| Wearing of the gray | ||

IV.

ASHBY.

1. I.

In the Valley of Virginia, the glory of two men outshines

that of all others; two figures were tallest, best beloved, and to-day

are most bitterly mourned. One was Jackson, the other

Ashby. The world knows all about Jackson, but has little

knowledge of Ashby. I was reading a stupid book the

other day in which he was represented as a guerilla—almost as

a robber and highwayman. Ashby a guerilla!—that great,

powerful, trained, and consummate fighter of infantry, cavalry,

and artillery, in the hardest fought battles of the Valley campaign!

Ashby a robber and highwayman!—that soul and perfect

mirror of chivalry! It is to drive away these mists of stupid or

malignant scribblers that the present writer designs recording

here the actual truth of Ashby's character and career. Apart

from what he performed, he was a personage to whom attached

and still attaches a never-dying interest. His career was all

romance—it was as brief, splendid, and evanescent as a dream—

but, after all, it was the man Turner Ashby who was the real

attraction. It was the man whom the people of the Shenandoah

Valley admire, rather than his glorious record. There was something

grander than the achievements of this soldier, and that was

the soldier himself.

Ashby first attracted attention in the spring of 1862, when

Jackson made his great campaign in the Valley, crushing one

after another Banks, Milroy, Shields, Fremont, and their associates.

Among the brilliant figures, the hard fighters grouped

Ashby was perhaps the most notable and famous. As the great

majority of my readers never saw the man, a personal outline

of him here in the beginning may interest. Even on this

soil there are many thousands who never met that model chevalier

and perfect type of manhood. He lives in all memories and

hearts, but not in all eyes.

What the men of Jackson saw at the head of the Valley

cavalry in the spring of 1862, was a man rather below the middle

height, with an active and vigorous frame, clad in plain Confederate

gray. His brown felt hat was decorated with a black

feather; his uniform was almost without decorations: his cavalry

boots, dusty or splashed with mud, came to the knee; and around

his waist he wore a sash and plain leather belt, holding pistol

and sabre. The face of this man of thirty or a little more, was

noticeable. His complexion was as dark as that of an Arab;

his eyes of a deep rich brown, sparkled under well formed

brows; and two thirds of his face was covered by a huge black

beard and moustache; the latter curling at the ends, the former

reaching to his breast. There was thus in the face of the

cavalier something Moorish and brigandish; but all idea of a

melodramatic personage disappeared as you pressed his hand,

looked into his eyes, and spoke to him. The brown eyes, which

would flash superbly in battle, were the softest and most friendly

imaginable; the voice, which could thrill his men as it rang like

a clarion in the charge, was the perfection of mild courtesy. He

was as simple and “friendly” as a child in all his words, movements,

and the carriage of his person. You could see from his

dress, his firm tread, his open and frank glance, that he was a

thorough soldier—indeed he always “looked like work”—but

under the soldier, as plainly was the gentleman. Such in his

plain costume, with his simple manner and retiring modesty,

was Ashby, whose name and fame, a brave comrade has truly

said, will endure as long as the mountains and valleys which he

defended.

2. II.

The achievements of Ashby can be barely touched on here—

history will set them in its purest gold. The pages of the splendid

record can only be glanced at now; months of fighting

must here be summed up and dismissed in a few sentences.

To look back to his origin—that always counts for something

—he was the son of a gentleman of Fauquier, and up to 1861

was only known as a hard rider, a gay companion, and the

kindest-hearted of friends. There was absolutely nothing in the

youth's character, apparently, which could detach him from the

great mass of mediocrities; but under that laughing face, that

simple, unassuming manner, was a soul of fire—the unbending

spirit of the hero, and no less the genius of the born master of

the art of war. When the revolution broke out Ashby got in

the saddle, and spent most of his time therein until he fell. It

was at this time—on the threshold of the war—that I saw him

first. I have described his person—his bearing was full of a

charming courtesy. The low, sweet voice made you his friend

before you knew it; and so modest and unassuming was his

demeanour that a child would instinctively have sought his side

and confided in him. The wonder of wonders to me, a few

months afterwards, was that this unknown youth, with the simple

smile, and the retiring, almost shy demeanour, had become

the right hand of Jackson, the terror of the enemy, and had

fallen near the bloody ground of Port Republic, mourned by

the whole nation of Virginia.

Virginia was his first and last love. When he went to Harper's

Ferry in April, 1861, with his brother Richard's cavalry

company, some one said: “Well, Ashby, what flag are we going

to fight under—the Palmetto, or what?” Ashby took off his

hat, and exhibited a small square of silk upon which was

painted the Virginia shield—the Virgin trampling on the tyrant.

“That is the flag I intend to fight under,” was his reply; and

he accorded it his paramount fealty to the last. Soon after this

incident active service commenced on the Upper Potomac; and

His brother Richard, while on a scout near Romney, with a

small detachment, was attacked by a strong party of the enemy,

his command dispersed, and as he attempted to leap a “cattlestop”

in the railroad, his horse fell with him. The enemy

rushed upon him, struck him cruelly with their sabres, and

killed him before he could rise. Ashby came up at the moment,

and with eight men charged them, killing many of them with

his own hand. But his brother was dead—the man whom he

had loved more than his own life; and thereafter he seemed like

another man. Richard Ashby was buried on the banks of the

Potomac—his brother nearly fainted at the grave; then he went

back to his work. “Ashby is now a devoted man,” said one

who knew him; and his career seemed to justify the words.

He took command of his company, was soon promoted to the

rank of a field officer, and from that moment he was on the track

of the enemy day and night. Did private vengeance actuate

the man, once so kind and sweet-tempered? I know not; but

something from this time forward seemed to spur him on to

unflagging exertion and ceaseless activity. Day and night he

was in the saddle. Mounted upon his fleet white horse, he would

often ride, in twenty-four hours, along seventy miles of front,

inspecting his pickets, instructing his detachments, and watching

the enemy's movements at every point. Here to-day, to-morrow

he would be seen nearly a hundred miles distant. The lithe

figure on the white horse “came and went like a dream,” said

one who knew him at that time. And when he appeared it was

almost always the signal for an attack, a raid, or a “scout,” in

which blood would flow.

In the spring of 1862, when Jackson fell back from Winchester,

Ashby, then promoted to the rank of Colonel, commanded

all his cavalry. He was already famous for his wonderful

activity, his heroic courage, and that utter contempt for danger

which was born in his blood. On the Potomac, near Shepherdstown,

he had ridden to the top of a crest, swept by the hot fire

of the enemy's sharpshooters near at hand; and pacing slowly

up and down on his milk-white horse, looked calmly over his

He was now to give a proof more striking still of his fearless

nerve. Jackson slowly retired from Winchester, the cavalry

under Ashby bringing up the rear, with the enemy closely pressing

them. The long column defiled through the town, and

Ashby remained the last, sitting his horse in the middle of Loudoun

street as the Federal forces poured in. The solitary horseman,

gazing at them with so much nonchalance, was plainly seen

by the Federal officers, and two mounted men were detached to

make a circuit by the back streets, and cut off his retreat.

Ashby either did not see this manœuvre, or paid no attention to

it. He waited until the Federal column was nearly upon him,

and had opened a hot fire—then he turned his horse, waved his

hat around his head, and uttering a cheer of defiance, galloped

off. All at once, as he galloped down the street, he saw before

him the two cavalrymen sent to cut off and capture him. To a

man like Ashby, inwardly chafing at being compelled to retreat,

no sight could be more agreeable. Here was an opportunity to

vent his spleen; and charging the two mounted men, he was soon

upon them. One fell with a bullet through his breast; and,

coming opposite the other, Ashby seized him by the throat,

dragged him from his saddle, and putting spur to his horse, bore

him off. This scene, which some readers may set down for

romance, was witnessed by hundreds both of the Confederate and

the Federal army.

During Jackson's retreat Ashby remained in command of the

rear, fighting at every step with his eavalry and horse artillery,

under Captain Chew. It was dangerous to press such a man.

His sharp claws drew blood. As the little column retired sullenly

up the valley, fighting off the heavy columns of General

Banks, Ashby was in the saddle day and night, and his guns

were never silent. The infantry sank to sleep with that thunder

in their ears, and the same sound was their reveille at dawn.

Weary at last of a proceeding so unproductive, General Banks

ceased the pursuit and fell back to Winchester, when Ashby

pursued in his turn, and quickly sent intelligence to Jackson,

which brought him back to Kernstown. The battle there fol

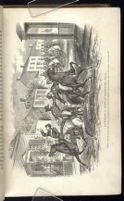

ADVENTURE OF ASHBY AT WINCHESTER.—Page 74.

Ashby seized him by the throat, dragged him from his saddle, and putting spur to his horse, bore him off.

[Description: 521EAF. Illustration page, which depicts General Ashby seizing a Union officer off of his horse by the neck. There is a soldier in front of Ashby, who is trying not to fall off of his horse as Ashby runs into him with his steed. The other soldier is so shocked at being jerked by the throat that he is simply falling forward towards Ashby. In the background a group of Union soldiers is arriving.]

invincible ardour, flanking the Federal forces, and nearly getting

in their rear. When Jackson was forced to retire, he again held

the rear; and continued in front of the enemy, eternally skirmishing

with them, until Jackson again advanced to attack

General Banks at Strasburg and Winchester. It was on a bright

May morning that Ashby, moving in front, struck the Federal

column of cavalry in transitu north of Strasburg, and scattered

them like a hurricane. Separated from his command, but bursting

with an ardour which defied control, he charged, by himself,

about five hundred Federal horsemen retreating in disorder,

snatched a guidon from the hands of its bearer, and firing right

and left into the column, summoned the men to surrender.

Many did so, and the rest galloped on, followed by Ashby, to

Winchester, where he threw the guidon, with a laugh, to a

friend, who afterwards had it hung up in the Library of the

Capitol at Richmond.

3. III.

The work of Ashby then began in earnest. The affair with

General Banks was only a skirmish—the wars of the giants followed.

Jackson, nearly hemmed in by bitter and determined foes,

fell back to escape destruction, and on his track rushed the

heavy columns of Shields and Fremont, which, closing in at

Strasburg and Front Royal, were now hunting down the lion.

It was then and there that Ashby won his fame as a cavalry

officer, and attached to every foot of ground over which he

fought some deathless tradition. The reader must look elsewhere

for a record of those achievements. Space would fail me

were I to touch with the pen's point the hundredth part of that

splendid career. On every hill, in every valley, at every bridge,

Ashby thundered and lightened with his cavalry and artillery.

Bitterest of the bitter was the cavalier in those moments; a man

sworn to hold his ground or die. He played with death, and

dared it everywhere. From every hill came the roar of his guns

as he loved it—and he did love it with all his soul—was less

sweet to him than the clash of sabres. It was in hand-to-hand

fighting that he seemed to take the greatest pleasure. In front

of his column, sweeping forward to the charge, Ashby was

“happy.” Coming to the Shenandoah near Newmarket, he

remained behind with a few men to destroy the bridge, and here

took place an event which may seem too trifling to be recorded,

but which produced a notable effect upon the army. While

retreating alone before a squadron of the enemy's cavalry in

hot pursuit of him, his celebrated white horse was mortally

wounded. Furious at this, Ashby cut the foremost of his assailants

out of the saddle with his sabre, and safely reached his

command; but the noble charger was staggering under him, and

bleeding to death. He dismounted, caressed for an instant, without

speaking, the proud neck, and then turned away. The historic

steed was led off to his death, his eyes glaring with rage it

seemed at the enemy still; and Ashby returned to his work,

hastening to meet the fatal bullet which in turn was to strike

him. The death of the white horse who had passed unscathed

through so many battles, preceded only by a few days that of

his rider, whom no ball had ever yet touched. It was on the

4th or 5th of June, just before the battle of Cross Keys, that

he ambuscaded and captured Sir Perey Wyndham, commander

of Fremont's cavalry advance. Sir Percy had publicly announced

his intention to “bag Ashby;” but unwarily advancing

upon a small decoy in the road, he found himself suddenly

attacked in flank and rear by Ashby in person; and he and his

squadron of sixty or seventy men were taken prisoners. That

was the last cavalry fight in which the great leader took part.

His days were numbered—death had marked him. But to the

last he was what he had always been, unresting, fiery, ever on

the enemy's track; and he died in harness. It was on the very

same evening, I believe, that while commanding the rear-guard

of Jackson, he formed the design of flanking and attacking

the enemy's infantry, and sent to Jackson for troops. A brave

associate, Colonel Bradley Johnson, described him at that moment,

head of the column with General Ewell, his black face in a blaze

of enthusiasm. Every feature beamed with the joy of the soldier.

He was gesticulating and pointing out the country and

position to General Ewell. I could imagine what he was saying

by the motions of his right arm. I pointed him out to my

adjutant—`Look at Ashby! see how he is enjoying himself!' ”

The moment had come. With the infantry, two regiments sent

him by Jackson, he made a rapid detour to the right, passed

through a field of waving wheat, and approached a belt of woods

upon which the golden sunshine of the calm June evening slept

in mellow splendour. In the edge of this wood Colonel Kane,

of the Pennsylvania “Bucktails,” was drawn up, and soon the

crash of musketry resounded from the bushes along a fence on

the edge of the forest, where the enemy were posted. Ashby

rushed to the assault with the fiery enthusiasm of his blood.

Advancing at the head of the Fifty-eighth Virginia in front,

while Colonel Johnson with the Marylanders attacked the enemy

in flank, he had his horse shot under him, but sprang up,

waving his sword, and shouting, “Virginians, charge!” These

words were his last. From the enemy's line, now within fifty

yards, came a storm of bullets; one pierced his breast, and he

fell at the very moment when the Bucktails broke, and were

pursued by the victorious Southerners. Amid that triumphant

shout the great soul of Ashby passed away. Almost before his

men could raise him he was dead. He had fallen as he wished

to fall—leading a charge, in full war harness, fighting to the last.

Placed on a horse in front of a cavalryman, his body was borne

out of the wood, just as the last rays of sunset tipped with fire

the foliage of the trees; and as the form of the dead chieftain

was borne along the lines of infantry drawn up in column,

exclamations broke forth, and the bosoms of men who had

advanced without a tremor into the bloodiest gulfs of battle,

were shaken by uncontrollable sobs. The dead man had become

their beau-ideal of a soldier; his courage, fire, dash, and unshrinking

nerve had won the hearts of these rough men; and now

when they read upon that pale face the stamp of the hand of

June evening was a mockery. That sunset was the glory which

fell on the soldier's brow as he passed away. Never did day

light to his death a nobler spirit.

4. IV.

Mere animal courage is a common trait. It was not the chief

glory of this remarkable man that he cared nothing for peril,

daring it with an utter recklessness. Many private soldiers of

whom the world never heard did as much. The supremely beautiful

trait of Ashby was his modesty, his truth, his pure and

knightly honour. His was a nature full of heroism, chivalry, and

simplicity; he was not only a great soldier, but a chevalier,

inspired by the prisca fides of the past. “I was with him,” said

a brave associate, “when the first blow was struck for the cause

which we both had so much at heart, and was with him in his

last fight, always knowing him to be beyond all modern men in

chivalry, as he was equal to any one in courage. He combined

the virtues of Sir Philip Sidney with the dash of Murat. His

fame will live in the valley of Virginia, outside of books, as

long as its hills and mountains shall endure.”

Never was truer comparison than that of Ashby to Murat and

Sidney mingled; but the splendid truth and modesty of the

great English chevalier predominated in him. The Virginian

had the dash and fire of Murat in the charge, nor did the glittering

Marshal at the head of the French cuirassiers perform

greater deeds of daring. But the pure and spotless soul of

Philip Sidney, that “mirror of chivalry,” was the true antetype

of Ashby's. Faith, honour, truth, modesty, a courtesy which

never failed, a loyalty which nothing could affect—these were

the great traits which made the young Virginian so beloved and

honoured, giving him the noble place he held among the men of

his epoch. No man lives who can remember a rude action of

his; his spirit seemed to have been moulded to the perfect shape

of antique courtesy; and nothing could change the pure gold

of his nature. His fault as a soldier was a want of discipline;

chief huntsman of a hunting party than a general—mingling

with his men in bivouac or around the camp fire, on a perfect

equality. But what he wanted in discipline and military rigour

he supplied by the enthusiasm which he aroused in the troops.

They adored him, and rated him before all other leaders. His

wish was their guide in all things; and upon the field they

looked to him as their war-king. The flash of his sabre as it

left the scabbard drove every hand to the hilt; the sight of his

milk-white horse in front was their signal for “attention,” and

the low clear tones of Ashby's order, “Follow me!” as he

moved to the charge, had more effect upon his men than a hundred

bugles.

I pray my Northern reader who does me the honour to peruse

this sketch, not to regard these sentences as the mere rhapsody

of enthusiasm. They contain the truth of Ashby, and those

who served with him will testify to the literal accuracy of the

sketch. He was one of those men who appear only at long intervals—a

veritable realization of the “hero” of popular fancy.

The old days of knighthood seemed to live again as he moved

before the eye; the pure faith of the earlier years was reproduced

and illustrated in his character and career. The anecdotes

which remain of his kindness, his courtesy, and warmth of

heart, are trifles to those who knew him, and required no such

proofs of his sweetness of temper and character. It is nothing

to such that when the Northern ladies about to leave Winchester,

came and said, “General Ashby, we have nothing contraband

about us—you can search our trunks and our persons;” he

replied, “The gentlemen of Virginia do not search ladies' trunks

or their persons, madam.” He made that reply because he was

Ashby. For this man to have been rude, coarse, domineering,

and insulting to unprotected ladies—as more than one Federal

general at Winchester was—that was simply impossible. He

might have said, in the words of the old Ulysses, “They live

their lives, I mine.”

Such was the private character, simple, beautiful, and “altogether

of dash, nerve, obstinacy, and daring never excelled. Behind

that sweet and friendly smile was the stubborn and reckless soul

of the born fighter. Under those brown eyes, as mild and gentle

as a girl's, was a brain of fire—a resolution of invincible

strength which dared to combat every adversary, with whatever

odds. His intellect, outside of his profession, was rather mediocre

than otherwise, and he wrote so badly that few of his productions

are worth preserving. But in the field he was a master

mind. His eye for position was that of the born soldier; and

he was obliged to depend upon that native faculty, for he had

never been to West Point or any other military school. They

might have improved him—they could not have made him.

God had given him the capacity to fight troops; and if the dictum

of an humble writer, loving and admiring him alive, and

now mourning him, be regarded as unreliable, take the words of

Jackson. That cool, taciturn, and unexcitable soldier never

gave praise which was undeserved. Jackson knew Ashby as

well as one human being ever knew another; and after the fall

of the cavalier he wrote of him, “As a partisan officer, I never

knew his superior. His daring was proverbial, his powers of

endurance almost incredible, his tone of character heroic, and

his sagacity almost intuitive in divining the purposes and movements

of the enemy.” The man who wrote these words—himself

daring, enduring, and heroic—had himself some sagacity in

“divining the purposes and movements of the enemy,” and

could recognise that trait in others.

The writer of this page had the honour to know the dead chief

of the Valley cavalry—to hear the sweet accents of his friendly

voice, and meet the friendly glance of the loyal eyes. It seems

to him now, as he remembers Ashby, that the hand he touched

was that of a veritable child of chivalry. Never did taint of

arrogance or vanity, of rudeness or discourtesy, touch that pure

and beautiful spirit. This man of daring so proverbial, of powers

of endurance so incredible, of character so heroic, and of a

sagacity so unfailing that it drew forth the praise of Jackson,

accomplished anything to make him famous. But famous he

was, and is, and will be for ever. The bitter struggle in which

he bore so noble a part has ended; the great flag under which

he fought is furled, and none are now so poor as to do it reverence.

But in failure, defeat, and ruin, this great name survives;

the cloud is not so black that the pure star of Ashby's fame

does not shine out in the darkness. In the memories and hearts

of the people of the Valley his glory is as fresh to-day as when

he fell. He rises up in memory, as once before the actual eye—

the cavalier on his milk-white steed, leading the wild charge, or

slowly pacing up and down defiantly, with proud face turned

over the shoulder, amid the bullets. Others may forget him—

we of the Valley cannot. For us his noble smile still shines as

it shone amid those glorious encounters of the days of Jackson,

when from every hill-top he hurled defiance upon Banks and

Fremont, and in every valley met the heavy columns of the

Federal cavalry, sabre to sabre. He is dead, but still lives.

That career—brief, fiery, crammed with glorious shocks, with

desperate encounters—is a thing of the past, and Ashby has

“passed like a dream away.” But it is only the bodies of such

men that die. All that is noble in them survives. What comes

to the mind now when we pronounce the name of Ashby, is

that pure devotion to truth and honour which shone in every

act of his life; that kind, good heart of his which made all love

him; that resolution which he early made, to spend the last

drop of his blood for the cause in which he fought; and the

daring beyond all words, which drove him on to combat whatever

force was in his front. We are proud—leave us that at

least—that this good knight came of the honest old Virginia

blood. He tried to do his duty; and counted toil, and danger,

and hunger, and thirst, and exhaustion, as nothing. He died as

he had lived, in harness, and fighting to the last. In an unknown

skirmish, of which not even the name is preserved, the

fatal bullet came; the wave of death rolled over him, and the

august figure disappeared. But that form is not lost in the

time dim the splendour of the good knight's shield. The figure

of Ashby, on his milk-white steed, his face in “a blaze of enthusiasm,”

his drawn sword in his hand—that figure will truly

live in the memory and heart of the Virginian as long as the

battlements of the Blue Ridge stand, and the Shenandoah flows.

| Wearing of the gray | ||