| CHAPTER XIII.

BACHELOR COMRADES. My wife and I, or, Harry Henderson's history | ||

13. CHAPTER XIII.

BACHELOR COMRADES.

I SOON became well acquainted with my collaborators

on the paper. It was a pleasant surprise to

be greeted in the foreground by the familiar face

of Jim Fellows, my old college class-mate.

Jim was an agreeable creature, born with a decided genius

for gossip. He had in perfection the faculty which phrenologists

call individuality. He was statistical in the very

marrow of his bones, apparently imbibing all the external

facts of every person and everything around him, by a kind

of rapid instinct. In college, Jim always knew all about

every student; he knew all about everybody in the little

town where the college was situated, their name, history,

character, business, their front door and their back door

affairs. No birth, marriage, or death ever took Jim by surprise;

he always knew all about it long ago.

Now, as a newspaper is a gossip market on a large scale,

this species of talent often goes farther in our modern literary

life than the deepest reflection or the highest culture.

Jim was the best-natured fellow breathing; it was impossible

to ruffle or disturb the easy, rattling, chattering

flow of his animal spirits. He was like a Frenchman in his

power of bright, airy adaptation to circumstances, and determination

and ability to make the most of them.

“How lucky!” he said, the morning I first shook hands

with him at the office of the Great Democracy; “you are

just on the minute; the very lodging you want has been

vacated this morning by old Styles; sunny room—south

windows—close by here—water, gas, and so on, all correct;

and, best of all, me for your opposite neighbor.”

I went round with him, looked, approved, and was settled

and activity of old college days. We had a rattling,

gay morning, plunging round into auction-rooms, bargaining

for second-hand furniture, and with so much zeal did

we drive our enterprise, seconded by the co-labors of a charwoman

whom Jim patronized, that by night I found myself

actually settled in a home of my own, making tea in Jim's

patent bachelor tea-kettle, and talking over his and my

affairs with the freedom of old cronies. Jim made no scruple

in inquiring in the most direct manner as to the terms

of my agreement with Mr. Goldstick, and opened the subject

succinctly, as follows:

“Now, my son, you must let your old grandfather advise

you a little about your temporalities. In the first

place; what's Old Soapy going to give you?”

“If you mean Mr. Goldstick,” said I—

“Yes,” said he, “call him `Soapy' for short. Did he

come down handsomely on the terms?”

“His offers were not as large as I should have liked; but

then, as he said, this paper is not a money-making affair,

but a moral enterprise, and I am willing to work for less.”

“Moral grandmother!” said Jim, in a tone of unlimited

disgust. “He be—choked, as it were. Why, Harry Henderson,

are your eye-teeth in such a retrograde state as that?

Why, this paper is a fortune to that man; he lives in a

palace, owns a picture gallery, and rolls about in his own

carriage.”

“I understood him,” said I, “that the paper was not

immediately profitable in a pecuniary point of view.”

“Soapy calls everything unprofitable that does not yield

him fifty per cent. on the money invested. Talk of moral

enterprise! What did he engage you for?”

I stated the terms.

“For how long?”

“For one year.”

“Well, the best you can do is to work it out now. Never

make another bargain without asking your grandfather.

am nothing at all of a writer compared to you. But then,

to be sure, I fill a place you've really no talent for.”

“What is that?”

“General professor of humbug,” said Jim. “No sort of

business gets on in this world without that, and I'm a real

genius in that line. I made Old Soapy come down, by

threatening to `rat,' and go to the Spouting Horn, and they

couldn't afford to let me do that. You see, I've been up

their back stairs, and know all their little family secrets.

The Spouting Horn would give their eye-teeth for me. It's

too funny,” he said, throwing himself back and laughing.

“Are these papers rivals?” said I.

“Well, I should `rayther' think they were,” said he, eyeing

me with an air of superiority amounting almost to contempt.

“Why, man, the thing that I'm particularly valuable for is,

that I always know just what will plague the Spouting

Horn folks the most. I know precisely where to stick a pin

or a needle into them; and one great object of our paper is

to show that the Spouting Horn is always in the wrong.

No matter what topic is uppermost, I attend to that, and

get off something on them. For you see, they are popular,

and make money like thunder, and, of course, that isn't to

be allowed. “Now,” he added, pointing with his thumb upward,

“overhead, there is really our best fellow—Bolton.

Bolton is said to be the best writer of English in our

day; he's an A No. 1, and no mistake; tremendously educated,

and all that, and he knows exactly to a shaving what's

what everywhere; he's a gentleman, too; we call him the

Dominie. Well, Bolton writes the great leaders, and fires

off on all the awful and solemn topics, and lays off the politics

of Europe and the world generally. When there's a

row over there in Europe, Bolton is magnificent on editorials.

You see, he has the run of all the rows they have had

there, and every bobbery that has been kicked up since the

Christian era. He'll tell you what the French did in 1700

splendidly on what's to turn up next.”

“I suppose they give him large pay,” said I.

“Well, you see, Bolton's a quiet fellow and a gentleman—

one that hates to jaw—and is modest, and so they keep him

along steady on about half what I would get out of them

if I were in his skin. Bolton is perfectly satisfied. If I

were he, I shouldn't be, you see. I say, Harry, I know

you'd like him. Let me bring him down and introduce

him,” and before I could either consent or refuse, Jim rattled

up stairs, and I heard him in an earnest, persuasive

treaty, and soon he came down with his captive.

I saw a man of thirty-three or thereabouts, tall, well

formed, with bright, dark eyes, strongly-marked features,

a finely-turned head, and closely-cropped black hair. He

had what I should call presence—something that impressed

me, as he entered the room, with the idea of a superior kind

of individuality, though he was simple in his manners,

with a slight air of shyness and constraint. The blood

flushed in his cheeks as he was introduced to me, and there

was a tremulous motion about his finely-cut lips, betokening

suppressed sensitiveness. The first sound of his voice, as he

spoke, struck on my ear agreeably, like the tones of a fine

instrument, and, reticent and retiring as he seemed, I felt

myself singularly attracted toward him.

What impressed me most, as he joined in the conversation

with my rattling, free and easy, good-natured neighbor,

was an air of patient, amused tolerance. He struck me as

a man who had made up his mind to expect nothing and ask

nothing of life, and who was sitting it out patiently, as one

sits out a dull play at the theater. He was disappointed

with nobody, and angry with nobody, while he seemed to

have no confidence in anybody. With all this apparent

reserve, he was simply and frankly cordial to me, as a newcomer

and a fellow-worker on the same paper.

“Mr. Henderson,” he said, “I shall be glad to extend to

you the hospitalities of my den, such as they are. If I can

me. Perhaps you would like to walk up and look at my

books? I shall be only too happy to put them at your disposal.”

We went up into a little attic room whose walls were literally

lined with books on all sides, only allowing space for

the two southerly windows which overlooked the city.

“I like to be high in the world, you see,” he said, with a

smile.

The room was not a large one, and the center was occupied

by a large table, covered with books and papers. A cheerful

coal-fire was burning in the little grate, a large leather arm-chair

stood before it, and, with one or two other chairs,

completed the furniture of the apartment. A small, lighted

closet, whose door stood open on the room, displayed a pallet

bed of monastic simplicity.

There were two occupants of the apartment who seemed

established there by right of possession. A large Maltese

cat, with great, golden eyes, like two full moons, sat gravely

looking into the fire, in one corner, and a very plebeian,

scrubby mongrel, who appeared to have known the hard

side of life in former days, was dozing in the other.

Apparently, these genii loci were so strong in their sense

of possession that our entrance gave them no disturbance.

The dog unclosed his eyes with a sleepy wink as we came

in, and then shut them again, dreamily, as satisfied that all

was right.

Bolton invited us to sit down, and did the honors of his

room with a quiet elegance, as if it had been a palace instead

of an attic. As soon as we were seated, the cat sprang

familiarly on the table and sat down cosily by Bolton, rubbing

her head against his coat-sleeve.

“Let me introduce you to my wife,” said Bolton, stroking

her head. “Eh. Jenny, what now?” he added, as she seized

his hands playfully in her teeth and claws. “You see, she

has the connubial weapons,” he said, “and insists on being

treated with attention; but she's capital company. I read

Puss soon stepped from her perch on the table and ensconced

herself in his lap, while I went round examining

his books.

The library showed varied and curious tastes. The books

were almost all rare.

“I have always made a rule,” he said, “never to buy a

book that I could borrow.”

I was amused, in the course of the conversation, at the

relations which apparently existed between him and Jim

Fellows, which appeared to me to be very like what might

be supposed to exist between a philosopher and a lively

pet squirrel—it was the perfection of quiet, amused tolerance.

Jim seemed to be not in the slightest degree under constraint

in his presence, and rattled on with a free and easy

slang familiarity, precisely as he had done with me.

“What do you think Old Soapy has engaged Hal for?”

he said. “Why, he only offers him—” Here followed the

statement of terms.

I was annoyed at this matter-of-fact way of handling

my private affairs, but on meeting the eyes of my new

friend I discerned a glance of quiet humor which re-assured

me. He seemed to regard Jim only as another form of the

inevitable.

“Don't you think it is a confounded take-in?” said Jim.

“Of course,” said Mr. Bolton, with a smile, “but he will

survive it. The place is only one of the stepping-stones.

Meanwhile,” he said, “I think Mr. Henderson can find other

markets for his literary wares, and more profitable ones.

I think,” he added, while the blood again rose in his cheeks,

“that I have some influence in certain literary quarters,

and I shall be happy to do all that I can to secure to him

that which he ought to receive for such careful work as

his. Your labor on the paper will not by any means take

up your whole power or time.”

“Well,” said Jim, “the fact is the same all the world over

—the people that grow a thing are those that get the

least for it. It isn't your farmers, that work early and late,

that get rich by what they raise out of the earth, it's the

middlemen and the hucksters. And just so it is in literature;

and the better a fellow writes, and the more work he

puts into it, the less he gets paid for it. Why, now, look

at me,” he said, “perching himself astride the arm of a

chair, “I'm a genuine literary humbug, but I'll bet you

I'll make more money than either of you, because, you see,

I've no modesty and no conscience. Confound it all, those

are luxuries that a poor fellow can't afford to keep. I'm

a sounding brass and a tinkling cymbal, but I'm just the sort

of fellow the world wants, and, hang it, they shall pay

me for being that sort of fellow. I mean to make it shell

out, and you see if I don't. I'll bet you, now, that I'd write

a book that you wouldn't, either of you, be hired to write,

and sell one hundred thousand copies of it, and put the

money in my pocket, marry the handsomest, richest, and

best educated girl in New York, while you are trudging on,

doing good, careful work, as you call it.”

“Remember us in your will,” said I.

“Oh, yes, I will,” he said. “I'll found an asylumfor decayed

authors of merit—a sort of literary `Hotel des Invalides.”'

We had a hearty laugh over this idea, and, on the whole,

our evening passed off very merrily. When I shook hands

with Bolton for the night, it was with a silent conviction of

an interior affinity between us.

It is a charming thing in one's rambles to come across a

tree, or a flower, or a fine bit of landscape that one can

think of afterward, and feel richer for their its in the

world. But it is more when one is in a strange place, to

come across a man that you feel thoroughly persuaded is,

somehow or other, morally and intellectually worth exploring.

Our lives tend to become so hopelessly commonplace,

and the human beings we meet are generally so much one

just like another, that the possibility of a new and peculiar

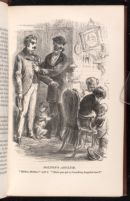

BOLTON'S ASYLUM.

"Halloo, Bolton!" said I. "Have you got a foundling hospital here?"

[Description: 467EAF. Image of Harry and Bolton standing in a living room looking down at three children huddled together by a fireplace. One child is sitting in a chair holding onto an infant while the other looks on. There is a small dog sitting on its hind legs begging Harry for a treat.]

one.

There was something about Bolton both stimulating and

winning, and I lay down less a stranger that night than I

had been since I came to New York.

| CHAPTER XIII.

BACHELOR COMRADES. My wife and I, or, Harry Henderson's history | ||