| CHAPTER V.

I START FOR COLLEGE AND MY UNCLE JACOB ADVISES ME. My wife and I, or, Harry Henderson's history | ||

5. CHAPTER V.

I START FOR COLLEGE AND MY UNCLE JACOB ADVISES ME.

THE time came at last when the sacred habit of intimacy

with my mother was broken, and I was

to leave her for college.

It was the more painful to her, as only a year before, my

father had died, leaving her more than ever dependent on

the society of her children.

My father died as he had lived, rejoicing in his work and

feeling that if he had a hundred lives to live, he would devote

them to the same object for which he had spent that

one—the preaching of the Gospel. He left to my mother the

homestead and a small farm, which was under the care of

one of my brothers, so that the event of his death made no

change in our family home center, and I was to go to college

and fulfill the hope of his heart and the desire of my

mother's life, in consecrating myself to the work of the

Christian ministry.

My father and mother had always kept sacredly a little

fund laid by for the education of their children; it was the

result of many small savings and self-denials—but self-denials

so cheerfully and hopefully encountered that they

had almost changed their nature and become preferences.

The family fund for this purpose had been used in turn by

two of my older brothers, who, as soon as they gained an

independent foothold in life, appropriated each his first

earnings to replacing this sum for the use of the next.

It was not, however, a fund large enough to dispense with

the need of a strict economy, and a supplemental self-helpfulness

on our part.

The terms in some of our New England colleges are

thoughtfully arranged so that the students can teach for

three of the winter months, and the resources thus gained

help out their college expenses. Thus at the same time they

educate themselves and help to educate others, and they

study with the maturity of mind and the appreciation of the

value of what they are gaining, resulting from a habit of

measuring themselves with the actual needs of life.

The time when the boy goes to college is the time when he

feels manhood to begin. He is no longer a boy, but an unfledged,

undeveloped man—a creature, half of the past and

half of the future. Yet every one gives him a good word

or a congratulatory shake of the hand on his entrance to

this new plateau of life. It is a time when advice is plenty

as blackberries in August, and often held quite as cheap—

but nevertheless a young fellow may as well look at what

his elders tell him at this time, and see what he can make

of it.

As I was “our minister's son,” all the village thought it

had something to do with my going. “Hallo, Harry, so

you've got into college! Think you'll be as smart a man as

your dad?” said one. “Wa-al, so I hear you're going to college.

Stick to it now. I could a made suthin ef I'd a had

larnin at your age,” said old Jerry Smith, who rung the

meeting-house bell, sawed wood, and took care of miscellaneous

gardens for sundry widows in the vicinity.

But the sayings that struck me as most to the purpose

came from my Uncle Jacob.

Uncle Jacob was my mother's brother, and the doctor not

only of our village, but of all the neighborhood for ten miles

round. He was a man celebrated for medical knowledge

through the State, and known by his articles in medical

journals far beyond. He might have easily commanded a

wider and more lucrative sphere of practice by going to

any of the large towns and cities, but Uncle Jacob was a

philosopher and preferred to live in a small quiet way in a

place whose scenery suited him, and where he could act

humors and pet ideas without rubbing against conventionalities.

He had a secret adoration for my mother, whom he regarded

as the top and crown of all womanhood, and he

also enjoyed the society of my father, using him as a sort of

whetstone to sharpen his wits on. Uncle Jacob was a

church member in good standing, but in the matter of belief

he was somewhat like a high-mettled horse in a pasture,—he

enjoyed once in a while having a free argumentative race

with my father all round the theological lot. Away he

would go in full career, dodging definitions, doubling and

turning with elastic dexterity, and sometimes ended by

leaping over all the fences, with most astounding assertions,

after which he would calm down, and gradually suffer

the theological saddle and bridle to be put on him and go

on with edifying paces, apparently much refreshed by his

metaphysical capers.

Uncle Jacob was reported to have a wonderful skill in the

healing craft. He compounded certain pills which were

stated to have most wonderful effects. He was accustomed

to exact that, in order fully to develop their medical properties,

they should be taken after a daily bath, and be followed

immediately by a brisk walk of a specific duration in the

open air. The steady use of these pills had been known to

make wonderful changes in the cases of confirmed invalids,

a fact which Uncle Jacob used to notice with a peculiar

twinkle in the corner of his eye. It was sometimes whispered

that the composition of them was neither more nor

less than simple white sugar with a flavor of some harmless

essence, but upon this subject my Uncle Jacob was impenetrable.

He used to say, with the afore-mentioned waggish

twinkle, that their preparation was his secret.

Uncle Jacob had always had a special favor for me, shown

after his own odd and original manner. He would take me

in his chaise with him when driving about his business, and

keep my mind on a perpetual stretch with his odd questions

shrewd keen quality to all that he said, that stimulated like

a mental tonic, and none the less so for a stinging flavor of

sarcasm and cynicism, that stirred up and provoked one's

self-esteem. Yet as Uncle Jacob was companionable and

loved a listener, I think he was none the less agreeable to

me for this slight touch of his claws. One likes to find

power of any kind—and he who shows that he can both

scratch and bite effectively, if he holds his talons in sheath,

comes in time to be regarded as a sort of benefactor for his

forbearance: and so, though I got many a shrewd mental

nip and gripe from my Uncle Jacob, I gave on the whole

more heed to his opinion than that of anybody else that I

knew.

From the time that I had been detected with my self-invented

manuscript, up to the period of my going to college,

the expression of my thoughts by writing had always

been a passion with me, and from year to year my mind had

been busy with its own creations, which it was a solace and

amusement for me to record.

Of course there was ever so much crabbed manuscript,

and no less confused, immature thought. I wrote poems,

essays, stories, tragedies, and comedies. I demonstrated

the immortality of the soul. I sustained the future immortality

of the souls of animals. I wrote sonnets and odes,

in whole or in part on almost everything that could be mentioned

in creation.

My mother advised me to make Uncle Jacob my literary

mentor, and the best of my productions were laid under his

eye.

“Poor trash!” he was wont to say, with his usual kindly

twinkle. “But there must be poor trash in the beginning.

We must all eat our peck of dirt, and learn to write sense

by writing nonsense.” Then he would pick out here and

there a line or expression which he assured me was “not

bad.” Now and then he condescended to tell me that for a

boy of my age, so and so was actually hopeful, and that I

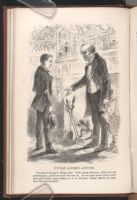

UNCLE JACOB'S ADVICE.

"So you are going to college, boy! Well, away with you; there's no use

advising you; you'll do as all the rest do. In one year you'll know more

than your father, your mother, or I, or all your college officers—in fact,

than the Lord himself."

[Description: 467EAF. Image of a young Harry having a solemn discussion with his Uncle Jacob. Both men are wearing suits and standing in front of a fireplace. On the wall behind the fireplace are various trinkets, such as a candle, ornate clock, an engraved bottle and a landscape portrait. On the wall is a bookshelf with books askew.]

more encouragement than much more decided praise from

any other quarter.

We all notice that he who is reluctant to praise, whose

commendation is scarce and hard-earned, is he for whose

good word everybody is fighting; he comes at last to be the

judge in the race. After all, the fact which Uncle Jacob

could not disguise, that he had a certain good opinion of

me, in spite of his sharp criticisms and scant praises, made

him the one whose dicta on every subject were the most important

to me.

I went to him in all the glow of satisfaction and the tremble

of self-importance that a boy feels who is taking the

first step into the land of manhood.

I have the image of him now, as he stood with his back to

the fire, and the newspaper in his hand, giving me his last

counsels. A little wiry, keen-looking man, with a blue,

hawk-like eye, a hooked nose, a high forehead, shadowed

with grizzled hair, and a cris-cross of deeply lined wrinkles

in his face.

“So you are going to college, boy! Well, away with you;

there 's no use advising you; you 'll do as all the rest do. In

one year you'll know more than your father, your mother,

or I, or all your college officers—in fact, than the Lord himself.

You'll have doubts about the Bible, and think you

could have made a better one. You 'll think that if the

Lord had consulted you he could have laid the foundations

of the earth better, and arranged the course of nature to

more purpose. In short, you'll be a god, knowing good and

evil, and running all over creation measuring everybody

and everything in your pint cup. There'll be no living with

you. But you'll get over it,—it's only the febrile stage of

knowledge. But if you have a good constitution, you'll

come through with it.”

I humbly suggested to him that I should try to keep clear

of the febrile stage; that forewarned was forearmed.

“Oh, tut! tut! you must go through your fooleries. These

mumps of young manhood; you 'll have them all. We only

pray that you may have them light, and not break your constitution

for all your life through, by them. For instance,

you'll fall in love with some baby-faced young thing, with

pink cheeks and long eyelashes, and goodness only knows

what abominations of sonnets you'll be guilty of. That

isn't fatal, however. Only don't get engaged. Take it as

the chicken-pox—keep your pores open, and don't get cold,

and it'll pass off and leave you none the worse.”

“And she!” said I, indignantly. “You talk as if it was

no matter what became of her—”

“What, the baby? Oh, she'll outgrow it, too. The fact

is, soberly and seriously, Harry, marriage is the thing that

makes or mars a man; it's the gate through which he goes

up or down, and you shouldn't pledge yourself to it till you

come to your full senses. Look at your mother, boy; see

what a woman may be; see what she was to your father,

what she is to me, to you, to every one that knows her.

Such a woman, to speak reverently, is a pearl of great

price; a man might well sell all he had to buy her. But it

isn't that kind of woman that flirts with college boys. You

don't pick up such pearls every day.”

Of course I declared that nothing was further from my

thoughts than anything of that nature.

“The fact is, Harry, you can't afford fooleries,” said my

uncle. “You have your own way to make, and nothing to

make it with but your own head and hands, and you must

begin now to count the cost of everything. You have a

healthy, sound body; see that you take care of it. God gives

you a body but once. He don't take care of it for you,

and whatever of it you lose, you lose for good. Many a

chap goes into college fresh as you are, and comes out with

weak eyes and crooked back, yellow complexion and dyspeptic

stomach. He has only himself to thank for it. When

you get to college they'll want you to smoke, and you'll

want to, just for idleness and good fellowship. Now, before

get a good cigar under ten cents, and your smoker wants

three a day, at the least. There go thirty cents a day, two

dollars and ten cents a week, or a hundred and nine dollars

and twenty cents a year. Take the next ten years at that

rate, and you can invest over a thousand dollars in tobacco

smoke. That thousand dollars, invested in a savings bank,

would give a permanent income of sixty dollars a year,—

a handy thing, as you'll find, just as you are beginning life.

Now, I know you think all this is prosy; You are amazingly

given to figures of rhetoric, but, after all, you've got to get

on in a world where things go by the rules of arithmetic.”

“Well, uncle,” I said, a little nettled, “I pledge you my

word that I won't smoke or drink. I never have done

either, and I don't know why I should.”

“Good for you! your hand on that, my boy. You don't

need either tobacco or spirits any more than you need water

in your shoes. There's no danger in doing without them,

and great danger in doing with them; so let's look on that

as settled.

“Now, as to the rest. You have a faculty for stringing

words together, and a hankering after it, that may make or

spoil you. Many a fellow comes to naught because he can

string pretty phrases and turn a good line of poetry. He

gets the notion that he's to be a poet, or orator, or genius of

some sort, and neglects study. Now, Harry, remember that

an empty bag can't stand upright; and that if you are ever

to be a writer you must have something to say, and that

you've got to dig for knowledge as for hidden treasure.

A genius for hard work is the best kind of genius. Look at

great writers, and see how many had it. What a student

Milton was, and Goethe! Great fellows, those!—like trees

that grow out in a pasture lot, with branches all round.

Composition is the flowering out of a man's mind. When

he has made growth, all studies and all learning, all that

makes woody fibre, go into it. Now, study books; observe

nature; practice. If you make a good firm mental growth,

days. So go your ways, and God bless you!”

The last words were said as Uncle Jacob slipped into my

hand an envelope, containing a sum of money. “You'll

need it,” he said, “to furnish your room; and hark'e! if

you get into any troubles that you don't want to burden

your mother with, come to me.”

There was warmth in the grip with which these last

words were said, and a sort of misty moisture came over

his keen blue eye,—little signs which meant as much from

his shrewd and reticent nature as a caress or an expression

of tenderness might from another.

My mother's last words, after hours of talk over the evening

fire, were these: “I want you to be a good man. A

great many have tried to be great men, and failed; but

nobody ever sincerely tried to be a good man, and failed.”

I suppose it is about the happiest era in a young fellow's

life, when he goes to college for the first time.

The future is all a land of blue distant mists and shadows,

radiant as an Italian landscape. The boundaries between

the possible and the not possible are so charmingly vague!

There is a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow forever

waiting for each new comer. Generations have not exhausted

it!

De Balzac said, of writing his novels, that the dreaming

out of them was altogether the best of it. “To imagine,”

he said, “is to smoke enchanted cigarettes; to bring out

one's imaginations into words,—that is work!”

The same may be said of the romance of one's life. The

dream-life is beautiful, but the rendering into reality quite

another thing.

I believe every boy who has a good father and mother,

goes to college meaning, in a general way, to be a good fellow.

He will not disappoint them.—No! a thousand times,

no! In the main, he will be a good boy,—not that he is

going quite to walk according to the counsels of his elders.

He is not going to fall over any precipices—not he—but

of them, and take a dispassionate survey of the prospect,

and gather a few botanical specimens here and there. It

might be dangerous for a less steady head than his; but he

understands himself, and with regard to all things he says,

“We shall see.” The world is full of possibilities and open

questions. Up sail, and away; let us test them!

As I scaled the mountains and descended the valleys on

my way to college, I thought over all that my mother and

Uncle Jacob had said to me, and had my own opinion of it.

Of course I was not the person to err in the ways he had

suggested. I was not to be the dupe of a boy and girl flirtation.

My standard of manhood was too exalted, I reflected,

and I thought with complacency how little Uncle

Jacob knew of me.

To be sure, it is a curious kind of a thought to a young

man, that somewhere in this world, unknown to him, and

as yet unknowing him, lives the woman that is to be his

earthly fate,—to affect, for good or evil, his destiny.

We have all read the pretty story about the Princess of

China and the young Prince of Tartary, whom a fairy and

genius in a freak of caprice showed to each other in an enchanted

sleep, and then whisked away again, leaving them

to years of vain pursuit and wanderings. Such is the ideal

image of somebody, who must exist somewhere, and is to be

found sometime, and when found, is to be ours.

“Uncle Jacob is all right in the main,” I said; “but if I

should meet the true woman even in my college days, why

that, indeed, would be quite another thing.”

| CHAPTER V.

I START FOR COLLEGE AND MY UNCLE JACOB ADVISES ME. My wife and I, or, Harry Henderson's history | ||