| | ||

In his own time, James Parker was probably as well known an engraver as his old friend and partner William Blake.[3] From the time when the two men were fellow-apprentices under James Basire, their careers were significantly parallel until Parker's early death in 1805. They went on a sailing expedition with Thomas Stothard about 1780 and were arrested as spies; they were married within a few days of one another in 1782; they lived in the same house at 27 Broad Street and shared a print-selling business in 1784 — 85; they made engravings for some of the same works;[4] and in the last year of Parker's life Blake was still consulting him about professional matters. Theirs was clearly a life-long and close professional friendship.

James Parker's career probably conforms a good deal more closely to what Blake's parents hoped for him when they apprenticed him in 1772 than Blake's did. Parker was a quiet, orderly, dependable man,[5] whose engravings

An outline of the career of James Parker may help to indicate what William Blake might have become had he been a mere journeyman rather than a genius.

James Parker was born in 1750 and was thus seven years older than William Blake. The earliest record of him is when on 3 August 1773,

Note that Parker was apprenticed not as an adolescent but as a young man of about twenty-three. The difference in age between sixteen (Blake's age in 1773) and twenty-three is, of course, immense; when (presumably) Parker and Blake first met in 1773, Blake was in the throes of adolescence, writing poetry and envious of his elders, while Parker was a young man. On the other hand, Blake was an artistic genius and had already had a year of training as an engraver when Parker began his apprenticeship. Each may have had something to learn from the other.

When William Blake completed his apprenticeship in 1779, he enrolled at the Royal Academy to study further as an artist, but Parker did not.

It was probably about 1780, when Parker was free of his apprenticeship, that he went with Blake and the rising young artist Thomas Stothard on a sketching expedition sailing up the Medway. Stothard made a sketch of their camp by the riverside, with the sail stretched over the boat for a tent, and with a print of it is a note:

According to his Marriage Allegation of 17 August 1782, James Parker (aged 25 and up [i.e., 32]), Stationer of the Parish of St Dunstan in the West, was to marry Ann Serjeantson of Long Preston in the County of York (aged 21 and up) at Long Preston.[11] One wonders how he had met a young woman from as far away as Yorkshire. Can there be a connection with Blake's friend John Flaxman, whose family came from Yorkshire?

On 13 August 1782 "William Blake a Batchelor and Catharine Butcher [or Boucher] a Spinster" took out a license so that they "may solemnize Marriage together", and on 18 August they were married in the church of St Mary, Battersea, just south of London.

Ann Serjeantson Parker became of importance to Blake and his wife, for they all four lived together for more than a year — and perhaps their marriages so close together were a deliberate prelude to this household-sharing.

In 1784 the Blakes and the Parkers set up a print-shop together at 27 Broad Street, Golden Square, Westminster, next door to where Blake had been born and where he was brought up until he went to live with Basire's

Blake's father died in July 1784, and Blake may have inherited enough money to pay for his share of the print-shop partnership with James Parker. He probably acquired then the printing-press with which he was still printing in 1800 and indeed 1827, while Parker may have provided prints for their stock-in-trade. At this time Blake was attending the literary salons of Mrs Harriet Mathew, a minor blue-stocking, and her husband the Reverend Anthony Stephen Mathew had joined John Flaxman in paying for the printing of the little collection called Poetical Sketches by W. B. (1783), A. S. Mathew writing the apologetic preface to it. A year or so later, Blake "continued to benefit from Mrs. Mathew's liberality, and was enabled to continue in partnership, as a Printseller, with his fellow-pupil, Parker, in a shop, No. 27, next door to his father's, in Broad-street".[12]

According to records for payments of the Paving Rates for Golden Square Ward, Westminster, in 1784, "Parker & Blake" replaced William Neville in the last house [No. 27] in Broad Street North before it meets Marshall Street East, next door to James Blake's haberdashery shop at 28 Broad Street, and, on the basis of a rent of £16, they paid a Rate of 16s. 8d.;[13] in 1785 "Jas Parker & Wm Blake [on a rent of £] 18 [paid Poor Rates of £]2..2.. — ",[14] but in fact Blake had moved out in the last quarter of the year.[15]

We do not know how the business was run, or indeed much of what they sold, but it seems likely that Parker and Blake made and printed engravings, while their wives ran the shop itself. At any rate, according to an early biography of Blake, "His wife attended to the business, and Blake continued to engrave, and took Robert, his favourite brother, for a pupil. This speculation did not succeed — his brother too sickened and died; he had a dispute with Parker — the shop was relinquished [by Blake]".[16]

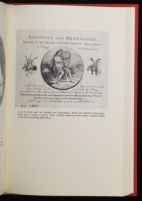

The only prints known to have been published by the firm of Parker & Blake were Blake's oval engravings after their friend Stothard of "Zephyrus

The print-firm of Parker & Blake apparently lasted only a little more than a year at 27 Broad Street, from early 1784 through late 1785. We do not know the cause of the dissolution of the partnership, but the "dispute", if there was one, apparently did not disrupt the long friendship of Parker and Blake. As both men were keen print-collectors, there may have been some difficulty as to which prints were for sale and which were parts of their private collections.

When the firm was dissolved, Blake probably took with him the printing-press, leaving Parker in the shop-premises at 27 Broad Street and perhaps with the stock of prints they had accumulated.

Parker continued paying the Paving Rates at 27 Broad Street in 1787 — 1794,[18] and he probably continued to sell prints there as well. While he was living there, in 1788, "James Parker N° 27 Broad Street Engraver" voted for Townsend (not Hood),[19] and in 1790 he voted for Fox (not Hood or Tooke) and wasted one of his votes.[20] Note that William Blake did not vote in any election when he was qualified to do so by having paid the rates, though his father and brother did.

During the 1790s, both Blake and Parker were comparatively prosperous; about 1795 Blake received the largest commission he was ever to be given, for a hundred and fifty quarto-size engravings in illustration of Young's Night Thoughts (Part One with 43 plates was published in 1797), and Parker was prosperous enough to think of taking an apprentice. On 27 August 1795 John Flaxman wrote to William Hayley saying that Hayley's friend Weller, a carver (like Flaxman's father), wished to apprentice his son to an engraver. "M:r Sharpe is not inclined to take a pupil", but Flaxman's old friend Parker is; "he is one of those Steady, persevering men, who is constantly advancing in the best pursuits of his art, he is besides, religious, mild & conscientious". He would ask £210 for five years.[21] Notice the size of the premium Parker is asking: exactly four times what he and Blake had paid — and for five years rather than seven. He must indeed have been in a prosperous way if he felt he

During these years, Parker worked on some of the most ambitious illustrated books of that or any other time in England: For Robert Bowyer's magnificent folio edition of Hume's History of England (1793 — 1806) he made thirteen plates from 1795 through 1805, including particularly fine ones of "Balliol Surrendering his Crown to Edward I" after Opie (1799 — see Plate 3) and "Charles II. and Sir William Temple" after Stothard (1805); and for the most splendid of them all, John Boydell's Dramatic Works of Shakspeare (1791 — 1802) he engraved eleven folio plates,[22] including an admirable one after Fuseli for Midsummer-Night's Dream (1799) and, even more impressive, an atlas folio plate of Lady Macbeth with the letter after Westall (1800). However, he engraved no plate for Thomas Macklin's equally magnificent The Old [and New] Testament, Embellished with Engravings, from Pictures and Designs by the Most Eminent English Artists (1791 — 1800), though he did make other engravings for Macklin — and was handsomely paid for them: "Fainasollis Borbar & Fingal" (for which he was paid £80 — see Plate 4) and "The Fall of Agandecca" (£180) after J. Barralet and "Cymbeline" (£80) and "The Merry Wives of Windsor" (£70) after S. Harding;[23] they are listed in Macklin's Poetic Description of Choice and Valuable Prints (1794), and the copper-plates were offered in Macklin's posthumous auction 31 March — 4 April 1808 (Peter Coxe).

During these years William Blake's professional career was changing in direction. He had been commissioned about 1795 by Richard Edwards to make 537 large watercolours for Young's Night Thoughts, 150 of which he was to engrave himself, and in 1799 by Thomas Butts to make fifty watercolour illustrations of the Bible. (So far as we know, James Parker made no original designs, though of course he had to copy designs by others in reduced size in order to engrave them.) Further, in 1800 — 1803, Blake largely withdrew from the London engraving market to live as the protegé of William Hayley in the little sea-side village of Felpham in Sussex, making designs and engravings for Hayley's popular poetry and biographies. When he returned to London, he found that the booksellers ignored him. On 7 October 1803 he wrote to Hayley: "Art in London flourishes. Every Engraver turns away work that he cannot execute from his superabundant Employment, yet no one brings work to me. . . . Yet I laugh & sing for if on Earth neglected I am in heaven a Prince among Princes & even on Earth beloved by the Good as a Good Man . . .". And two years later, on 11 December 1805, he wrote again to Hayley: "I was alive & in health & with the same Talents I now have all the

Because they did not say 'O what a Beau ye are'[?] (p. 937)

During these difficult years for Blake, he clearly remained on close terms with Parker, for one of the very small number of the complete collection of four Designs to a Series of Ballads (June — August 1802) by William Hayley engraved and published by Blake has on the original blue paper covers the name in old brown ink of "J. Parker".[25]

About 1801 the engravers who were working on the plates after Robert Smirke's designs for The Arabian Nights (1802), including Heath, Fittler, Anker Smith, Neagle, Parker, Warren, Armstrong, and Raimbach, began to meet monthly at one anothers' houses, and from these meetings grew the Society of Engravers.[26] Clearly Parker was a member of the group, and a "SET OF Engraver's PROOFS [was] PRESENTED TO MR. PARKER by his compeers in this beautiful work".[27] Indeed, he became one of the twenty-four Governors of the Society of Engravers[28] and was influential in the conduct of the profession.

During the brief Peace of Amiens of 1802 — 1803, the amateur illustrated-book publisher F. J. Du Roveray proposed that he should employ French engravers for his next book to foster a rivalry between French and English engravers. The implication that their work needed such a stimulus so incensed the English engravers that they refused for a time to work for Du Roveray — and when England renewed the war with France in 1803 the French engravers were no longer accessible to him. Du Roveray appealed to many English engravers, and particularly to James Parker, to make plates for him. On 24 March 1803 Parker replied to him:

J Parker presents his Compliments to Mr Du Roveray: by his note he finds himself obliged to his friend M.r Stothard, for having 'so often recommended Mr Parker to Mr Du Roveray's notice.' J P wishes not to make any offensive remarks but to be

Spring Place Kentish Town

March. 24.th 1803[29]

This letter exhibits eloquently what his obituary in The Gentleman's Magazine] described as "his equanimity of temper, his suavity of manners, and integrity".

To this Du Roveray drafted a reply:

Sir, I regret to find by your letter of yesterday's date that you are unwilling to exert your abilities in my behalf, until the differences which subsist between some of the associated engravers & myself are made up. I know, for my part, of no diff.es which ought to exist, having given them all the explan.ns they could in reason require: further I do not choose to go; nor will I suffer myself to be dictated to, particularly after the insolent letters I have re'd from Messr A. Smith, Neagle, & Bromley. I could assign Several reasons, for my having omitted the Engravers' names to my Prospectus, such as my having, at the time it went to press, made positive engag.ts with very few, as well as the little dependence which experience has taught me to place upon promises; but I do not think any one has a right to question my motives; nor can any one with propriety take an exception at that which is common to all — so much for the last ground of complaint ag.st me — I am sorry to add that Mr Neagle has been guilty of ingratitude towards me, as well as insolence, as his letters in my possession will prove.

P S. In speaking of the works I have pub.d, you seem to attribute the whole merit of the Plates to the artists in question, forgetting that the Painters are entitled to their full Share of the praise, and that without their successful exertions the finest engraving is of no avail: Such at least is my opinion; and I confess that I think good designs are the first & most essential requisite. After all the finest Plates I have pub.d were not eng.d by the artists in question. They were the work of M.r Heath; who is able & willing Still to employ his talent in embellishing my works. I can say the same of Mr Sharp; whose superior abilities I believe no one will question[.]

- 25 March 1803 I should have no objection to leave the point or points at issue to the decision of Mr Stothard, or any other impartial person[.]

Five weeks later Parker responded:

James Parker is glad to find Mr Du Roveray is ready to disclaim any intention of reflecting on the Engravers engaged in his former works, he hopes on Mr Du Roveray's account his application may be general & that it may remedy as effectually as it would have prevented (if done at the first) those differences which have hindered their mutual exertions. J P can only say he would be glad to see those mutual exertions renewed, or if not & the prevention was not on the side of Mr Du Roveray — he

Spring Place Kentish Town

May 3.d 1803

And a year later he wrote again in a letter postmarked 15 June 1804:

J Parker is exceeding sorry Mr Du Roveray should call while he was not at home as he would have shewn him the Plate of Cecilia[30] but it will not be ready for the present which Mr D will have in a few days[.]

J P assures Mr D that his plate is not hindered by other works being prefer[r]ed, on the contrary engagements entered into previous to his are not compleat, & he has declined offers from several old & respected connexions as he would wish to act uniformly[.] Mr D will recollect that J P did not solicit & that he only engaged for one under particular circumstances, that he might not appear to hinder that peace which Mr D alludes to, & which he has been desirous to effect between Mr D & his old friends & not on his own account —

J P mentioned one Year[31] & he hopes to be so near to his time which shall not be intentionally lengthened — that on comparison Mr D will not have reason to complain[.]

Spring Place Kentish Town

Friday Evening —

JP thinks there must be some mistake in Mr D. calling on him as he has never heard of it —

About the same time, William Blake was appealing to Parker for his professional opinion. He wrote to Hayley on 22 June 1804 about the prices Hayley should expect to have to pay for engravings in his life of Romney:

it is not only my opinion but that of Mr Flaxman & Mr Parker both of whom I have consulted that to give a true Idea of Romneys Genius nothing less than Some Finishd Engravings will do, as Outline intirely omits his chief beauties. . . . Mr Parker whose Eminence as an Engraver makes his opinion deserve notice has advised, that 4 should be done in the highly finished manner & 4 in a less Finishd — & on my desiring him to tell me for what he Would undertake to engrave One in Each manner the size to be about 7 Inches by 5 ¼ which is the size of a Quarto printed Page, he answered: '30 guineas the finishd, & half the sum for the less finishd: but as you tell me that they will be wanted in November I am of opinion that if Eight different Engravers are Employd the Eight Plates will not be done by that time; as for myself [Note Parker now speaks] I have to day turned away a Plate of 400 Guineas because I am too full of work to undertake it, & I know that all the Good Engravers are so Engaged that they will be hardly prevaild upon to undertake more than One of the Plates on so short a notice.' . . . The Price Mr Parker had affixd to each is Exactly what I myself had before concluded upon. . . .

My Head of Romney is in very great forwardness. Parker commends it highly.

And six months later, on 28 December 1804, Blake wrote again to Hayley about the price of his engraving of Romney's "The Shipwreck":

Others too were praising Parker at the time. Bryan Froughton Jr wrote to F. J. Du Roveray on 19 March 1805 that in the print for Pope's Essay on Man in Du Roveray's edition of Pope's Poetical Works (1804),

the engraver has copied too accurately the flimsy & shadowy manner that Stothard so frequently deviates into —

— I have also observed this defect even in so excellent an engraver as Parker whose abilities I have wished to have seen before employed in the decoration of your elegant editions, as well as Sharp, both of whom will (I understand from you) be employed in the Subjects from Homer [1805], these & more, especially those from Fuseli will require such bold & forceful stile as those artists, as well as Neagle, A. Smith & Bromley so eminently possess — indeed I cannot doubt that my expectations of them, however sanguine they may be will be realized — [32]

But Parker's engravings for Pope's Poetical Works were the last he ever engraved for Du Roveray, for "He died after a short illness, aged about forty-five [i.e., 55]".[33] According to the obituary of James Parker, in The Gentleman's Magazine, 75 (June 1805), 586, James Parker, "an eminent portrait and historical engraver", died on 20 May and was buried in St Clement Danes, and his fellow Governors of the Society of Engravers "attended him to the grave". One would like to think that his old fellow-apprentice and partner William Blake was also among those at the graveside.

Both Parker and Blake had been notable collectors of prints, though Parker's were by contemporaries and Blake's were by 16th-Century masters.[34] About two years after Parker's death and presumably on behalf of his widow there was published

A | CATALOGUE | OF A | Collection of PRINTS, | COMPRISING A NUMEROUS ASSEMBLAGE OF | Proofs & Etchings, | AFTER WESTALL, SMIRKE, STODHART, and Others, | Several Ditto by Old Masters; | [Gothic:] Drawings, | by Morland, Town, &c. | BOOKS, BOOKS of PRINTS, | AND SEVERAL CURIOUS MISCELLANEOUS ARTICLES. | Together with a valuable Collection of | COINS AND MEDALS, | chiefly Silver, in a high State of Preservation, many of them | very rare and curious — late the Property of | Mr. JAMES PARKER, Engraver, | [Gothic:] Deceased; | Which will be Sold by Auction, | By Mr [Thomas] Dodd, | At his Spacious Room, | No. 101, St. Martin's Lane, | On WEDNESDAY, Feburary 18th, 1807, | AND FOLLOWING EVENING, | At Six o'Clock precisely. <British Museum Department of Coins and Medals>

The 260 lots, described with wonderful vagueness, include:

- 157 Eighteen ditto [various prints], by Blake, Tomkins, Ryland, &c.

- 159 Six Circles, by Blake, in colours[35]

- 162 Seventeen, by J. Parker, proofs and etchings

- 198 Thirty-five sculptural, by Parker, proofs

- 202 Thirty of book plates, after Stodhart, Westall, Smirke, &c. by Parker, proofs

- 203 Thirty ditto, ditto, proofs and etchings

- 204 Thirty ditto

- 205 [ — 208] Ditto

- 209 Ditto to Boydell's Shakspeare and Bowyer's History of England, by Parker

- 210 Ditto, proofs and etchings

- 211 [ — 214] Ditto, ditto

- 215 Twenty ditto, fine

- 216 [ — 217] Ditto, ditto

- 218 Twenty-five ditto, choice

- copper plates

- 235 Eight, Edwin and Angelina, &c. engraved by Parker

- 236 One, View of Claybrook Church, in aquatinta, by ditto, and the only print executed by him in this method.

Probably no sale since that time has included so many engravings by Parker — or so many copies of the prints Blake had engraved for the firm of Parker & Blake.

It is possible to make some very rough comparisons between the careers of James Parker and William Blake as engravers. In terms of commercial engravings[36] finished in each year, the pattern is:

| Year | Parker | Blake |

| unknown | 9 | -- |

| 1780 | 1 | 3 |

| 1781 | 1 | 11 |

| 1782 | 1 | 19 |

| 1783 | 3 | 16 |

| 1784 | 1 | 8 |

| 1785 | 1 | 1 |

| 1786 | 3 | 1 |

| 1787 | 2 | 1 |

| 1788 | 1 | 5 |

| 1789 | 1 | 2 |

| 1790 | -- | -- |

| 1791 | -- | 17 |

| 1792 | 6 | 9 |

| Year | Parker | Blake |

| 1793 | 7+ | 5 |

| 1794 | 11 | 6 |

| 1795 | 8[*] | 6 |

| 1796 | 12[*]+ | 25[**] |

| 1797 | 7[*]+ | 32[**] |

| 1798 | 1[*] | -- |

| 1799 | 4[*] | 4[*] |

| 1800 | 3[*] | 5 |

| 1801 | 3[*] | 1 |

| 1802 | 6[*]+ | 18 |

| 1803 | 2[*] | 6 |

| 1804 | 3[*] | 5 |

| 1805 | 31[*]+ | 8 |

| TOTAL | 136+ | 224 |

In comparing these totals, however, one must remember in the first place that engravings by Blake have been assiduously sought since 1861, and most of his plates have probably already been discovered, whereas this, the first record of Parker's engravings, is certainly incomplete.

And in the second place, Parker was probably on the average better remunerated than Blake for his engravings. For his octavo plates, Parker was often paid £8.8.0 or £10.10.0 (Hayley, Old Maids [1793], Armstrong, Preserving Health [1795], Green, The Spleen [1796], Somervile, The Chace [1796], and Collins, Poetical Works [1802]), which was probably about what Blake was paid for similar work, and we know that they were paid £5.5.0 for each plate they engraved in outline for Flaxman's Iliad (1805). However, Parker

On the other hand, Blake made only one plate for the Shakspeare and none at all for Hume. Further, Blake's own great series of folio plates for Young's Night Thoughts (1797) were made chiefly for glory rather than for cash — we do not know what he was paid for his folio Night Thoughts engravings, but for his 537 folio Night Thoughts drawings he was paid only £21.[39] While Parker was being entrusted with more responsible and remunerative folio plates, Blake was largely restricted to plates of smaller dimensions and value — and in 1800 he moved to a country village far from the booksellers who had such commissions in their gift. For most of his commercial folio plates, those for the Night Thoughts, Blake was probably paid only a small fraction of what Parker was receiving for work of similar size.

Of course, the differences between James Parker and William Blake are far more important than the similarities, and Blake had modest sources of income to which Parker had no access. Blake had a small but significant and steady income as a painter in water-colours, and he invented a method of Illuminated Printing in which all his published poetry appeared — though apparently no one else has ever used it — and from it he derived some income, though probably less than his time was worth as a professional engraver. And of course Blake was a genius as a painter and a poet. Not only that, but his greatest accomplishments in engraving, such as his Illustrations of The Book of Job (1826) and Dante, were far beyond anything James Parker achieved or attempted.

Blake was a solitary visionary, who did not join with others, who did not vote, who went his own way, content with his visions and his genius. The only collaboration he attempted with another man, in the firm of Parker & Blake, collapsed after only a few months. By contrast, James Parker worked very well in harness, he was a worthy and reliable member of his profession, and indeed he proved himself to be a leader in the organization of his fellow engravers. The two men were extraordinarily different — but clearly they were good friends. Today, the senior partner of the firm of Parker & Blake is scarcely known, whereas the junior member is famous wherever English is spoken.

The career of James Parker demonstrates what that of William Blake might have been like had he been a steady, reliable workman like Parker — and had he not been a genius.

| | ||