| O-kee-pa, a religious ceremony, and other customs of the Mandans | ||

O-KEE-PA:

A RELIGIOUS CEREMONY OF THE MANDANS.

In a narrative of fourteen years' travels and residence amongst the

native tribes of North and South America, entitled `Life amongst

the Indians,' and published in London and in Paris, several years

since, I gave an account of the tribe of Mandans,—their personal

appearance, character, and habits; and briefly alluded to the singular

and unique custom which is now to be described, and was then

omitted, as was alleged, for want of sufficient space for its insertion,—

the "O-kee-pa," an annual religious ceremony, to the strict observance

of which those ignorant and superstitious people attributed not

only their enjoyment in life, but their very existence; for traditions,

their only history, instructed them in the belief that the singular

forms of this ceremony produced the buffalos for their supply of food,

and that the omission of this annual ceremony, with its sacrifices

made to the waters, would bring upon them a repetition of the

calamity which their traditions say once befell them, destroying the

whole human race, excepting one man, who landed from his canoe

on a high mountain in the West.

This tradition, however, was not peculiar to the Mandan tribe, for

amongst one hundred and twenty different tribes that I have visited in

related to me distinct or vague traditions of such a calamity, in which

one, or three, or eight persons were saved above the waters, on the top

of a high mountain. Some of these, at the base of the Rocky Mountains

and in the plains of Venezuela, and the Pampa del Sacramento

in South America, make annual pilgrimages to the fancied summits

where the antediluvian species were saved in canoes or otherwise,

and, under the mysterious regulations of their medicine (mystery)

men, tender their prayers and sacrifices to the Great Spirit, to ensure

their exemption from a similar catastrophe.

Indian traditions are generally conflicting, and soon run into

fable; but how strong a proof is the unanimous tradition of the

aboriginal races of a whole continent, of such an event!—how strong

a corroboration of the Mosaic account,—and what an unanswerable

proof that anthropos Americanus is an antediluvian race! And how

just a claim does it lay, with the various modes and forms which

these poor people practise in celebrating that event, to the inquiries

and sympathies of the philanthropic and Christian (as well as to

the scientific) world!

Some of those writers who have endeavoured to trace the aborigines

of America to an Asiatic or Egyptian origin, have advanced these traditions

as evidence in support of their theories, which are, as yet,

but unconfirmed hypotheses; and as there is not yet known to exist

(as I shall show, but not in this place), either in the American languages,

or in the Mexican or Aztec, or other monuments of these

people, one single proof of such an immigration (though it could have

been made), these traditions as yet are mine, and not theirs,—are

American,—indigenous, and not exotic. If it were shown that inspired

history of the Deluge and of the Creation restricted those events to

one continent alone, then it might be that the American races came

from the Eastern continent, bringing these traditions with them;

but until that is proved, the American traditions of the Deluge are

aborigines of America brought their traditions of the Deluge from

the East, why did they not bring inspired history of the Creation?

Though there is not a tribe in America but what have some

theory of man's creation, there is not one amongst them all that

bears the slightest resemblance to the Mosaic account. How strange

is this if these people came from the country where inspiration

was prior to all history! The Mandans believed they were created

under the ground, and that a portion of their people reside there

yet. The Choctaws assert that "they were created craw-fish, living

alternately under the ground and above it, as they chose; and

coming out at their little holes in the earth to get the warmth of

the sun one sunny day, a portion of the tribe was driven away

and could not return; they built the Choctaw village, and the remainder

of the tribe are still living under the ground."

The Sioux relate with great minuteness their traditions of the

creation. They say that "the Indians were all made from the red

pipe-stone, which is exactly of their colour; that the Great Spirit,

at a subsequent period, called all the tribes together at the red pipe-stone

quarry, and told them this, that the red stone was their flesh,

and that they must use it for their pipes only."

Other tribes were created under the water; and at least one half

of the tribes in America represent that man was first created under

the ground, or in the rocky caverns of the mountains. Why this

diversity of theories of the Creation, if these people brought their tradition

of the Deluge from the land of inspiration?

This interesting subject, too intricate for full discussion in this

work, will be further incidentally alluded to in the course of the

following relations.

For the scientific, who look amongst these native people chiefly

for shapes of their skulls and for analogies to foreign races, I believe

there will be found enough in the following description of their

philanthropic and religious world, whose motives are love and sympathy,

there will be sufficient to excite their profoundest astonishment,

and to touch their hearts with pity.

In a relation so singular, and apparently incredible, as I am now

to make, I hope the reader will be able to follow me, under the

conviction that I am representing nothing in my descriptions or in

my illustrations but what I saw, and that I had by my side, during

the four days of these scenes, three civilized and educated men,

who gave me their certificates that they witnessed with me all these

scenes as I have represented them, and which certificates, with other

evidences, will be produced in their proper places, as I proceed.

During the summer of 1832 I made two visits to the tribe of

Mandan Indians, all living in one village of earth-covered wigwams,

on the west bank of the Missouri river, eighteen hundred miles above

the town of St. Louis.

Their numbers at that time were between two and three thousand,

and they were living entirely according to their native modes,

having had no other civilized people residing amongst them or in

their vicinity, that we know of, than the few individuals conducting

the Missouri Fur Company's business with them, and living in a

trading-house by the side of them.

Two exploring parties had long before visited the Mandans, but

without in any way affecting their manners. The first of these, in

1738, under the lead of the Brothers Verendrye, Frenchmen, who

afterwards ascended the Missouri and Saskachewan, to the Rocky

Mountains; and the other, under Lewis and Clark, about sixty years

afterwards.

The Mandans, in their personal appearance, as well as in their

modes, had many peculiarities different from the other tribes

around them. In stature they were about the ordinary size; they

were comfortably, and in many instances very beautifully clad with

made of skins, and neatly embroidered with dyed porcupine quills.

Every man had his "tunique and manteau" of skins, which he wore

or not as the temperature prompted; and every woman wore a dress

of deer or antelope skins, covering the arms to the elbows, and the

person from the throat nearly to the feet.

In complexion, colour of hair, and eyes, they generally bore a

family resemblance to the rest of the American tribes, but there

were exceptions, constituting perhaps one-fifth or one sixth-part of

the tribe, whose complexions were nearly white, with hair of a

silvery-grey from childhood to old age, their eyes light blue, their

faces oval, devoid of the salient angles so strongly characterizing all

the other American tribes, and owing, unquestionably, to the infusion

of some foreign stock.

Amongst the men, practised by a considerable portion of them,

was a mode peculiar to the tribe, and exceedingly curious,—that of

cultivating the hair to fall, spreading over their backs, to their

haunches, and oftentimes as low as the calves of their legs; divided into

flattened masses of an inch or more in breadth, and filled at intervals

of two or three inches with hardened glue and red or yellow ochre.

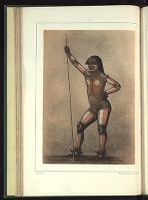

I here present (Plate I.) three of my Mandan portraits in their

ordinary costume,—a chief, a warrior, and a young woman,—lest

the reader should form a wrong opinion of their usual appearance,

from the bizarre effects of the figures disguised with clay and other

pigments in the ceremony to be described in this work.

The Mandans (Nu-mah-ká-kee, pheasants, as they called themselves)

have been known from the time of the first visits made to

them to the day of their destruction, as one of the most friendly and

hospitable tribes on the United States frontier; and it had become a

proverb in those regions, and much to their credit, as they claimed,

"that no Mandan ever killed a white man."

I was received with great kindness by their chiefs and by the

other designs and notes on their customs; and from Mr. J. Kipp,

the conductor of the Fur Company's affairs at that post, and his

interpreter, I was enabled to obtain the most complete interpretation

of chiefly all that I witnessed.

I had heard, long before I reached their village, of their "annual

religious ceremony," which the Mandans call "O-kee-pa," and from

Mr. Kipp, who had resided several years with the people, a partial

account of it; and from him the most pressing advice to remain

until the ceremony commenced, as he believed it would be a subject

of great interest to me.

I resolved to await its approach, and in the meantime, while inquiring

of one of the chiefs whose portrait I was painting, when this

ceremony was to begin, he replied that "it would commence as soon

as the willow-leaves were full grown under the bank of the river."

I asked him why the willow had anything to do with it, when he

again replied, "The twig which the bird brought into the Big Canoe

was a willow bough, and had full-grown leaves on it."

It will here be for the reader to appreciate the surprise with

which I met such a remark from the lips of a wild man in the heart

of an Indian country, and eighteen hundred miles from the nearest

civilization; and the eagerness with which I followed up my inquiries

on a subject so unexpected and so full of interest.

I inquired of him what bird he alluded to, which he found difficulty

in making me understand, and, taking me by the arm, he conducted

me through the winding avenues of the village until he discovered

a couple of mourning doves pecking in the side of one of the

earth-covered wigwams, and pointing to them said, "There is the

bird; it is great medicine." It then occurred to me that on my

arrival in their village Mr. Kipp had cautioned me against harming

these birds, which were numerous in the village, and guarded and protected

with a superstitious veneration as great medicine (or mystery).

The reader may here very properly inquire, If the American

traditions of the Deluge have not been brought from the Eastern

Continent, how is it that the Mandans have the Mosaic account of

the olive-branch and the dove? This is easily explained; for these

terms, and "Big Canoe," used by the Mandans, form no part of the

general traditions, being entirely unused by, and unknown to, the

other tribes of the American Continent; but have been introduced

amongst the Mandans, like other customs that will be described, by

some errant colony of Welsh, or other civilized people who have

merged into the Mandan tribe, and, having witnessed the Mandan

ceremonies, and heard their traditions of the Deluge, have described

to those people the Mosaic account, and from which the Mandans

have appropriated and introduced into their system the terms "willow

bough" for olive-branch, and "Big Canoe" for the Ark, whilst

all the other tribes which speak of a canoe use the word "canoe"

only. And there are yet many tribes in the vicinity of the Rocky

Mountains, and in the north of Mexico, which, without impairing in

the least the great fact of the tradition, make no mention of a canoe

whatever, but represent that the ancestor or ancestors of the present

human race, by various miraculous modes, which they describe,

gained the summit of a mountain above the reach of the waters in

which the rest of mankind perished.

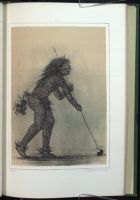

In Plate II. I have given a bird's-eye view of a section of the

Mandan village, which is necessary to enable the reader fully to

understand the ceremonies to be described.

As I have before said, these people all lived in one village, and

their wigwams were covered with earth,—they were all of one form;

the frames or shells constructed of timbers, and covered with a

thatching of willow-boughs, and over and on that, with a foot or two

in thickness, of a concrete of tough clay and gravel, which became

so hard as to admit the whole group of inmates, with their dogs, to

recline upon their tops. These wigwams varied in size from thirty

from twenty to thirty persons within.

The village was well protected in front by a high and precipitous

rocky bank of the river; and, in the rear, by a stockade of

timbers firmly set in the ground, with a ditch inside, not for water,

but for the protection of the warriors who occupied it when firing

their arrows between the pickets.

In this view the "Medicine Lodge," as it is termed, and the "Big

Canoe" (or symbol of the "Ark") are conspicuous, and their positions

should be borne in mind during the descriptions of the ceremonies

that are to be given.

The "Medicine Lodge," the largest in the village and seventy-five

feet in diameter, with four images (sacrifices of different-coloured

and costly cloths) suspended on poles above it, was considered by

these people as a sort of temple, held as strictly sacred, being built

and used solely for these four days' ceremonies, and closed during

the rest of the year.

In an open area in the centre of the village stands the Ark (or

"Big Canoe"), around which a great proportion of their ceremonies

were performed. This rude symbol, of eight or ten feet in height,

was constructed of planks and hoops, having somewhat the appearance

of a large hogshead standing on its end, and containing some

mysterious things which none but the medicine men were allowed to

examine. An evidence of the sacredness of this object was the fact

that though it had stood, no doubt for many years, in the midst and

very centre of the village population, there was not the slightest

discoverable bruise or scratch upon it!

In the distance in this view, and outside of the picket, is seen

a portion of their cemetery. Their dead, partially embalmed, are

tightly wrapped in buffalo hides, softened with glue and water, and

placed on slight scaffolds, above the reach of animals or human

hands, each body having its separate scaffold.

The O-kee-pa, though in many respects apparently so unlike it,

was strictly a religious ceremony, it having been conducted in most of

its parts with the solemnity of religious worship, with abstinence,

with sacrifices, and with prayer, whilst there were three other distinct

and ostensible objects for which it was held.

1st. As an annual celebration of the event of the "subsiding of

the waters" of the Deluge, of which they had a distinct tradition,

and which in their language they called "Mee-ne-ró-ka-há-sha" (the

settling down of the waters).

2nd. For the purpose of dancing what they called "Bel-lohk-na-pick

(the bull-dance), to the strict performance of which they attributed

the coming of buffalos to supply them with food during the

ensuing year.

3rd. For the purpose of conducting the young men who had

arrived at the age of manhood during the past year, through an

ordeal of privation and bodily torture, which, while it was supposed

to harden their muscles and prepare them for extreme endurance,

enabled their chiefs, who were spectators of the scene, to decide upon

their comparative bodily strength, and ability to endure the privations

and sufferings that often fall to the lot of Indian warriors,

and that they might decide who amongst the young men was the

best able to lead a war-party in an extreme exigency.

The season having arrived for the holding of these ceremonies,

the leading medicine (mystery) man of the tribe presented himself

on the top of a wigwam one morning before sunrise, and haranguing

the people told them that "he discovered something very strange in

the western horizon, and he believed that at the rising of the sun

a great white man would enter the village from the west and open

the Medicine Lodge."

In a few moments the tops of the wigwams, and all other elevations,

were covered with men, women, and children on the look-out;

and at the moment the rays of the sun shed their first light over the

and in a few minutes all voices were united in yells and mournful

cries, and with them the barking and howling of dogs; all were in

motion and apparent alarm, preparing their weapons and securing

their horses, as if an enemy were rushing on them to take them by

storm.

All eyes were at this time directed to the prairie, where, at the

distance of a mile or so from the village, a solitary human figure was

seen descending the prairie hills and approaching the village in a

straight line, until he reached the picket, where a formidable array

of shields and spears was ready to receive him. A large body of

warriors was drawn up in battle-array, when their leader advanced

and called out to the stranger to make his errand known, and to tell

from whence he came. He replied that he had come from the high

mountains in the west, where he resided,—that he had come for the

purpose of opening the Medicine Lodge of the Mandans, and that he

must have uninterrupted access to it, or certain destruction would

be the fate of the whole tribe.

The head chief and the council of chiefs, who were at that moment

assembled in the council-house, with their faces painted black,

were sent for, and soon made their appearance in a body at the

picket, and recognized the visitor as an old acquaintance, whom they

addressed as "Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah" (the first or only man). All

shook hands with him, and invited him within the picket. He then

harangued them for a few minutes, reminding them that every

human being on the surface of the earth had been destroyed by the

water excepting himself, who had landed on a high mountain in the

West, in his canoe, where he still resided, and from whence he had

come to open the Medicine Lodge, that the Mandans might celebrate

the subsiding of the waters and make the proper sacrifices to the

water, lest the same calamity should again happen to them.

The next moment he was seen entering the village under the

ceased, and orders were given by the chiefs that the women

and children should all be silent and retire within their wigwams,

and their dogs all to be muzzled during the whole of that day, which

belonged to the Great Spirit.

In the midst of this startling and thrilling scene, which was so well

acted out by men, women, and children, and (apparently) by their

dogs, I should scarcely have had the nerve to have been a close observer

but for the announcement by the fur-trader, Mr. Kipp, with

whom I was lodging, that this was the beginning of the "great

ceremony," and that I ought not to lose a moment in witnessing its

commencement, and of making sketches of all that transpired.

With this advice Mr. Kipp had accompanied me to the picket,

where I had a fair view of the reception of this strange visitor from

the West; in appearance a very aged man, whose body was naked,

with the exception of a robe made of four white wolves' skins. His

body and face and hair were entirely covered with white clay, and he

closely resembled, at a little distance, a centenarian white man. In

his left hand he extended, as he walked, a large pipe, which seemed

to be borne as a very sacred thing. The procession moved to the

Medicine Lodge, which this personage seemed to have the only means

of opening. He opened it, and entered it alone, it having been (as

I was assured) superstitiously closed during the past year, and never

used since the last annual ceremony.

The chiefs then retired to the Council-house, leaving this strange

visitor sole tenant of this sacred edifice; soon after which he placed

himself at its door, and called out to the chiefs to furnish him "four

men,—one from the North, one from the South, one from the East,

and one from the West, whose hands and feet were clean and would

not profane the sacred temple while labouring within it during that

day."

These four men were soon produced, and they were employed

and strewing the floor, which was a concrete of gravel and clay,

and ornamenting the sides of it, with willow boughs and aromatic

herbs which they gathered in the prairies, and otherwise preparing

it for the "Ceremonies," to commence on the next morning.

During the remainder of that day, while all the Mandans were

shut up in their wigwams, and not allowed to go out, Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah

(the first or only man) visited alone each wigwam, and,

while crying in front of it, the owner appeared and asked, "Who's

there?" and "What was wanting?" To this Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah

replied by relating the destruction of all the human family

by the Flood, excepting himself, who had been saved in his "Big

Canoe," and now dwelt in the West; that he had come to open

the Medicine Lodge, that the Mandans might make the necessary sacrifices

to the water, and for this purpose it was requisite that he

should receive at the door of every Mandan's wigwam some edged

tool to be given to the water as a sacrifice, as it was with such tools

that the "Big Canoe" was built.

He then demanded and received at the door of every Mandan

wigwam, some edged or pointed tool or instrument made of iron or

steel, which seemed to have been procured and held in readiness for

the occasion; with these he returned to the Medicine Lodge at evening,

where he deposited them, and where they remained during the

four days of the ceremony, and were, as will be seen, on the last day

at sundown, in the presence of the chiefs and all the tribe, to be

thrown into deep water from the top of the rocks, and thus made a

sacrifice to the water.

Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah rested alone in the Medicine Lodge during

that night, and at sunrise the next morning, in front of the lodge,

called out for all the young men who were candidates for the

O-kee-pa graduation as warriors, to come forward,—the rest of the

villagers still enclosed in their wigwams.

In a few minutes about fifty young men, whom I learned were

all of those of the tribe who had arrived at maturity during the last

year, appeared in a beautiful group, their graceful limbs entirely

denuded, but without exception covered with clay of different colours

from head to foot,—some white, some red, some yellow, and others

blue and green, each one carrying his shield of bull's hide on his left

arm, and his bow in his left hand, and his medicine bag in the right.

In this plight they followed Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah into the Medicine

Lodge in "Indian file," and taking their positions around the

sides of the lodge, each one hung his bow and quiver, shield and

medicine-bag over him as he reclined upon the floor of the wigwam.

Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah then called into the Medicine Lodge the

principal medicine man of the tribe, whom he appointed O-kee-pa-ka-see-ka

(Keeper or Conductor of the Ceremonies), by passing into

his hand the large pipe which he had so carefully brought with

him, "which had been saved in the big canoe with him," and on

which it will appear the whole of these mysteries hung.

Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah then took leave of him by shaking hands

with him, and left the Medicine Lodge, saying that he would return to

the West, where he lived, and be back again in just a year to reopen

the Medicine Lodge. He then passed through the village, shaking

hands with the chiefs, and in a few moments was seen disappearing

over the hills from whence he came the day previous.

No more was seen of this extraordinary personage during the

ceremonies, but more will be learned of him before this description

is finished.[1]

Here is the proper place to relate the manner in which I gained

admission into this sacred temple, and to give the credit that was due,

to the man who kindly gave me permission to witness what was probably

never seen before by a white man, the secret and sacred transactions

of the interior of the Mandan Medicine Lodge, so sacred that

a double door, with an intervening passage and an armed sentinel at

each end, positively denying all access except by permission of the

Conductor of the Ceremonies, and strictly guarding it against the

approach or gaze of women, who, I was told, had never been allowed

to catch the slightest glance of its interior.

This interior had also been too sacred a place for the admission of

Mr. Kipp, the fur-trader, who had lived in the village eight or ten

years; but luckily for me, I had completed a portrait the day before,

of the renowned doctor or "mystery man," to whom the superintendence

of the ceremonies had just been committed, and whose

vanity had been so much excited by the painting that he had

mounted on to a wigwam with it, holding it up by the corners and

haranguing the villagers, claiming that "he must be the greatest

man among the Mandans, because I had painted his portrait before I

had painted the great chief; and that I was the greatest `medicine'

of the whites, and a great chief, because I could make so perfect a

duplicate of him that it set all the women and children laughing!"

This man, then, in charge of the Medicine Lodge, seeing me with

one of my men and Mr. Kipp, the fur trader, standing in front of

the door, came out, and passing his arm through mine, politely led

me into the lodge, and allowing my hired man and Mr. Kipp, with

one of the clerks of his establishment, to follow. We took our seats,

and were allowed to resume them on the three following days, occupying

them most of the time from sunrise to sundown; and therefore

the following description of those scenes, and the paintings

which I then made of them, and to all of which Mr. Kipp and the

other two men attached their certificates, which are here given.

"We hereby certify that we witnessed, with Mr. Catlin, in the Mandan

village, the ceremonies represented in the four paintings to which this certificate

refers, and that he has therein represented those scenes as we saw

them enacted, without addition or exaggeration.

The Conductor or Master of the Ceremonies then took his position,

reclining on the ground near the fire, in the centre of the

lodge, with the medicine-pipe in his hand, and commenced crying,

and continued to cry to the Great Spirit, while he guarded the young

candidates who were reclining around the sides of the lodge, and for

four days and four nights were not allowed to eat, drink, or to sleep.

(This interior, which they called "Mee-ne-ro-ka-Há-sha,"—the waters

settle down,—see in Plate III.)

By such denial great lassitude, and even emaciation, was produced,

preparing the young men for the tortures which they afterwards

went through.

The Medicine Lodge, in which they were thus resting during the

four days, and which I have said was seventy-five feet in diameter,

presented the most strange and picturesque appearance. Its sides

were curiously decorated with willow-boughs and aromatic herbs,

and its floor (covered also with willow-boughs) with a curious

arrangement of buffalo and human skulls.

There were also four articles of veneration and importance lying

on the ground, which were sacks, containing each some three or

four gallons of water. These seemed to be objects of great superstitious

regard, and had been made with much labour and ingenuity,

being constructed of the skins of the buffalo's neck, and sewed

together in the forms of large tortoises lying on their backs, each

having a sort of tail made of raven's quills, and a stick like a drumstick

the ceremony, the musicians beat upon the sacks as instruments of

music for their strange dances.

By the sides of these sacks, which they called Eeh-tee-ka (drums),

there were two other articles of equal importance, which they called

Eeh-na-de (rattles), made of dried undressed skins, shaped into the

form of gourd-shells, which they also used, as will be seen, as another

part of the music for their dances.

The sacks of water had the appearance of great antiquity, and

the Mandans pretended that the water had been contained in them

ever since the Deluge. At what time it had been originally put

in, or when replenished, I consequently could not learn. I made

several efforts to purchase one of these tortoise drums, so elaborately

and curiously were they embroidered and ornamented, offering them

goods at the Fur Company's trading-house to the value of one hundred

dollars, but they said they were medicine (mystery) things, and

therefore could not be sold at any price.

Such was the appearance of the interior of the Medicine Lodge

during the three first (and part of the fourth) days. During the

three first days, while things remained thus inside of the Medicine

Lodge, there were many curious and grotesque amusements and

ceremonies transpiring outside and around the "Big Canoe."

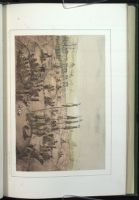

The principal of these, which they called Bel-lohk-na-pick (the

bull dance), to the strict observance of which they attributed the

coming of buffaloes to supply them with food, was one of an exceedingly

grotesque and amusing character, and was danced four times

on the first day, eight times on the second day, twelve times on the

third day, and sixteen times on the fourth day, and always around

the "Big Canoe," of which I have already spoken. (See the "Bull

Dance," Plate IV.)

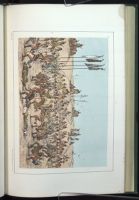

The chief actors in these strange scenes were eight men, with the

entire skins of buffaloes thrown over them, enabling them closely

of the dancers were kept in a horizontal position, the horns and

tails of the animals remaining on the skins, and the skins of the

animals' heads served as masks, through the eyes of which the

dancers were looking.

The eight men were all naked and painted exactly alike, and in

the most extraordinary manner; their bodies, limbs, and faces being

everywhere covered with black, red, or white paint. Each joint was

marked with two white rings, one within the other, even to the

joints in the under jaw, the fingers and the toes; and the abdomens

were painted to represent the face of an infant, the navel representing

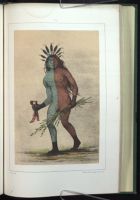

its mouth. (See "A Buffalo Bull," Plate V.[2]

)

Each one of these characters also had a lock of buffalo's hair tied

around the ankles, in his right hand a rattle (she-shée-quoin), and

a slender staff six feet in length in the other; and carried on his

back, above the buffalo skin, a bundle of willow-boughs, of the ordinary

size of a bundle of wheat. (See "A Buffalo Bull" dancing,

Plate VI.)

These eight men representing eight buffalo bulls, being divided

into four pairs, took their positions on the four sides of the Ark,

or "Big Canoe" (as seen in the general view, Plate IV.), representing

thereby the four cardinal points; and between each couple

of these, with his back turned to the "Big Canoe," was another

figure engaged in the same dance, keeping step with the eight

buffalo bulls, with a staff in one hand and a rattle in the other: and

being four in number, answered again to the four cardinal points.

The bodies of these four men were also entirely naked, with the

exception of beautiful kilts of eagles' quills and ermine, and headdresses

made of the same materials.

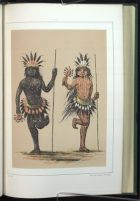

Two of these figures were painted jet black with charcoal and

grease, whom they called the night, and the numerous white spots

dotted over their bodies and limbs they called stars. (See one of

these, Plate VII.)

The other two, who were painted from head to foot as red as

vermilion could make them, with white stripes up and down over

their bodies and limbs, were called the morning rays (symbols of day).

(See one of them, Plate VII.)

These twelve were the only figures actually engaged in the Bull

dance, which was each time repeated in the same manner without

any apparent variation. There were, however, a great number of

characters, many of them representing various animals of the country,

engaged in giving the whole effect to this strange scene, and all

of which are worthy of a few remarks.

The bull dance was conducted by the old master of ceremonies

(O-kee-pa Ka-see-ka) carrying his medicine pipe; his body entirely

naked, and covered, as well as his hair, with yellow clay.

For each time that the bull dance was repeated, this man came

out of the Medicine Lodge with the medicine pipe in his hands, bringing

with him four old men carrying the tortoise drums, their bodies

painted red, and head-dresses of eagles' quills, and with them another

old man with the two she-shée-quoins (rattles). These took their

seats by the side of the "Big Canoe," and commenced drumming

and rattling and singing, whilst the conductor of the ceremonies,

with his medicine pipe in his hands, was leaning against the "Big

Canoe," and crying in his full voice to the Great Spirit, as seen in

the general view, Plate IV. Squatted on the ground, on the opposite

side of the "Big Canoe," were two men with skins of grizzly bears

thrown over them, using the skins as masks covering their faces.

Their bodies were naked, and painted with yellow clay.

These characters, whom they called grizzly bears, were continually

growling and threatening to devour everything before them, and

keep them quiet, the women were continually bringing and placing

before them dishes of meat, which were as often snatched away and

carried to the prairies by two men called bald eagles, whose bodies

and limbs were painted black, whilst their heads and feet and hands

were whitened with clay. These were again chased upon the

prairies by a numerous group of small boys, whose bodies and limbs

were painted yellow, and their heads white, wearing tails of white

deer's hair, and whom they called antelopes.

Besides these there were two men representing swans, their

bodies naked and painted white, and their noses and feet were

painted black.

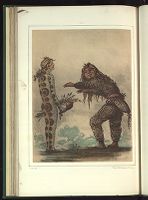

There were two men called rattlesnakes, their bodies naked and

curiously painted, resembling that reptile; each holding a rattle in

one hand and a bunch of wild sage in the other. (See "A Rattlesnake,"

Plate VIII.) There were two beavers, represented by two

men entirely covered with dresses made of buffalo skins, except

their heads, and wearing beavers' tails attached to their belts. (See

"A Beaver," Plate VIII.)

There were two men representing vultures, their bodies naked and

painted brown, their heads and shoulders painted blue, and their

noses red.

Two men represented wolves, their bodies naked, wearing wolf-skins.

These pursued the antelopes, and whenever they overtook

one of them on the prairie one or both of the grizzly bears came up

and pretended to devour it, in revenge for the antelopes having

devoured the meat given to the grizzly bears by the women.

All these characters closely imitated the habits of the animals

they represented, and they all had some peculiar and appropriate

songs, which they constantly chanted and sang during the dances,

without even themselves (probably) knowing the meaning of them,

they being strictly medicine songs, which are kept profound secrets

initiated into their medicines (mysteries) at an early age, and at an

exorbitant price; and I therefore failed to get a translation of them.

At the close of each of these bull dances, these representatives of

animals and birds all set up the howl and growl peculiar to their

species, in a deafening chorus; some dancing, some jumping, and

others (apparently) flying; the beavers clapping with their tails,

the rattlesnakes shaking their rattles, the bears striking with their

paws, the wolves howling, and the buffaloes rolling in the sand or

rearing upon their hind feet; and dancing off together to an adjoining

lodge, where they remained in a curious and picturesque group

until the master of ceremonies came again out of the Medicine Lodge,

and leaning as before against the "Big Canoe," cried out for all the

dancers, musicians, and the group of animals and birds to gather

again around him.

This lodge, which was also strictly a Medicine Lodge during the

occasion, and used for painting and arranging all the characters, and

not allowed to be entered during the four days, except by the persons

taking part in the ceremonies, was shown to me by the conductor of

the ceremonies, who sent a medicine man with me to its interior

whilst the scene of painting and ornamenting their bodies for the

bull dance was taking place; and none but the most vivid imagination

could ever conceive anything so peculiar, so wild, and so curious in

effect as this strange spectacle then presented to my view.

No man painted himself, but, standing or lying naked, submitted

like a statue to the operations of other hands, who were appointed

for the purpose. Each painter seemed to have his special department

or peculiar figure, and each appeared to be working with great care

and with ambition for the applause of the public when he turned out

his figure.

It may be thought easy to imagine such a group of naked figures,

and the effect that the rude painting on their bodies would have; but

appreciate the singular beauty of these graceful figures thus decorated

with various colours, reclining in groups, or set in rapid motion; it

was one of those few scenes that must be witnessed to be fully

appreciated.

The first ordeal they all went through in this sanctuary was that

of Tah-ke-way ka-ra-ka (the hiding man), the name given to an

aged man, who was supplied with small thongs of deer's sinew, for

the purpose of obscuring the glans secret, which was uniformly done

by this operator, with all the above-named figures, by drawing the

prepuce over in front of the glans, and trying it secure with the sinew,

and then covering the private parts with clay, which he took from a

wooden bowl, and, with his hand, plastered unsparingly over.

Of men performing their respective parts in the bull dance,

representing the various animals, birds, and reptiles of the country,

there were about forty, and forty boys representing antelopes,—

making a group in all of eighty figures, entirely naked, and painted

from head to foot in the most fantastic shapes, and of all colours, as

has been described; and the fifty young men resting in the Medicine

Lodge, and waiting for the infliction of their tortures, were also

naked and entirely covered with clay of various colours (as has been

described), some red, some yellow, and others blue and green; so

that of (probably) one hundred and thirty persons engaged in these

picturesque scenes, not one single inch of the natural colour of their

bodies, their limbs, or their hair could be seen!

During each and every one of these bull dances, the four old men

who were beating on the sacks of water, were chanting forth their

supplications to the Great Spirit for the continuation of his favours,

in sending them buffaloes to supply them with food for the ensuing

year. They were also exciting the courage and fortitude of the

young men inside of the Medicine Lodge, who were listening to their

prayers, by telling them that "the Great Spirit had opened his ears

peace and happiness for them when they got through; that the

women and children could hold the mouths and paws of the grizzly

bears; that they had invoked from day to day the Evil Spirit; that

they were still challenging him to come, and yet he had not dared to

make his appearance."

But, in the midst of the last dance on the fourth day, a sudden

alarm throughout the group announced the arrival of a strange

character from the West. Women were crying, dogs were howling;

and all eyes were turned to the prairie, where, a mile or so in distance,

was seen an individual man making his approach towards the

village; his colour was black, and he was darting about in different

directions, and in a zigzag course approached and entered the village,

amidst the greatest (apparent) imaginable fear and consternation of

the women and children.

This strange and frightful character, whom they called O-ke-hée-de

(the owl or Evil Spirit), darted through the crowd where the

buffalo dance was proceeding (as seen in Plate IV.), alarming all

he came in contact with. His body was painted jet black with

pulverized charcoal and grease, with rings of white clay over his

limbs and body. Indentations of white, like huge teeth, surrounded

his mouth, and white rings surrounded his eyes. In his two hands

he carried a sort of wand—a slender rod of eight feet in length, with

a red ball at the end of it, which he slid about upon the ground as

he ran. (See "O-ke-hée-de," Plate IX.)

On entering the crowd where the buffalo dance was going on, he

directed his steps towards the groups of women, who retreated in the

greatest alarm, tumbling over each other and screaming for help as

he advanced upon them. At this moment of increased alarm the

screams of the women had brought by his side O-kee-pa-ká-see-ka

(the conductor of the ceremonies) with his medicine pipe, for their

protection. This man had left the "Big Canoe," against which he

pipe before this hideous monster, and, looking him full in the eyes,

held him motionless under its charm, until the women and children

had withdrawn from his reach.

The awkwardness of the position of this blackened demon, and

the laughable appearance of the two, frowning each other in the face,

while the women and children and the whole crowd were laughing

at them, were amusing beyond the power of description.

After a round of hisses and groans from the crowd, and the

women had retired to a safe distance, the medicine pipe was gradually

withdrawn, and this vulgar monster, whose wand was slowly lowering

to the ground, gained power of locomotion again.

The conductor of the ceremonies returned to the "Big Canoe,"

and resumed his former position and crying, as the buffalo dance

was still proceeding, without interruption.

The Evil Spirit in the meantime had wandered to another part of

the village, where the screams of the women were again heard, and

the conductor of the ceremonies again ran with the medicine pipe in

his hands to their rescue, and arriving just in time, and holding this

monster in check as before, enabled them again to escape.

In several attempts of this kind the Evil Spirit was thus defeated,

after which he came wandering back amongst the dancers, apparently

much fatigued and disappointed; and the women gradually advancing

and gathering around him, evidently less apprehensive of danger

than a few moments before.

In this distressing dilemma he was approached by an old matron,

who came up slily behind him with both hands full of yellow dirt,

which (by reaching around him) she suddenly dashed in his face,

covering him from head to foot and changing his colour, as the dirt

adhered to the undried bears'-grease on his skin. As he turned

around he received another handful, and another, from different

quarters; and at length another snatched his wand from his hands,

snapping them into small bits, threw them into his face. His power

was thus gone, and his colour changed: he began then to cry, and,

bolting through the crowd, he made his way to the prairies, where

he fell into the hands of a fresh swarm of women and girls (no doubt

assembled there for the purpose) outside of the picket, who hailed

him with screams and hisses and terms of reproach, whilst they

were escorting him for a considerable distance over the prairie, and

beating him with sticks and dirt.

He was at length seen escaping from this group of women, who

were returning to the village, whilst he was disappearing over the

plains from whence he had made his first appearance.

The crowd of women entered the village, and the area where the

ceremony was transpiring, in triumph, and the fortunate one who

had deprived him of his power was escorted by two matrons on each

side. She was then lifted by her four female attendants on to the

front of the Medicine Lodge, directly over its door, where she stood

and harangued the multitude for some time; claiming that "she

held the power of creation, and also the power of life and death over

them; that she was the father of all the buffaloes, and that she could

make them come or stay away, as she pleased."

She then ordered the bull dance to be stopped—the four musicians

to carry the four tortoise-drums into the Medicine Lodge. The assistant

dancers and all the other characters taking p

into the dressing and pan-lodge. The and

on the floor of the Medicine Lodge (as seen in Plate III.) she ordered

to be hung on the four posts (as seen in Plate X.). She

the chiefs to enter the Medicine Lodge, and (being seated) to witness

the voluntary tortures of the young men, now to commence. She

ordered the conductor of the ceremonies to sit by the fire and smoke

the medicine pipe, and the operators to go in with their knife and

splints, and to commence the tortures.

Catlin del

Photo-th Simonau & Toovey.

Catlin del

Photo-th Simonau &

Catlin del

Photo-th Simonau & Toovey.

Catlin del

Photo-th Simonau & Toovey

Catlin del

Photo-th Simonau & Toovey

Catlin del

Photo-th Simonau & Toovey.

Catlin del

Photo-th Simonau & Toovey.

Catlin del

Photo-th Simonau & Toovey.

Catlin del

Photo-lith Simonau & Toovey

Catlin del

Photo-th Simonau & Toovey

Catlin del

Photo-th Simonau & Toovey

She then called out for and demanded the handsomest woman's

dress in the Mandan village, which was due to her who had disarmed

O-ke-hee-de and had the power of making all the buffaloes which the

Mandans would require during the coming year. Her demand for

this beautiful dress was peremptory, and she must have it to lead the

dance in the Feast of the Buffaloes, to be given that night.

The beautiful dress was then presented to her by the conductor

of the ceremonies, who said to her, "Young woman, you have gained

great fame this day; and the honour of leading the dance in the

Feast of the Buffaloes, to be given this night, belongs to you."

Thus ended the bull dance (bel-lohk-ná-pick) and other amusements

at midday on the fourth day of the O-kée-pa, preparatory to

the scenes of torture to take place in the Medicine Lodge; and the

pleasing moral from these strange (and in some respects disgusting)

modes, at once suggests itself, that in the midst of their religious

ceremony the Evil Spirit had made his entrée for the purpose of

doing mischief, and, having been defeated in all his designs by the

magic power of the medicine pipe, on which all those ceremonies

hung, he had been disarmed and driven out of the village in disgrace

by the very part of the community he came to impose upon.

The bull dance and other grotesque scenes being finished outside

of the Medicine Lodge, the torturing scene (or pohk-hong as they called

it) commenced within, in the following manner. (See Plate X.)

The young men reclining around the sides of the Medicine Lodge

(before shown in Plate III.), who had now reached the middle

of the fourth day without eating, drinking, or sleeping, and consequently

weakened and emaciated, commenced to submit to the

operation of the knife and other instruments of torture.

Two men, who were to inflict the tortures, had taken their positions

near the middle of the lodge; one, with a large knife with a

sharp point and two edges, which were hacked with another knife

in order to produce as much pain as possible, was ready to make the

splints of the size of a man's finger, and sharpened at both ends, to

be passed through the wounds as soon as the knife was withdrawn.

The bodies of these two men, who were probably medicine men,

were painted red, with their hands and feet black; and the one who

made the incisions with the knife wore a mask, that the young men

should never know who gave them their wounds; and on their

bodies and limbs they had conspicuously marked with paint the scars

which they bore, as evidence that they had passed through the same

ordeal.

To these two men one of the emaciated candidates at a time

crawled up, and submitted to the knife (as seen in Plate X.),

which was passed under and through the integuments and flesh taken

up between the thumb and forefinger of the operator, on each arm,

above and below the elbow, over the brachialis externus and the

extensor radialis, and on each leg above and below the knee, over

the vastus externus and the peroneus; and also on each breast and each

shoulder.

During this painful operation, most of these young men, as they

took their position to be operated upon, observing me taking notes,

beckoned me to look them in the face, and sat, without the apparent

change of a muscle, smiling at me whilst the knife was passing

through their flesh, the ripping sound of which, and the trickling of

blood over their clay-covered bodies and limbs, filled my eyes with

irresistible tears.

When these incisions were all made, and the splints passed

through, a cord of raw hide was lowered down through the top of

the wigwam, and fastened to the splints on the breasts or shoulders,

by which the young man was to be raised up and suspended, by men

placed on the top of the lodge for the purpose.

These cords having been attached to the splints on the breast or

the shoulders, each one had his shield hung to some one of the splints:

was attached to the splint on each lower leg and each lower arm, that

its weight might prevent him from struggling; when, at a signal,

by striking the cord, the men on top of the lodge commenced to draw

him up. He was thus raised some three or four feet above the ground,

until the buffalo heads and other articles attached to the wounds

swung clear, when another man, his body red and his hands and feet

black, stepped up, and, with a small pole, began to turn him around.

The turning was slow at first, and gradually increased until

fainting ensued, when it ceased. In each case these young men

submitted to the knife, to the insertion of the splints, and even to

being hung and lifted up, without a perceptible murmur or a groan;

but when the turning commenced, they began crying in the most

heartrending tones to the Great Spirit, imploring him to enable them

to bear and survive the painful ordeal they were entering on. This

piteous prayer, the sounds of which no imagination can ever reach,

and of which I could get no translation, seemed to be an established

form, ejaculated alike by all, and continued until fainting commenced,

when it gradually ceased.

In each instance they were turned until they fainted and their

cries were ended. Their heads hanging forwards and down, and

their tongues distended, and becoming entirely motionless and silent,

they had, in each instance, the appearance of a corpse. (See Plate

XI.) In this view, which was sketched whilst the two young men

were hanging before me, one is suspended by the muscles of the

breast, and the other by the muscles of the shoulders, and two of the

young candidates are seen reclining on the ground, and waiting for

their turn.

When brought to this condition, without signs of animation, the

lookers-on pronounced the word dead! dead! when the men who

had turned them struck the cords with their poles, which was the

signal for the men on top of the lodge to lower them to the ground,

minutes.

The excessive pain produced by the turning, which was evinced

by the increased cries as the rapidity of the turning increased, was

no doubt caused by the additional weight of the buffalo skulls upon

the splints, in consequence of their centrifugal direction, caused by

the rapidity with which the bodies were turned, added to the sickening

distress of the rotary motion; and what that double agony

actually was, every adult Mandan knew, and probably no human

being but a Mandan ever felt.

After this ordeal (in which two or three bodies were generally

hanging at the same time), and the bodies were lowered to the

ground as has been described, a man advanced (as is seen in Plate

X.) and withdrew the two splints by which they had been hung

up, they having necessarily been passed under a portion of the

trapezius or pectoral muscle, in order to support the weight of their

bodies; but leaving all the others remaining in the flesh, to be got

rid of in the manner yet to be described.

Each body lowered to the ground appeared like a loathsome and

lifeless corpse. No one was allowed to offer them aid whilst they

lay in this condition. They were here enjoying their inestimable

privilege of voluntarily entrusting their lives to the keeping of the

Great Spirit, and chose to remain there until the Great Spirit gave

them strength to get up and walk away.

In each instance, as soon as they got strength enough partly to

rise, and move their bodies to another part of the lodge, where there

sat a man with a hatchet in his hand and a dried buffalo skull before

him, his body red, his hands and feet black, and wearing a mask,

they held up the little finger of the left hand (as seen in Plate X.)

towards the Great Spirit (offering it as a sacrifice, as they thanked

him audibly, for having listened to their prayers and protected their

lives in what they had just gone through), and laid it on the buffalo

the hatchet, close to the hand.

In several instances I saw them offer immediately after, and give,

the forefinger of the same hand,—leaving only the two middle fingers

and the thumb to hold the bow, the only weapon used in that hand.

Instances had been known, and several such were subsequently shown

to me amongst the chiefs and warriors, where they had given also

the little finger of the right hand, a much greater sacrifice; and

several famous men of the tribe were also shown to me, who proved,

by the corresponding scars on their breasts and limbs, which they

exhibited to me, that they had been several times, at their own

option, through these horrid ordeals.

The young men seemed to take no care or notice of the wounds

thus made, and neither bleeding nor inflammation to any extent

ensued, though arteries were severed,—owing probably to the checked

circulation caused by the reduced state to which their four days and

nights of fasting and other abstinence had brought them.

During the whole time of this cruel part of the ceremonies, the

chiefs and other dignitaries of the tribe were looking on, to decide

who amongst the young men were the hardiest and stoutest-hearted,

who could hang the longest by his torn flesh without fainting, and

who was soonest up after he had fainted,—that they might decide

whom to appoint to lead a war party, or to place at the most important

posts, in time of war.

As soon as six or eight had passed through the ordeal as above

described, they were led out of the Medicine Lodge, with the weights

still hanging to their flesh and dragging on the ground, to undergo

another and (perhaps) still more painful mode of suffering.

This part of the ceremony, which they called Eeh-ke-náh-ka

Na-pick (the last race) (see Plate XII.), took place in presence of

the whole tribe, who were lookers-on. For this a circle was formed

by the buffalo dancers (their masks thrown off) and others who had

quills, and all connected by circular wreaths of willow-boughs held

in their hands, who ran, with all possible speed and piercing yells,

around the "Big Canoe;" and outside of that circle the bleeding

young men thus led out, with all their buffalo skulls and other

weights hanging to the splints, and dragging on the ground, were

placed at equal distances, with two athletic young men assigned to

each, one on each side, their bodies painted one half red and the other

blue, and carrying a bunch of willow-boughs in one hand, (see one

of them, Plate XIII.,) who took them, by leather straps fastened

to the wrists, and ran with them as fast as they could, around the

"Big Canoe;" the buffalo skulls and other weights still dragging on

the ground as they ran, amidst the deafening shouts of the bystanders

and the runners in the inner circle, who raised their voices to the

highest key, to drown the cries of the poor fellows thus suffering by

the violence of their tortures.

The ambition of the young aspirants in this part of the ceremony

was to decide who could run the longest under these circumstances

without fainting, and who could be soonest on his feet again after

having been brought to that extremity. So much were they exhausted,

however, that the greater portion of them fainted and

settled down before they had run half the circle, and were then

violently dragged, even (in some cases) with their faces in the dirt,

until every weight attached to their flesh was left behind.

This must be done to produce honourable scars, which could not

be effected by withdrawing the splints endwise; the flesh must be

broken out, leaving a scar an inch or more in length: and in order to

do this, there were several instances where the buffalo skulls adhered

so long that they were jumped upon by the bystanders as they were

being dragged at full speed, which forced the splints out of the

wounds by breaking the flesh, and the buffalo skulls were left behind.

The tortured youth, when thus freed from all weights, was left

torturers, having dropped their willow-boughs, were seen running

through the crowd towards the prairies, as if to escape the punishment

that would follow the commission of a heinous crime.

In this pitiable condition each sufferer was left, his life again

entrusted to the keeping of the Great Spirit, the sacredness of which

privilege no one had a right to infringe upon by offering a helping

hand. Each one in his turn lay in this condition until "the Great

Spirit gave him strength to rise upon his feet," when he was seen,

covered with marks of trickling blood, staggering through the crowd

and entering his wigwam, where his wounds were probably dressed,

and with food and sleep his strength was restored.

The chiefs and other dignitaries of the tribe were all spectators

here also, deciding who amongst the young men were the strongest,

and could run the longest in the last race without fainting, and whom

to appoint and promote accordingly.

As soon as the six or eight thus treated were off from the

ground, as many more were led out of the Medicine Lodge and passed

through the same ordeal, or took some other more painful mode, at

their own option, to rid themselves of the splints and weights

attached to their limbs, until the whole number of candidates were

disposed of; and on the occasion I am describing, to the whole of

which I was a spectator, I should think that about fifty suffered in

succession, and in the same manner.

The number of wounds inflicted required to be the same on each,

and the number of weights attached to them the same, but in both

stages of the torture the candidates had their choice of being, in the

first, suspended by the breasts or by the shoulders; and in the "last

race" of being dragged as has been described, or to wander about the

prairies from day to day, and still without food, until suppuration of

the wounds took place, and, by the decay of the flesh, the dragging

weights were left behind.

It was natural for me to inquire, as I did, whether any of these

young men ever died in the extreme part of this ceremony, and they

could tell me of but one instance within their recollection, in which

case the young man was left for three days upon the ground (unapproached

by his relatives or by physicians) before they were quite

certain that the Great Spirit did not intend to help him away. They

all seemed to speak of this, however, as an enviable fate rather than

as a misfortune; for "the Great Spirit had so willed it for some

especial purpose, and no doubt for the young man's benefit."

After the Medicine Lodge had thus been cleared of its tortured

inmates, the master or conductor of ceremonies returned to it alone,

and, gathering up the edged tools which I have said were deposited

there, and to be sacrificed to the water on the last day of the ceremony,

he proceeded to the bank of the river, accompanied by all the

tribe, in whose presence, and with much form and ceremony, he

sacrificed them by throwing them into deep water from the rocks,

from which they could never be recovered: and then announced

that the Great Spirit must be thanked by all—and that the O-kee-pa

(religious ceremony of the Mandans) was finished.

The sequel to this strange affair, and which has been briefly

alluded to, and is yet to be described, was the

"Feast of the Buffaloes."

At the defeat of O-ke-hée-de (the Evil Spirit) it will be remembered

that the young woman who returned from the prairie bearing the

singular prize, and who ascended the front of the Medicine Lodge and

put an end to the bull dance, claimed the privilege of a beautiful

dress, in which she was to lead the dance in the feast of the buffaloes

on that night.

The O-kee-pa having been ended, and night having approached,

several old men with rattles in their hands, which they were violently

character of criers, announcing that "the whole government of the

Mandans was then in the hands of one woman—she who had disarmed

the Evil Spirit, and to whom they were to look during the

coming year for buffaloes to supply them with food, and keep them

alive; that all must repair to their wigwams and not show themselves

outside; that the chiefs on that night were old women; that

they had nothing to say; that no one was allowed to be out of

their wigwams excepting the favoured ones whom Rah-ta-co-puk-chee

(the governing woman) had invited to be at the feast of the buffaloes

around the `Big Canoe,' and which was about to commence."

This select party, which assembled and was seated on the ground

in a circle, and facing the "Big Canoe," consisted (first) of the

eight men who had danced the bull dance, with the paint washed off.

To them strictly the feast was given, and therefore was the feast of

the buffaloes (and not to be confounded with the buffalo feast, another

annual ceremony, given in the fall of the year, somewhat of a similar

character, but held for a different purpose).

Besides the eight buffaloes were the old medicine man, conductor

of the ceremonies, the four old men who had beaten on the tortoise-drums,

and the one who had shaken the rattles, as musicians, and

several of the aged chiefs of the tribe; and, added to these, this new-made,

but temporary governess of the tribe, had invited some eight

or ten of the young married women of the village, like herself, to

pay the extraordinary respect that was due, by the custom of their

country, to the makers of buffaloes and to reverenced old age on this

extraordinary occasion.

The commencement of the ceremonies which fell under this

woman's peculiar management was the feast of the buffaloes (as all the

men invited to it were called buffaloes), which was handed around in

wooden bowls by herself and attendants. After this was done, which

lasted but a few minutes (appearing but a minor part of the affair),

during which a lascivious dance was performed by herself and female

companions.

This dance finished, she advanced to her first selected paramour,

and, giving some signals which seemed to be understood, passed her

hand gently under his arm, and, raising him up, led him through the

village and into the prairie, where, as all the villagers and their dogs

were shut up in their wigwams, they were free from observation or

molestation.[3]

From this excursion they returned separately, and the man took

his seat again if he chose to be a candidate for further civilities, or

returned to his wigwam. The other women were singing and going

through the whirl of the dance in the meantime, and each one inviting

her chosen paramour, when she was disposed, in the same

manner.

Those of the women who returned from these excursions joined

again in the continuous dance, and extended as many and as varied

invitations in this way as they desired; and some of them, I learned,

as well as of the men, had taken several of such promenades in the

course of the evening, which may be accounted for by the relieving

fact that though it would have been a most prejudicial want of

gallantry on the part of the man to have refused to go, yet the

trifling present of a string of beads or an awl saved him from any

odium which might otherwise have been cast upon him.

This extraordinary scene gradually closed by the men returning

from the prairie to their homes, the last of them on the ground

pacifying any unsatisfied feelings there might have been, by bestowing

the pipe of friendship with their husbands the next day, which they

were bound to offer, and the others, by the custom of the country,

were bound to accept.

It may be met as matter of surprise, that a religious ceremony

should be followed by a scene like the one just described, but before

we entirely condemn these ignorant and superstitious people, let us

inquire whether it is not, more or less, an inherent propensity in

human nature (and even practised in some enlightened and Christian

communities) to end extreme sorrow, extreme penitence, and even

mourning for kindred the most loved, in debauch?

What has thus far been related has been simple and easy, as it

has been but the description of what I saw and what I heard; but

what may be expected of me—rational and conclusive deductions from

the above premises—I approach with timidity; rather wishing to

submit the materials for the conclusions of others abler than myself

to explain them, and for whose assistance I will still continue a

few suggestions.

That the Mandans should have had a tradition of a "Deluge"

is by no means singular, when in every tribe I have visited I have

found that they regard some high mountain in their vicinity, on

which, they say, their ancestor or ancestors were saved, and also relate

other vague stories of the destruction of everything else living

on the earth, by the waters.

But that these people should hold an annual celebration of that

event, and that the season of the year for that celebration was decided

by such circumstances as the "willow-bough" and its "full-grown

leaves," and the "medicine bird," and the Medicine Lodge opened by

such a man as "Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah," who represented a white

man, and some other circumstances, is surely a very remarkable

thing, and, as I think, deserves some further attention.

This "Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah" (first or only man) was undoubtedly

prairies on the previous evening, and having dressed and painted

himself for the occasion, came into the village at sunrise in the

morning, endeavouring to keep up the semblance of reality; for the

traditions of the Mandans say, that "at an ancient period such a man

did actually come from the West, that his skin was white, that he

was very old, that he appeared in all respects as has been represented;

and, as has also been stated, that he related the manner of

the destruction of every human being on the earth's surface by

the waters, excepting himself, who was saved in his "Big Canoe" by

landing on a high mountain in the West; that the Mandans and all

other nations were his descendants, and were bound to make annual

sacrifices of edged tools to the water, for with such things his "Big

Canoe" was built; that he instructed the Mandans how to make

their Medicine Lodge, and taught them also the forms of these annual

ceremonies, and told them also that as long as they made these

annual sacrifices and performed these rites to the full letter, they

would be the favoured people of the Great Spirit, and would always

have enough to eat and drink, and that so soon as they departed in

the least degree from these forms their race would begin to decrease

and finally die out.

These superstitious people have, no doubt, been living from time

immemorial under the dread of such an injunction, and in the fear

of departing from it; and as they were living in total ignorance of

its origin, other than this vague tradition, the world will probably

remain in equal ignorance of much of its meaning, as they needs

must be of all Indian traditions, which soon run into fable, thereby

losing much of their system by which they might more easily have

been correctly construed.

It would seem from their tradition of the willow-bough and the

dove, that these people must have had some proximity to some part of

the civilized world, or that missionaries or others had been amongst

Deluge, which is in this and some other respects very different from

the theories which all the other American tribes have distinctly

established of that event.

There are other strong, and I think almost conclusive proofs, in

support of this suggestion, which are to be drawn from the diversity

of colour in their hair and complexions, as well as from their traditions

just related of the "first or only man," whose body was white,

and who came from the West, telling them of the destruction of the

human race by the water; and in addition to the above I will offer

another tradition, related to me by one of the chiefs of the tribe in

the following way:—

"At a very ancient time O-ke-hée-de (the Evil Spirit) came from

the West to the Mandan village in company with Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah

(the first or only man), and they, being fatigued, sat down upon

the ground near a woman who had but one eye and was hoeing corn.

Her daughter, who was very beautiful, came up to her, and the Evil

Spirit desired her to go and bring some water, but wished that

before she started she would come to him and eat some buffalo

meat.

"He then told her to take a piece out of his side, which she did,

and ate it, and it proved to be buffalo's fat. She then went for the

water, which she brought, and met them in the village where they

had walked, and they both drank of it; nothing more was done.

The friends of the girl soon after endeavoured to disgrace her by

telling her that she was with child, which she did not deny. She

declared at the same time her innocence, and boldly defied any man

in the Mandan nation to come forward and accuse her. No one

could accuse her, and she therefore became great `medicine,' and

she soon after went to the little Mandan village, where the child was

born.

"Great search was made for her before she was found, as it was

way be of great importance to the tribe. They were induced to this

belief from the strange manner of its conception and birth, and were

soon confirmed in their belief from the wonderful things which it did

at an early age.

"Amongst the strange things which it did on an occasion when

the Mandans were in danger of starving, this child gave them four

buffalo bulls, which filled the bellies of the whole nation, leaving as

much meat as there was before they began to eat, and saying also

that these four bulls would supply them for ever.

"Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah (the first or only man) was bent on the

destruction of this child, and after making many fruitless searches

for it, found it hidden in a dark place, and put it to death by throwing

it into the river.

"When O-ke-hée-de (the Evil Spirit) heard of the death of this

child, he sought for Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah with intent to kill him. He

traced him a long distance, and at length overtook him at the Heart

River, seventy miles below the Mandan village, with the `big medicine

pipe' in his hands, the charm or mystery of which protected

him from all his enemies. They soon agreed however to become

good friends, and after smoking the medicine pipe they returned

together to the Mandan village.

"The Evil Spirit was now satisfied, and Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah

told the Mandans never to go beyond the mouth of Heart River to

live, for it was the centre of the world, and to live beyond it would

be destruction to them, and he named it Nat-com-pa-sá-ha (the

heart or centre of the world)."

Such was one of the very vague and imperfect traditions of those

curious people, and I leave it to the world to judge of its similitude

to the Scripture account of the Christian advent.

Omitting in this place their numerous other traditions and superstitions,

I will barely refer to a few singular deductions I have made

the consideration of gentlemen abler than myself to decide upon their

importance.

The Mandans believed that the earth rests on the backs of four

tortoises. They say that "each tortoise rained ten days, making

forty days in all, and the waters covered the earth."

Whenever a Mandan doctor (medicine man) lighted his pipe, he

invariably presented the stem of it to the north, the south, the