| CHAPTER XV.

I MEET A VISION. My wife and I, or, Harry Henderson's history | ||

15. CHAPTER XV.

I MEET A VISION.

“I SAY, Hal, do you want to get acquainted with

any of the P. G.'s here in New York? If you

do, I can put you on the track.”

“P. G.'s?” said I, innocently.

“Yes; you know that's what Plato calls pretty girls. I

don't believe you remember your Greek. I'm going out this

evening where there's a lot of 'em—splendid house on Fifth

avenue—lots of tin—girls gracious. Don't know which of

'em I shall take yet. Don't you want to go with me and

see?”

Jim stood at the looking-glass brushing his hair and arranging

his necktie.

“Jim Fellows, you are a coxcomb,” said I.

“I don't know why I shouldn't be,” said he. “The girls

fairly throw themselves at one's head. They are up to all

that sort of thing. Besides, I'm on the lookout for my fortune,

and it all comes in the way of business. Come, now,

don't sit there writing all the evening. Come out, and let

me show you New York by gaslight.”

“No,” said I; “I've got to finish up this article for the

Milky Way. The fact is, a fellow must be industrious to

make anything, and my time for seeing girls isn't come yet.

I must have something to support a wife on before I look

round in that direction.”

“The idea, Harry, of a good-looking fellow like you, not

making the most of his advantages! Why, there are nice

girls in this city that could help you up faster than all the

writing you can do these ten years. And you sitting, moiling

and toiling, when you ought to be making some lovely

woman happy!”

“I shall never marry for money, Jim, you may depend

upon that.”

“Bah, bah, black sheep,” said Jim. “Who is talking

about marrying for money? A fine girl is none the worse

for fifty thousand dollars, and I can give you a list of

twenty that you can go round among until you fall in love,

and not come amiss anywhere, if it's falling in love that

you want to do.”

“Oh, come, Jim,” said I, “do finish your toilet and be off

with yourself if you are going. I don't blame a woman who

marries for money, since the whole world has always agreed

to shut her out of any other way of gaining an independence.

But for a man, with every other avenue open to him, to

mouse about for a rich wife, I think is too dastardly for

anything.”

“That would make a fine point for a paragraph,” said Jim,

turning round to me, with perfect good humor. “So I advise

you to save it for the moral part of the paper. You see, if

you waste too much of that sort of thing on me, your mill

may run low. It's a deuced hard thing to keep the moral

agoing the whole year, you'll find.”

“Well,” said I, “I am going to try to make a home for a

wife, by good, thorough work, done just as work ought to be

done; and I have no time to waste on society in the meanwhile.”

“And when you are ready for her,” said Jim, “I suppose

you expect to receive her per `Divine Providence' Express,

ticketed and labeled, and expenses paid. Or, may be she'll

be brought to you some time by genii, as the Princess of

China was brought to the Prince of Tartary, when he was

asleep. I used to read about that in the Arabian tales.”

I give this little passage of my conversation with Jim, because

it is a pretty good illustration of the axiom, that “It

is not in man that walketh to direct his steps.” When we

have announced any settled purpose or sublime intention,

in regard to our future course of life, it seems to be the

delight of fortune to throw us directly into circumstances in

we never will do, and the fortunes of our lives turn upon

the most inconsiderable hinges.

Mine turned upon an umbrella.

The next morning I had business in the very lowermost

part of the city, and started off without my umbrella; but

being weather-wise, and discerning the face of the sky,

I went back to my room and took it. It was one of those

little pet objects of vertu, to which a bachelor sometimes

treats himself in lieu of domestic luxuries. It had a finely-carved

handle, which I bought in Dieppe, and which caused

it to be peculiar among all the umbrellas in New York.

It was one of those uncertain, capricious days that mark

the coming in of April, when Nature, like a nervous beauty,

doesn't seem to know her own mind, and laughs one moment

and cries the next with a perplexing uncertainty.

The first part of the morning the amiable and smiling

predominated, and I began to regret that I had encumbered

myself with the troublesome precaution of an umbrella

while tramping around down town. In this mood of mind

I sat at Fulton Ferry waiting the starting of the Bleecker

street car, when suddenly the scene was enlivened

to my view by the entrance of a young lady, who happened

to seat herself exactly opposite to me.

Now, as a writer, an observer of life and manners, I

had often made quiet studies of the fair flowers of modern

New York society as I rode up and down in the cars.

In no other country in the world, perhaps, has a man the

opportunity of being vis-à-vis with the best and most cultured

class of young women in the public conveyances. In

England, this class are veiled and secluded from gaze by

all the ordinances and arrangements of society. They go

out only in their own carriage; they travel in reserved

compartments of the railway carriages; they pass from

these to reserved apartments in the hotels, where they are

served apart in family privacy as much as in their own

dwellings. In France, a still stricter régime watches over the

young, unmarried girl, who is kept in the shade of an almost

dwellings. In France, a still stricter régime watches over the

young, unmarried girl, who is kept in the shade of an almost

conventual seclusion till marriage opens the doors of her

prison. The young American girl, however, of the better

and of the best classes, is to be met and observed everywhere.

She moves through life with the assured step of a

princess, too certain of her position and familiar with her

power even to dream of a fear. She looks on her surroundings

from above with the eye of a mistress, and expects, of

course, to see all things give way before her, as in our republican

society they generally do.

During the few months I had spent in New York I had

diligently kept out of society. The permitted silent acquaintance

with my fair countrywomen which I gained

while riding up and down the street conveyances, became,

therefore, a favorite and harmless source of amusement.

Not an item in the study escaped me, not a feather in that

rustling and wonderful plumage of fashion that bore them

up, was unnoted. I mused on styles, and characteristics,

and silently wove in my own mind histories to correspond

with the various physiognomies I studied. Let not the

reader imagine me staring point blank, with my mouth

open, at all I met. The art of noting without appearing to

note, of seeing without seeming to see, was one that I cultivated

with assiduity.

Therefore, without any impertinent scrutiny, satisfied

myself of the fact that a feminine presence of an unusual

kind and quality was opposite to me. It was, at first glance,

one of the New York princesses of the blood, accustomed to

treading on clouds and breathing incense. There was a

quiet savoir faire and self-possession as she sat down on her

seat, as if it were a throne; and there was a species of repressed

vitality and decision in all her little involuntary

movements that interested me as live things always do

interest, in proportion to their quantum of life. We all are

familiar with the fact that there are some people, who, let

quietly, nevertheless impress their personality on those

around them, and make their presence felt. An attraction

of this sort drew my eyes toward my neighbor. She was a

young lady of medium height, slender and elastic figure,

features less regularly beautiful than piquant and expressive.

I remarked a pair of fine dark eyes the more from the

contrast with a golden crêpe of hair. The combination of

dark eyes and lashes with fair hair, always produces effect

of a striking character. She was attired as became a

Fifth Avenue princess, who has the world of fashion at her

feet,—yet, to my thinking, as one who had chosen and

adapted her material with an eye of taste. A delicate

cashmere was folded carelessly round her shoulders, and

her little hands were gloved with a careful nicety of fit;

and dangling from one finger was a toy purse of gold and

pearl, in which she began searching for the change to pay

her fare. I saw, too, as she investigated, an expression of

perplexity, slightly tinged with the ludicrous, upon her face.

I perceived at a glance the matter. She was surveying a

ten-dollar note with a glance of amused vexation, and vainly

turning over her little purse for the smaller change or

tickets available in the situation. I leaned forward and

offered, as gentlemen generally do, to take her fare and

pass it forward. With a smile of apology she handed me

the bill, and showed the little empty purse. “Allow me

to arrange it,” I said. She smiled and blushed. I passed up

the ticket necessary for the occasion, returned her bill,

bowed, and immediately looked another way with sedulous

care.

It requires an extra amount of discretion and delicacy

to make it tolerable to a true lady to become in the smallest

degree indebted to a gentleman who is a stranger. I was

aware that my fair vis-à-vis was inwardly disturbed at

having inadvertently been obliged to accept from me even

so small an obligation as a fare ticket; but as matters were,

there was no help for it. On the whole, though I was sorry

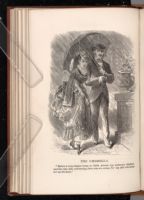

THE UMBRELLA.

"Before a very elegant house in Fifth Avenue my unknown alighted,

and the rain still continuing, there was an excuse for my still attending

her up the steps."

[Description: 467EAF. Image of Harry walking down Fifth Avenue with a beautiful woman. He is protecting her from the rain with his umbrella.]

good luck for myself. We rode along—perhaps each of us

conscious at times of being attentively considered by the

other, until the cars turned up Park Row before the Astor

House; she signalled the conductor to stop, and got out.

Here it was that the beneficent intentions of the fates, in

causing me to bring my umbrella, were made manifest.

Just as the car started again, came one of those sudden

gushes of rain with which perverse April delights to ruffle

and discompose unwary passengers. It was less a decent,

decorous shower, than a dash of water by the bucketful.

Immediately I jumped out and stepped to the side of my

gentle neighbor, begging her to allow me to hold my umbrella

over her, and see her in safety across Broadway. She

meant to have stopped at one or two places, she said, but it

rained so she would thank me to put her into a Fifth

Avenue stage. So we went together, threading our way

through rushing and trampling carriages, horses, and cars,

—a driving storm above, below, and around, which seemed

to throw my fair princess entirely upon my protection for

a few moments, till I had her safe in the up-town omnibus.

As it was my route, also, I, too, entered, and by this time

feeling a sort of privilege of acquaintance, arranged the

fare for her, and again received a courteous and apologetic

acknowledgment. Before a very elegant house in Fifth

Avenue my unknown alighted, and the rain still continuing,

there was an excuse for my attending her up the steps,

and ringing the door-bell for her.

We were kept waiting in this position several minutes,

when she very gracefully expressed her thanks for my

kindness, and begged that I would walk in.

Surprised and pleased, I excused myself on plea of engagements,

but presented her with my card, and said I

would do myself the pleasure of calling at another time.

With a little laugh and blush she handed me a card from

the tiny pearl and gold case, on which was engraved “Eva

Van Arsdel,” and in the corner, “Wednesdays.”

“We receive on Wednesdays, Mr. Henderson,” she said,

“and mamma will be so happy to make your acquaintance.”

Here the door opened, and my fairy princess vanished

from view, with a parting vision of a blush, smile, and bow,

and I was left outside with the rain and the mud and the

dull, commonplace grind of my daily work.

The house, as I noted it, was palatial in its aspect,

Clear, large windows, which seemed a single sheet of

crystal, gave a view of banks of flowering hyacinths,

daffodils, crocuses, and roses, curtained in by misty falls of

lace drapery. Evidently it was one of those Circean regions

of retreat, where the lovely daughters of fashionable

wealth in New York keep guard over an eternal lotus-eater's

paradise; where they trend on enchanted carpets,

move to the sound of music, and live among flowers and

odors a life of blissful ignorance of toil or care.

“To what purpose,” I thought to myself, “should I call

there, or pursue the vision into its own regions? æneas

might as well try to follow Venus to the scented regions

above Idalia, where her hundred altars forever burn, and

her flowers never die.”

But yet I was no wiser and no older than other men at

three-and-twenty, and the little card which I had placed

in my vest pocket seemed to diffuse an agreeable, electric

warmth, which constantly reminded me of its presence

there. I took it out and looked at it. I spelled the name

over, and dwelt on every letter. There was so much positive

character in the little lady,—such a sort of spicy, racy

individuality, that the little I had seen of her was like reading

the first page of an enchanting romance, and I could

not repress a curiosity to go on with it. To-day was Monday;

the reception day was Wednesday. Should I go?

Prudence said, “No; you are a young man with your way

to make; you are self-dependent; you are poor; you have

no time to spend in helping rich idle people to hunt butterflies,

and string rose-leaves, and make dandelion-chains.

If you set your foot over one of those enchanted thresholds,

enervated, and spoiled for any really high or severe

task-work; you will become an idler, a dangler; the

power of sustained labor and self-denial will depart from

you, and you will run like a breathless lackey after the

chariot of wealth and fashion.”

On the other hand, as the little bit of enchanted pasteboard

gently burned in my vest pocket, it said:

“Why should you be rude? It is incumbent on you as a

gentleman to respond to the invitation so frankly given.

Besides, the writer who aspires to influence society must

know society; and how can one know society unless one

studies it? A hermit in his cell is no judge of what is

going on in the world. Besides, he does not overcome the

world who runs away from it, but he who meets it bravely.

It is the part of a coward to be afraid of meeting wealth and

luxury and indolence on their own grounds. He really conquers

who can keep awake, walking straight through the

enchanted ground; not he who makes a detour to get

round it.'

All which I had arrayed in good set terms as I rode back

to my room, and went up to Bolton to look up in his library

the authorities for an article I was getting out on the Domestic

Life of the Ancient Greeks. Bolton had succeeded in

making me feel so thoroughly at home in his library that

it was to all intents and purposes as if it were my own.

As I was tumbling over the books that filled every corner,

there fell out from a little niche a photograph, or

rather ambrotype, such as were in use in the infancy of the

art. It fell directly into my hand, so that taking it up it

was impossible not to perceive what it was, and I recognized

in an instant the person. It was the head of my

cousin Caroline, not as I knew her now, but as I remembered

her years ago, when she and I went to the Academy

together.

It is almost an involuntary thing, on such occasions, to

exclaim, “Who is this?” But Bolton was so very reticent a

question. There are individuals who unite a great winning

and sympathetic faculty with great reticence. They

make you talk, they win your confidence, they are interested

in you, but they ask nothing from you, and they tell you

nothing. Bolton was all the while doing obliging things

for me and for Jim, but he asked nothing from us; and

while we felt safe in saying anything in the world before

him, and while we never felt at the moment that conversation

flagged, or that there was any deficiency in sympathy

and good fellowship on his part, yet upon reflection

we could never recall anything which let us into the interior

of his own life-history.

The finding of this little memento impressed me, therefore,

oddly,—as if a door had suddenly been opened into a

private cabinet where I had no right to look, or an open

letter which I had no right to read had been inadvertently

put into my hands. I looked round on Bolton, as he sat

quietly bending over a book that he was consulting, with

his pen in hand and his cat at his elbow; but the question I

longed to ask stuck fast in my throat, and I silently put

back the picture in its place, keeping the incident to ponder

in my heart. What with the one pertaining to myself, and

with the thoughts suggested by this, I found myself in a disturbed

state that I determined to resist by setting myself

a definite task of so many pages of my article.

In the evening, when Jim came in, I recounted my adventure

and showed him the card.

He surveyed it with a prolonged whistle. “Good now!”

he said; “the ticket sent by the Providence Express. I

see—”

“Who are these Van Arsdels, Jim?”

“Upper tens,” said Jim, decisively. “Not the oldest Tens,

but the second batch. Not the old Knickerbocker Vanderhoof,

and Vanderhyde, and Vanderhorn set that Washy

Irving tells about,—but the modern nobs. Old Van Arsdel

does a smashing importing business—is worth his millions

out, and one strong-minded sister who has retired from

the world, and isn't seen out anywhere. The one you saw

was Eva; they say she's to marry Wat Sydney,—the greatest

match there is going in New York. How do you say—shall

you go, Wednesday?”

“Do you know them?”

“Oh, yes. Alice Van Arsdel is a splendid girl, and we are

good friends, and I look in on them sometimes just to

give them the light of my countenance. They are always

after me to lead the German in their parties; but I've given

that up. Hang it all! it's too steep on a fellow that has to

work all day, with no let up, to be kept dancing till daylight

with those girls. It don't pay!”

“I should think not,” said I.

“You see,” pursued Jim, “these girls have nothing under

heaven to do, and when they've danced all night, they go to

bed and sleep till till eleven or twelve o'clock the next day

and get their rest; while we fellows have to be up and in

our offices at eight o'clock next morning. The fact is, it

may do for once or twice, but it knocks a fellow up pretty

fast. It's a bad thing for the fellows; they get to taking

wine and brandy and one thing or another to keep up, and

the Devil only knows what comes of it.”

“And are these Van Arsdels in that frivolous set?” said I.

“Well, you see they are not really frivolous, either;

they are nice girls, well educated, graduated at the Universal

Thingumbob College, where they teach girls everything

that ever has been heard of, before they are seventeen.

And then they have lived in Paris, and lived in Germany,

and lived in Italy, and picked up all the languages; so

that when they have anything to say they have a choice of

four languages to say it in.”

“And have they anything to say worth hearing in any of

the four?” said I.

“Well, yes, now, honor bright. There's Alice Van Arsdel:

she's ambitious as the devil, but, after all, a good, warmhearted

“And this lady?” said I, fingering the card.

“Eva? Well, she's had a great run; she's killing, as they

say, and she's pretty—no denying that; and, really, there's

a good deal to her,—like the sponge cake at the bottom of

the trifle, you know, with a good smart flavor of wine and

spice.”

“And she's engaged to— whom did you say?”

“Wat Sydney.”

“And what sort of a man is he?”

“What sort? why, he's a rich man; owns all sorts of

things,—gold mines in California, and copper mines in Lake

Superior, and salt works, and railroads. In fact, the thing

is to say what he doesn't own. Immense head for business,

—regular steel-trap to deal with,—has the snap of a pike.”

“Pleasing prospect for a domestic companion,” said I.

“Oh, as to that, I believe Wat is good-hearted enough to

his own folks. They say he is very devoted to his old

mother and a parcel of old maid aunts, and as he's rich, it's

thought a great virtue. Nobody sings my praises, I notice,

because I mind my mammy and Aunt Sarah. You see it

takes a million-power solar microscope to bring out fellows'

virtues.”

“Is the gentleman handsome?”

“Well, if he was poor, nobody would think much of

his looks. If he had, say, a hundred thousand or two, he

would be called fair to middling in looks. As it is, the girls

rave about him. He's been after Eva now for six months,

and the other girls are ready to tear her eyes out. But the

engagement hasn't come out yet. I think she's making up

her mind to him.”

“Not in love, then?”

“Well, she's been queen so long she's blasée and difficult,

and likes to play with her fish before she lands him. But of

course she must have him. Girls like that must have

money to keep 'em up; that's the first requisite. I tell you

the purple and fine linen of these princesses come to something.

where there's one better. Then she's been out three seasons.

There's Alice just come out, and Alice is a stunner,

and takes tremendously! And then there's Angeline, a

handsome, spicy little witch, smarter than either, that is

just fluttering, and scratching, and tearing her hair with

impatience to have her turn. And behind Angeline there's

Marie—she's got a confounded pair of eyes. So you see

there's no help for it; Miss Eva must abdicate and make

room for the next comer.”

“Well,” said I, “about this reception?”

“Oh! go, by all means,” said Jim. “It will be fun. I'll

go with you. You see it's Lent now, thank the stars! and

so there's no dancing,—only quiet evenings and lobster salad;

because, you see, we're all repenting of our sins and getting

ready to go at it again after Easter. A fellow now can go

to receptions, and get away in time to have a night's rest,

and the girls now and then talk a little sense between

whiles. They can talk sense when they like, though one

wouldn't believe it of 'em. Well, take care of yourself, my

son, and I'll take you round there on Wednesday evening.”

And Jim went whistling down the stairs, leaving me to finish

my article on the Domestic Manners of the Greeks.

I remember that very frequently that evening, while

stopping to consider how I should begin the next sentence,

I unconsciously embellished the margin of my manuscript

by writing “Eva, Eva, Eva Van Arsdel” in an absentminded,

mechanical way. In fact, from that time, that name

began often to obtrude itself on every bit of paper when I

tried my pen.

The question of going to the Wednesday evening reception

was settled in the affirmative. What was to hinder my

taking a look at fairy land in a purely philosophical spirit?

Nothing, certainly. If she were engaged she was nothing

to me,—never would be. So, clearly there was no danger.

| CHAPTER XV.

I MEET A VISION. My wife and I, or, Harry Henderson's history | ||