3. III.

What was the appearance and character of the actual individual?

What manner of personages were “Mosby and his

men,” as they really lived, and moved, and had their being in

the forests and on the hills of Fauquier, in Virginia, in the years

1863 and 1864? If the reader will accompany me, I will conduct

him to this beautiful region swept by the mountain winds,

and will introduce him—remember, the date is 1864—to a plain

and unassuming personage clad in gray, with three stars upon

his coat-collar, and two pistols in his belt.

He is slender, gaunt, and active in figure; his feet are small,

and cased in cavalry boots, with brass spurs; and the revolvers

in his belt are worn with an air of “business” which is unmistakable.

The face of this person is tanned, beardless, youthful-looking,

and pleasant. He has white and regular teeth, which

his habitual smile reveals. His piercing eyes flash out from

beneath his brown hat, with its golden cord, and he reins in his

horse with the ease of a practised rider. A plain soldier, low

and slight of stature, ready to talk, to laugh, to ride, to oblige

you in any way—such was Mosby, in outward appearance.

Nature had given no sign but the restless, roving, flashing eye,

that there was much worth considering beneath. The eye did

not convey a false expression. The commonplace exterior of

the partisan concealed one of the most active, daring, and penetrating

minds of an epoch fruitful in such. Mosby was born to

be a partisan leader, and as such was probably greater than any

other who took part in the late war. He had by nature all the

qualities which make the accomplished ranger; nothing could

daunt him; his activity of mind and body—call it, if you choose,

restless, eternal love of movement—was something wonderful;

and that untiring energy which is the secret of half the great

successes of history, drove him incessantly to plan, to scheme, to

conceive, and to execute. He could not rest when there was

anything to do, and scouted for his amusement, charging pickets

solus by way of sport. On dark and rainy nights, when other

men aim at being comfortably housed, Mosby liked to be moving

with a detachment of his men to surprise and attack some

Federal camp, or to “run in” some picket, and occasion consternation,

if not inflict injury.

The peculiar feature of his command was that the men occupied

no stated camp, and, in fact, were never kept together

except on an expedition. They were scattered throughout the

country, especially among the small farm-houses in the spurs of

the Blue Ridge; and here they lived the merriest lives imaginable.

They were subjected to none of the hardships and privations

of regular soldiers. Their horses were in comfortable

stables, or ranged freely over excellent pastures; the men lived

with the families, slept in beds, and had nothing to do with

“rations” of hard bread and bacon. Milk, butter, and all the

household luxuries of peace were at their command; and not

until their chief summoned them did they buckle on their arms

and get to horse. While they were thus living on the fat of the

land, Mosby was perhaps scouting off on his private account,

somewhere down toward Manassas, Alexandria, or Leesburg.

If his excursions revealed an opening for successful operations,

he sent off a well mounted courier, who travelled rapidly to the

first nest of rangers; thence a fresh courier carried the summons

elsewhere; and in a few hours twenty, thirty, or fifty men,

excellently mounted, made their appearance at the prescribed

rendezvous. The man who disregarded or evaded the second

summons to a raid was summarily dealt with; he received a note

for delivery to General Stuart, and on reaching the cavalry headquarters

was directed to return to the company in the regular

service from which he had been transferred. This seldom happened,

however. The men were all anxious to go upon raids,

to share the rich spoils, and were prompt at the rendezvous.

Once assembled, the rangers fell into column, Mosby said

“Come on,” and the party set forward upon the appointed

task—to surprise some camp, capture an army train, or ambush

some detached party of Federal cavalry out on a foraging expedition.

Such a life is attractive to the imagination, and the men came

to have a passion for it. But it is a dangerous service. It may

with propriety be regarded as a trial of wits between the opposing

commanders. The great praise of Mosby was, that his

superior skill, activity, and good judgment gave him almost

uninterrupted success, and invariably saved him from capture.

An attack upon Colonel Cole, of the Maryland cavalry, near

Loudon Heights, in the winter of 1863-64, was his only serious

failure; and that appears to have resulted from a disobedience

of his orders. He had here some valuable officers and men

killed. He was several times wounded, but never taken. On

the last occasion, in 1864, he was shot through the window of a

house in Fauquier, but managed to stagger into a darkened

room, tear off his stars, the badges of his rank, and counterfeit

a person mortally wounded. His assailants left him dying, as

they supposed, without discovering his identity; and when they

did discover it and hurried back, he had been removed beyond

reach of peril. After his wounds he always reappeared paler

and thinner, but more active and untiring than ever. They

only seemed to exasperate him, and make him more dangerous

to trains, scouting parties, and detached camps than before.

The great secret of his success was undoubtedly his unbounded

energy and enterprise. General Stuart came finally to repose

unlimited confidence in his resources, and relied implicitly upon

him. The writer recalls an instance of this in June, 1863.

General Stuart was then near Middleburg, watching the United

States army—then about to move toward Pennsylvania—but

could get no accurate information from his scouts. Silent, puzzled,

and doubtful, the General walked up and down, knitting

his brows and reflecting, when the lithe figure of Mosby appeared,

and Stuart uttered an exclamation of relief and satisfaction.

They were speedily in private consultation, and Mosby

only came out again to mount his quick gray mare and set out,

in a heavy storm, for the Federal camps. On the next day he

returned with information which put the entire cavalry in motion.

He had penetrated General Hooker's camps, ascertained

everything, and safely returned. This had been done in his

gray uniform, with his pistols at his belt—and I believe it was

on this occasion that he gave a characteristic evidence of his

coolness. He had captured a Federal cavalry-man, and they

were riding on together, when suddenly they struck a column of

the enemy's cavalry passing. Mosby drew his oil-cloth around

him, cocked his pistol, and said to his companion, “If you make

any sign or utter a word to have me captured, I will blow your

brains out, and trust to the speed of my horse to escape. Keep

quiet, and we will ride on without troubling anybody.” His

prisoner took the hint, believing doubtless that it was better to

be a prisoner than a dead man; and after riding along carelessly

for some distance, as though he were one of the column, Mosby

gradually edged off, and got away safely with his prisoner.

But the subject beguiles us too far. The hundreds of adventures

in which Mosby bore his part must be left for that extended

record which will some day be made. My chief object in this

brief paper has been to anticipate the sanguinary historians of

the “Lieutenant Colonel—” order; to show that Colonel

Mosby was no black-browed ruffian, but a plain, unassuming

officer of partisans, who gained his widely-extended reputation

by that activity and energy which only men of military ability

possess. This information in regard to the man is intended, as

I have said, for Northern readers of fairness and candour; for

that class who would not willingly do injustice even to an adversary.

In Virginia, Mosby is perfectly well known, and it would

be unnecessary to argue here that the person who enjoyed the

respect and confidence of Lee, Stuart, and Jackson, was worthy

of it. Mosby was regarded by the people of Virginia in his

true light as a man of great courage, decision, and energy, who

embarked like others in a revolution whose principles and

objects he fully approved. In the hard struggle he fought

bravely, exposed his person without stint, and overcame his

opponents by superior military ability. To stigmatize him as a

ruffian because he was a partisan is to throw obloquy upon the

memory of Marion, Sumter, and Harry Lee, of the old Revolution.

As long as war lasts, surprise of an enemy will continue

to be a part of military tactics; the destruction of his trains,

munitions, stores, and communications, a legitimate object of

endeavour. This Mosby did with great success, and he had no

other object in view. The charge that he fought for plunder is

singularly unjust. The writer of this is able to state of his own

knowledge that Colonel Mosby rarely appropriated anything to

his own use, unless it were arms, a saddle, or a captured horse,

when his own was worn out; and to-day, the man who captured

millions in stores and money is poorer than when he

entered upon the struggle.

This paper, written without the knowledge of Colonel Mosby,

who is merely an acquaintance of the writer, and intended as a

simple delineation of the man, has, in some manner, assumed the

form of an apology for the partisan and his career. He needs

none, and can await without fear that verdict of history which

the late President of the United States justly declared “could

not be avoided.” In the pages which chronicle the great struggle

of 1862, 1863, and 1864, Colonel Mosby will appear in his

true character as the bold partisan, the daring leader of cavalry,

the untiring, never-resting adversary of the Federal forces invading

Virginia. The burly-ruffian view of him will not bear

inspection; and if there are any who cannot erase from their

minds this fanciful figure of a cold, coarse, heartless adventurer,

I would beg them to dwell for a moment upon a picture which

the Richmond correspondent of a Northern journal drew the

other day.

On a summer morning a solitary man was seen beside the

grave of Stuart, in Hollywood Cemetery, near Richmond. The

dew was on the grass, the birds sang overhead, the green hillock

at the man's feet was all that remained of the daring leader of

the Southern cavalry, who, after all his toils, his battles, and the

shocks of desperate encounters, had come here to rest in peace.

Beside this unmarked grave the solitary mourner remained long,

pondering and remembering. Finally he plucked a wild flower,

dropped it upon the grave, and with tears in his eyes, left the

place.

This lonely mourner at the grave of Stuart was Mosby.

[ILLUSTRATION]

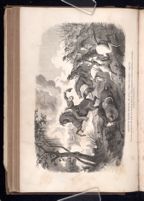

DEATH OF MAJOR PELHAM, (OF ALA.,) “THE GALLANT.”—Page 127.

“He was waving his hat aloft, and cheering them on, when a fragment of shell struck him in the head,

mortally wounding him.”

[Description: 521EAF. Illustration page, which depicts the death of Major Pelham. He is on his horse, with a mass of Confederate soldiers behind him and Union soldiers in the distant background, and is waving his hat in the air. His horse is rearing and Pelham is falling backwards as he has been hit by a shell fragment.]