing out its kindnesses, he was seen paying visits to the lodges of his old acquaintances, swaggering about, with his keg under his arm,

whistling "Yankee Doodle," and "Washington's Grand March;" his white shirt, or that part of it that had been flapping in the wind, had been shockingly tithed—his pantaloons

of blue were razeed into a pair of comfortable leggins; his bow and quiver were slung; and his broadsword, which trailed on the ground, had sought the centre of gravity, and

taken a position between his legs, and dragging behind him, served as a rudder to steer him over the `earth's troubled surface."

Two days' revel of this kind had drawn from his keg all its charms; and in the mellowness of his heart, all his finery had vanished, and all its appendages, except his

umbrella, to which his heart's best affections still clung, and with it and under it, in rude dress of buckskin, he was afterwards to be seen, in all sorts of weather, acting the fop

and the beau as well as he could with his limited means. In this plight, and in this dress, he began, in his sober moments, to entertain and instruct his people, by honest and

simple narratives of things and scenes he had beheld during his tour to the East; but which (unfortunately for him) were to them too marvellous and improbable to be believed.

He told the gaping multitude, that were constantly gathering about him, of the distance he had travelled—of the great number of houses he had seen—of the towns and cities,

with all their wealth and splendor—of travelling on steam-boats, in coaches, and on railroads. He described our forts and seventy-four gun ships, which he had visited; their big

guns; our great bridges; our large council-house at Washington, and its doings; the curious and wonderful machines in the Patent Office (which he pronounced the greatest

medicine place he had seen); he described the great war parade, which he saw in the city of New-York; the ascent of a balloon from Castle Garden; the surprising numbers

of the "Pale Faces," the beauty of their squaws; their red cheeks; and many thousands of other things, all of which were so much beyond their comprehension that they "could

not be true," and "he must be the greatest liar in the whole world."

But he was beginning to acquire a reputation of a different kind. He was denominated a medicine-man, and one, too, of the most extraordinary character; for they deemed

him far above the ordinary sort of human beings whose mind could invent and conjure up for their amusement such an ingenious fabrication of novelty and wonder. He steadily

and unostentatiously persisted, however, in this way of entertaining his friends and his people, though he knew his character was affected by it. He had an exhaustless theme to

descant upon, and he seemed satisfied to lecture all his life for the pleasure which it gave him. So great was his medicine, however, that they began, chiefs and all, to look

upon him as a most extraordinary being; and the customary honors and forms began to be applied to him, and the respect shown him, that belongs to all men in the Indian

country who are distinguished for their medicine or mysteries. In short, when all became familiar with the astonishing representations that he had made, and with the wonderful

alacrity with which "he created them," he was denominated the very greatest of medicine, and not only that, but the "lying medicine." That he should be the greatest of

medicine, and that for lying, merely, rendered him a prodigy in mysteries that commanded not only respect, but at length (when he was more maturely heard and listened to),

admiration, awe, and at last dread and terror; which altogether must needs conspire to rid the world of a monster, whose more than human talents must be cut down to less

than human measurement.

In this way the poor fellow had lived, and been for three years past continually relating the scenes he had beheld in his tour to the "Far East," until his medicine

became so alarmingly great, that they were unwilling he should live: they were disposed to kill him for a wizard. One of the young men of the tribe took the duty upon

himself, and after much perplexity hit upon the following plan: To wit.—He had fully resolved, in conjunction with others who were in the conspiracy, that the medicine of

Wi-jun-jon was too great for the ordinary mode, and that he was so great a liar that a bullet from his rifle, or an arrow from his bow, would not kill him. While the young

man was in this distressing dilemma, which lasted for some weeks, he had a dream one night which solved all his difficulties, and in consequence of which he loitered about the

store in the Fort, at the mouth of the Yellow Stone, until he could procure by stealth (according to the injunctions of his dream) the handle of an iron pot, which he supposed

to possess the requisite virtue, and taking it into the woods, he there spent a whole day in straightening and filing it to fit it into the barrel of his gun; after which he made

his appearance again in the Fort, with his gun under his robe, charged with the pot-handle, and getting behind poor Wi-jun-jon, whilst he was talking with the trader, placed the

muzzle behind his head and blew out his brains!

Thus ended the days and the greatness, and all the pride and hopes of Wi-jun-jon, the "Pigeon's Egg Head," a warrior and a brave of the valiant Assinneboins, who

travelled eight thousand miles to see the President, and the great cities of the civilized world; and who, for telling the truth and nothing but the truth, was, after he got home,

disgraced as a liar, and killed as an impostor.

THE END.

| Catlin's North American Indian portfolio. : | ||