Wearing of the gray being personal portraits, scenes and adventures of the war |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. | XI.

JACKSON'S DEATH-WOUND. |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 12. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| Wearing of the gray | ||

XI.

JACKSON'S DEATH-WOUND.

1. I.

There is an event of the late war, the details of which are

known only to a few persons; and yet it is no exaggeration to

say that many thousands would feel an interest in the particulars.

I mean the death of Jackson. The minute circumstances

attending it have never been published, and they are here

recorded as matter of historical as well as personal interest.

A few words will describe the situation of affairs when this

tragic scene took place. The spring of 1862 saw a large Federal

army assembled on the north bank of the Rappahannock, and on

the first of May, General Hooker, its commander, had crossed,

and firmly established himself at Chancellorsville. General

Lee's forces were opposite Fredericksburg chiefly, a small body

of infantry only watching the upper fords. This latter was

compelled to fall back before General Hooker's army of about

one hundred and fifty thousand men, and Lee bastened by forced

marches from Fredericksburg toward Chancellorsville, with a

force of about thirty thousand men—Longstreet being absent at

Suffolk—to check the further advance of the enemy. This was

on May 1st, and the Confederate advance force under Jackson,

on the same evening, attacked General Hooker's intrenchments

facing toward Fredericksburg. They were found impregnable,

the dense thickets having been converted into abattis, and every

avenue of approach defended with artillery. General Lee therefore

directed the assault to cease, and consulted with his corps

movement around the Federal front, and a determined attack

upon the right flank of General Hooker, west of Chancellorsville.

The ground on his left and in his front gave such enormous

advantages to the Federal troops that an assault there was

impossible, and the result of the consultation was the adoption

of Jackson's suggestion to attack the enemy's right. Every

preparation was made that night, and on the morning of May

second, Jackson set out with Hill's, Rodes's, and Colston's divisions,

in all about twenty-two thousand men, to accomplish his

undertaking.

Chancellorsville was a single brick house of large dimensions,

situated on the plank-road from Fredericksburg to Orange, and

all around it were the thickets of the country known as the

Wilderness. In this tangled undergrowth the Federal works

had been thrown up, and such was the denseness of the woods

that a column moving a mile or two to the south was not apt to

be seen. Jackson calculated upon this, but fortune seemed

against him. At the Catherine Furnace, a mile or two from the

Federal line, his march was discovered, and a hot attack was

made on his rear-guard as he moved past. All seemed now discovered,

but, strange to say, such was not the fact. The Federal

officers saw him plainly, but the winding road which he pursued

chanced here to bend toward the south, and it was afterward

discovered that General Hooker supposed him to be in full

retreat upon Richmond. Such at least was the statement of Federal

officers. Jackson repulsed the attack upon his rear, continued

his march, and striking into what is called the Brock

Road, turned the head of his column northward, and rapidly

advanced around General Hooker's right flank. A cavalry force

under General Stuart had moved in front and on the flanks of

the column, driving off scouting parties and other too inquisitive

wayfarers; and on reaching the junction of the Orange and

Germanna roads a heavy Federal picket was forced to retire.

General Fitz Lee then informed Jackson that from a hill near at

hand he could obtain a view of the Federal works, and proceeding

thither, Jackson reconnoitred. This reconnoissance showed

an aide, “Tell my column to cross that road,” pointing to the

plank-road. His object was to reach the “old turnpike,” which

ran straight down into the Federal right flank. It was reached

at about five in the evening, and without a moment's delay

Jackson formed his line of battle for an attack. Rodes's division

moved in front, supported at an interval of two hundred yards

by Colston's, and behind these A. P. Hill's division marched in

column like the artillery, on account of the almost impenetrable

character of the thickets on each side of the road.

Jackson's assault was sudden and terrible. It struck the

Eleventh corps, commanded on this occasion by General Howard,

and, completely surprised, they retreated in confusion upon

the heavy works around Chancellorsville. Rodes and Colston

followed them, took possession of the breastworks across the

road, and a little after eight o'clock the Confederate troops were

within less than a mile of Chancellorsville, preparing for a new

and more determined attack. Jackson's plan was worthy of being

the last military project conceived by that resolute and enterprising

intellect. He designed putting his entire force into action,

extending his left, and placing that wing between General

Hooker and the Rappahannock. Then, unless the Federal commander

could cut his way through, his army would be captured

or destroyed. Jackson commenced the execution of this plan

with vigour, and an obvious determination to strain every nerve,

and incur every hazard to accomplish so decisive a success.

Rodes and Colston were directed to retire a short distance, and

re-form their lines, now greatly mingled, and Hill was ordered

to move to the front and take their places. On fire with his

great design, Jackson then rode forward in front of the troops

toward Chancellorsville, and here and then the bullet struck him

which was to terminate his career.

The details which follow are given on the authority of Jackson's

staff officers, and one or two others who witnessed all that

occurred. In relation to the most tragic portion of the scene,

there remained, as will be seen, but a single witness.

Jackson had ridden forward on the turnpike to reconnoitre,

the position of the Federal lines. The moon shone, but it was

struggling with a bank of clouds, and afforded but a dim light.

From the gloomy thickets on each side of the turnpike, looking

more weird and sombre in the half light, came the melancholy

notes of the whippoorwill. “I think there must have been ten

thousand,” said General Stuart afterwards. Such was the scene

amid which the events now about to be narrated took place.

Jackson had advanced with some members of his staff, considerably

beyond the building known as “Melzi Chancellor's,”

about a mile from Chancellorsville, and had reached a point

nearly opposite an old dismantled house in the woods near the

road, whose shell-torn roof may still be seen, when he reined in

his horse, and remaining perfectly quiet and motionless, listened

intently for any indications of a movement in the Federal lines.

They were scarcely two hundred yards in front of him, and seeing

the danger to which he exposed himself one of his staff officers

said, “General, don't you think this is the wrong place for

you?” He replied quickly, almost impatiently, “The danger is

all over! the enemy is routed—go back and tell A. P. Hill to

press right on!” The officer obeyed, but had scarcely disappeared

when a sudden volley was fired from the Confederate

infantry in Jackson's rear, and on the right of the road—evidently

directed upon him and his escort. The origin of this fire

has never been discovered, and after Jackson's death there was

little disposition to investigate an occurrence which occasioned

bitter distress to all who by any possibility could have taken

part in it. It is probable, however, that some movement of the

Federal skirmishers had provoked the fire; if this is an error,

the troops fired deliberately upon Jackson and his party, under

the impression that they were a body of Federal cavalry reconnoitring.

It is said that the men had orders to open upon any

object in front, “especially upon cavalry;” and the absence of

pickets or advance force of any kind on the Confederate side

explains the rest. The enemy were almost in contact with them;

the Federal artillery, fully commanding the position of the troops,

was expected to open every moment; and the men were just in

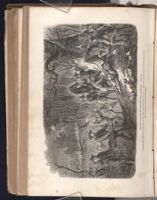

DEATH WOUND OF STONEWALL JACKSON.—Page 301.

“He was then carried to the side of the road, and laid under a tree.” His last words were, “Let us cross over

the river and rest under the shade.”

[Description: 521EAF. Illustration page, which depicts the death of Stonewall Jackson. He is shown lying under a large tree, dying, as groups of Confederate soldiers gather around. The background image is filled with Confederate soldiers running towards Jackson, some with swords aloft and one with flag raised and waving.]

every object they see.

Whatever may have been the origin of this volley, it came,

and many of the staff and escort were shot, and fell from their

horses. Jackson wheeled to the left and galloped into the woods

to get out of range of the bullets; but he had not gone twenty

steps beyond the edge of the turnpike, in the thicket, when one

of his brigades drawn up within thirty yards of him fired a volley

in their turn, kneeling on the right knee, as the flash of the

guns showed, as though prepared to “guard against cavalry.”

By this fire Jackson was wounded in three places. He received

one ball in his left arm, two inches below the shoulder-joint, shattering

the bone and severing the chief artery; a second passed

through the same arm between the elbow and the wrist, making

its exit through the palm of the hand; and a third ball entered

the palm of his right hand, about the middle, and passing through

broke two of the bones. At the moment when he was struck,

he was holding his rein in his left hand, and his right was raised

either in the singular gesture habitual to him, at times of excitement,

or to protect his face from the boughs of the trees. His

left hand immediately dropped at his side, and his horse, no

longer controlled by the rein, and frightened at the firing,

wheeled suddenly and ran from the fire in the direction of the

Federal lines. Jackson's helpless condition now exposed him

to a distressing accident. His horse darted violently between

two trees, from one of which a horizontal bough extended,

at about the height of his head, to the other; and as he passed

between the trees, this bough struck him in the face, tore off his

cap, and threw him violently back on his horse. The blow was

so violent as nearly to unseat him, but it did not do so, and

rising erect again, he caught the bridle with the broken and

bleeding fingers of his right hand, and succeeded in turning his

horse back into the turnpike. Here Captain Wilbourn, of his

staff, succeeded in catching the reins and checking the animal,

who was almost frantic from terror, at the moment when, from

loss of blood and exhaustion, Jackson was about to fall from the

saddle.

The scene at this time was gloomy and depressing. Horses

mad with fright at the close firing were seen running in every

direction, some of them riderless, others defying control; and

in the wood lay many wounded and dying men. Jackson's

whole party, except Captain Wilbourn and a member of the

signal corps, had been killed, wounded, or dispersed. The man

riding just behind Jackson had had his horse killed; a courier

near was wounded and his horse ran into the Federal lines;

Lieutenant Morrison, aide-de-camp, threw himself from the saddle,

and his horse fell dead a moment afterwards; Captain Howard

was wounded and carried by his horse into the Federal camps;

Captain Leigh had his horse shot under him; Captain Forbes

was killed; and Captain Boswell, Jackson's chief engineer, was

shot through the heart, and his dead body carried by his frightened

horse into the lines of the enemy near at hand.

2. II.

Such was the fatal result of this causeless fire. It had ceased

as suddenly as it began, and the position in the road which

Jackson now occupied was the same from which he had been

driven. Captain Wilbourn, who with Mr. Wynn, of the signal

corps, was all that was left of the party, notices a singular circumstance

which attracted his attention at this moment. The

turnpike was utterly deserted with the exception of himself, his

companion, and Jackson; but in the skirting of thicket on the

left he observed some one sitting on his horse, by the side of the

road, and coolly looking on, motionless and silent. The unknown

individual was clad in a dark dress which strongly resembled

the Federal uniform; but it seemed impossible that one

of the enemy could have penetrated to that spot without being

discovered, and what followed seemed to prove that he belonged

to the Confederates. Captain Wilbourn directed him to “ride

up there and see what troops those were”—the men who had

fired on Jackson—when the stranger slowly rode in the direction

was, is left to conjecture.

Captain Wilbourn, who was standing by Jackson, now said,

“They certainly must be our troops,” to which the General assented

with a nod of the head, but said nothing. He was looking

up the road toward his lines with apparent astonishment,

and continued for some time to look in that direction as if unable

to realize that he could have been fired upon and wounded by

his own men. His wound was bleeding profusely, the blood

streaming down so as to fill his gauntlets, and it was necessary

to secure assistance promptly. Captain Wilbourn asked him if

he was much injured, and urged him to make an effort to move

his fingers, as his ability to do this would prove that his arm was

not broken. He endeavoured to do so, looking down at his

hand during the attempt, but speedily gave it up, announcing

that his arm was broken. An effort which his companion made

to straighten it caused him great pain, and murmuring, “You

had better take me down,” he leaned forward and fell into Captain

Wilbourn's arms. He was so much exhausted by loss of

blood that he was unable to take his feet out of the stirrups, and

this was done by Mr. Wynn. He was then carried to the side

of the road and laid under a small tree, where Captain Wilbourn

supported his head while his companion went for a surgeon and

ambulance to carry him to the rear, receiving strict instructions,

however, not to mention the occurrence to any one but Dr.

McGuire, or other surgeon. Captain Wilbourn then made an

examination of the General's wounds. Removing his field-glasses

and haversack, which latter contained some paper and

envelopes for dispatches, and two religious tracts, he put these

on his own person for safety, and with a small pen-knife proceeded

to cut away the sleeves of the india-rubber overall, dresscoat,

and two shirts, from the bleeding arm.

While this duty was being performed, General Hill rode up

with his staff, and dismounting beside the general expressed his

great regret at the accident. To the question whether his wound

was painful, Jackson replied, “Very painful,” and added that

“his arm was broken.” General Hill pulled off his gauntlets,

He then seemed easier, and having swallowed a mouthful

of whiskey, which was held to his lips, appeared much refreshed.

It seemed impossible to move him without making his

wounds bleed afresh, but it was absolutely necessary to do so,

as the enemy were not more than a hundred and fifty yards distant,

and might advance at any moment—and all at once a proof

was given of the dangerous position which he occupied. Captain

Adams, of General Hill's staff, had ridden ten or fifteen

yards ahead of the group, and was now heard calling out, “Halt!

surrender! fire on them if they don't surrender!” At the next

moment he came up with two Federal skirmishers who had at

once surrendered, with an air of astonishment, declaring that

they were not aware they were in the Confederate lines.

General Hill had drawn his pistol and mounted his horse;

and he now returned to take command of his line and advance,

promising Jackson to keep his accident from the knowledge of

the troops, for which the general thanked him. He had scarcely

gone when Lieutenant Morrison, who had come up, reported the

Federal line advancing rapidly, and then within about a hundred

yards of the spot, and exclaimed: “Let us take the General up

in our arms and carry him off.” But Jackson said faintly, “No,

if you can help me up, I can walk.” He was accordingly lifted

up and placed upon his feet, when the Federal batteries in front

opened with great violence, and Captain Leigh, who had just

arrived with a litter, had his horse killed under him by a shell.

He leaped to the ground, near Jackson, and the latter leaning

his right arm on Captain Leigh's shoulder, slowly dragged himself

along toward the Confederate lines, the blood from his

wounded arm flowing profusely over Captain Leigh's uniform.

Hill's lines were now in motion to meet the coming attack,

and as the men passed Jackson, they saw from the number and

rank of his escort that he must be a superior officer. “Who is

that—who have you there?” was asked, to which the reply was,

“Oh! it's only a friend of ours who is wounded.” These inquiries

became at last so frequent that Jackson said to his escort:

“When asked, just say it is a Confederate officer.”

It was with the utmost difficulty that the curiosity of the

troops was evaded. They seemed to suspect something, and

would go around the horses which were led along on each side

of the General to conceal him, to see if they could discover who

it was. At last one of them caught a glimpse of the general,

who had lost his cap, as we have seen, in the woods, and was

walking bareheaded in the moonlight—and suddenly the man

exclaimed “in the most pitiful tone,” says an eye-witness:

“Great God! that is General Jackson!” An evasive reply was

made, implying that this was a mistake, and the man looked

from the speaker to Jackson with a bewildered air, but passed

on without further comment. All this occurred before Jackson

had been able to drag himself more than twenty steps; but

Captain Leigh had the litter at hand, and his strength being

completely exhausted, the General was placed upon it, and borne

toward the rear.

The litter was carried by two officers and two men, the rest

of the escort walking beside it and leading the horses. They

had scarcely begun to move, however, when the Federal artillery

opened a furious fire upon the turnpike from the works in

front of Chancellorsville, and a hurricane of shell and canister

swept the road. What the eye then saw was a scene of disordered

troops, riderless horses, and utter confusion. The intended

advance of the Confederates had doubtless been discovered, and

the Federal fire was directed along the road over which they

would move. By this fire Generals Hill and Pender, with several

of their staff, were wounded, and one of the men carrying

the litter was shot through both arms and dropped his burden.

His companion did likewise, hastily flying from the dangerous

locality, and but for Captain Leigh, who caught the handle of

the litter, it would have fallen to the ground. Lieutenant Smith

had been leading his own and the General's horse, but the animals

now broke away, in uncontrollable terror, and the rest of

the party scattered to find shelter. Under these circumstances

the litter was lowered by Captain Leigh and Lieutenant Smith

into the road, and those officers lay down by it to protect themselves,

in some degree, from the heavy fire of artillery which

flinty stones of the roadside.” Jackson raised himself upon his

elbow and attempted to get up, but Lieutenant Smith threw his

arm across his breast and compelled him to desist. They lay in

this manner for some minutes without moving, the hurricane

still sweeping over them. “So far as I could see,” wrote one of

the officers, “men and horses were struggling with a most terrible

death.” The road was, otherwise, deserted. Jackson and

his two officers were the sole living occupants of the spot.

The fire of canister soon relaxed, though that of shot and

shell continued; and Jackson rose to his feet. Leaning on the

shoulders of the party who had rejoined him, he turned aside

from the road, which was again filling with infantry, and struck

into the woods—one of the officers following with the litter.

Here he moved with difficulty among the troops who were lying

down in line of battle, and the party encountered General Pender,

who had just been slightly wounded. He asked who it was

that was wounded, and the reply was, “A Confederate officer.”

General Pender, however, recognised Jackson, and exclaimed:

“Ah! General, I am sorry to see you have been wounded. The

lines here are so much broken that I fear we will have to fall

back.” These words seemed to affect Jackson strongly. He

raised his head, and said with a flash of the eye, “You must

hold your ground, General Pender! you must hold your ground,

sir!” This was the last order Jackson ever gave upon the

field.

3. III.

The General's strength was now completely exhausted, and he

asked to be permitted to lie down upon the ground. But to

this the officers would not consent. The hot fire of artillery

which still continued, and the expected advance of the Federal

infantry, made it necessary to move on, and the litter was again

put in requisition. The General, now nearly fainting, was laid

upon it, and some litter-bearers having been procured, the whole

Melzi Chancellor's.

So dense was the undergrowth, and the ground so difficult,

that their progress was very slow. An accident now occasioned

Jackson untold agony. One of the men caught his foot in a

vine, and stumbling, let go the handle of the litter, which fell

heavily to the ground. Jackson fell upon his left shoulder,

where the bone had been shattered, and his agony must have

been extreme. “For the first time,” says one of the party, “he

groaned, and that most piteously.” He was quickly raised, however,

and a beam of moonlight passing through the foliage overhead,

revealed his pale face, closed eyes, and bleeding breast.

Those around him thought that he was dying. What a death

for such a man! All around him was the tangled wood, only

half illumined by the struggling moonbeams; above him burst

the shells of the enemy, exploding, says an officer, “like showers

of falling stars,” and in the pauses came the melancholy notes

of the whippoorwills, borne on the night air. In this strange

wilderness, the man of Port Republic and Manassas, who had

led so many desperate charges, seemed about to close his eyes

and die in the night.

But such was not to be the result then. When asked by one

of the officers whether he was much hurt, he opened his eyes

and said quietly without further exhibition of pain, “No, my

friend, don't trouble yourself about me.” The litter was then

raised upon the shoulders of the men, the party continued their

way, and reaching an ambulance near Melzi Chancellor's placed

the wounded General in it. He was then borne to the field hospital

at Wilderness Run, some five miles distant.

Here he lay throughout the next day, Sunday, listening to

the thunder of the artillery and the long roll of the musketry

from Chancellorsville, where Stuart, who had succeeded him in

command, was pressing General Hooker back toward the Rappahannock.

His soul must have thrilled at that sound, long so

familiar, but he could take no part in the conflict. Lying faint

and pale, in a tent in rear of the “Wilderness Tavern,” he

seemed to be perfectly resigned, and submitted to the painful

necessary to amputate the arm, and one of his surgeons asked,

“If we find amputation necessary, General, shall it be done at

once?” to which he replied with alacrity, “Yes, certainly, Dr.

McGuire, do for me whatever you think right.” The arm was

then taken off, and he slept soundly after the operation, and on

waking, began to converse about the battle. “If I had not

been wounded,” he said, “or had had one hour more of daylight,

I would have cut off the enemy from the road to United States

ford; we would have had them entirely surrounded, and they

would have been obliged to surrender or cut their way out; they

had no other alternative. My troops may sometimes fail in

driving an enemy from a position, but the enemy always fails to

drive my men from a position.” It was about this time that we

received the following letter from General Lee: “I have just

received your note informing me that you were wounded. I

cannot express my regret at the occurrence. Could I have directed

events I should have chosen for the good of the country

to have been disabled in your stead. I congratulate you upon

the victory which is due to your skill and energy.”

The remaining details of Jackson's illness and death are

known. He was removed to Guinney's Depot, on the Richmond

and Fredericksburg Railroad, where he gradually sank, pneumonia

having attacked him. When told that his men on Sunday

had advanced upon the enemy shouting “Charge, and remember

Jackson!” he exclaimed, “It was just like them! it

was just like them! They are a noble body of men! The

men who live through this war,” he added, “will be proud to

say `I was one of the Stonewall brigade' to their children.”

Looking soon afterwards at the stump of his arm, he said,

“Many people would regard this as a great misfortune. I regard

it as one of the great blessings of my life.” He subsequently

said, “I consider these wounds a blessing; they were

given me for some good and wise purpose, and I would not part

with them if I could.”

His wife was now with him, and when she announced to him,

weeping, his approaching death, he replied with perfect calmness,

last words. He soon afterwards became delirious, and was heard

to mutter “Order A. P. Hill to prepare for action!—Pass the

infantry to the front!—Tell Major Hawks to send forward provisions

for the men!” Then his martial ardor disappeared, a

smile diffused itself over his pale features, and he murmured:

“Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the

trees!” It was the river of death he was about to pass; and

soon after uttering these words, he expired.

Such were the circumstances attending the death-wound of

Jackson. I have detailed them with the conciseness—but the

accuracy, too—of a procès-verbal. The bare statement is all that

is necessary—comment may be spared the reader.

The character and career of the man who thus passed from

the arena of his glory, are the property of history.

| Wearing of the gray | ||